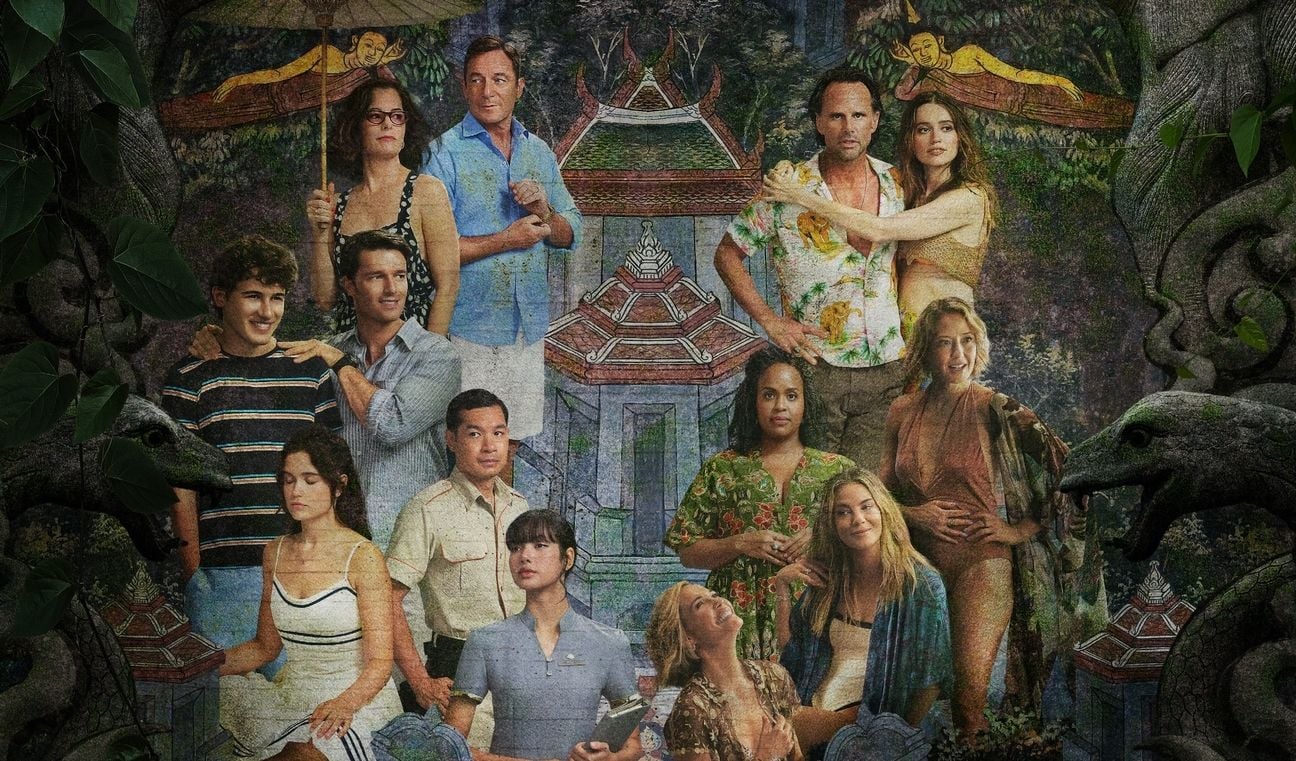

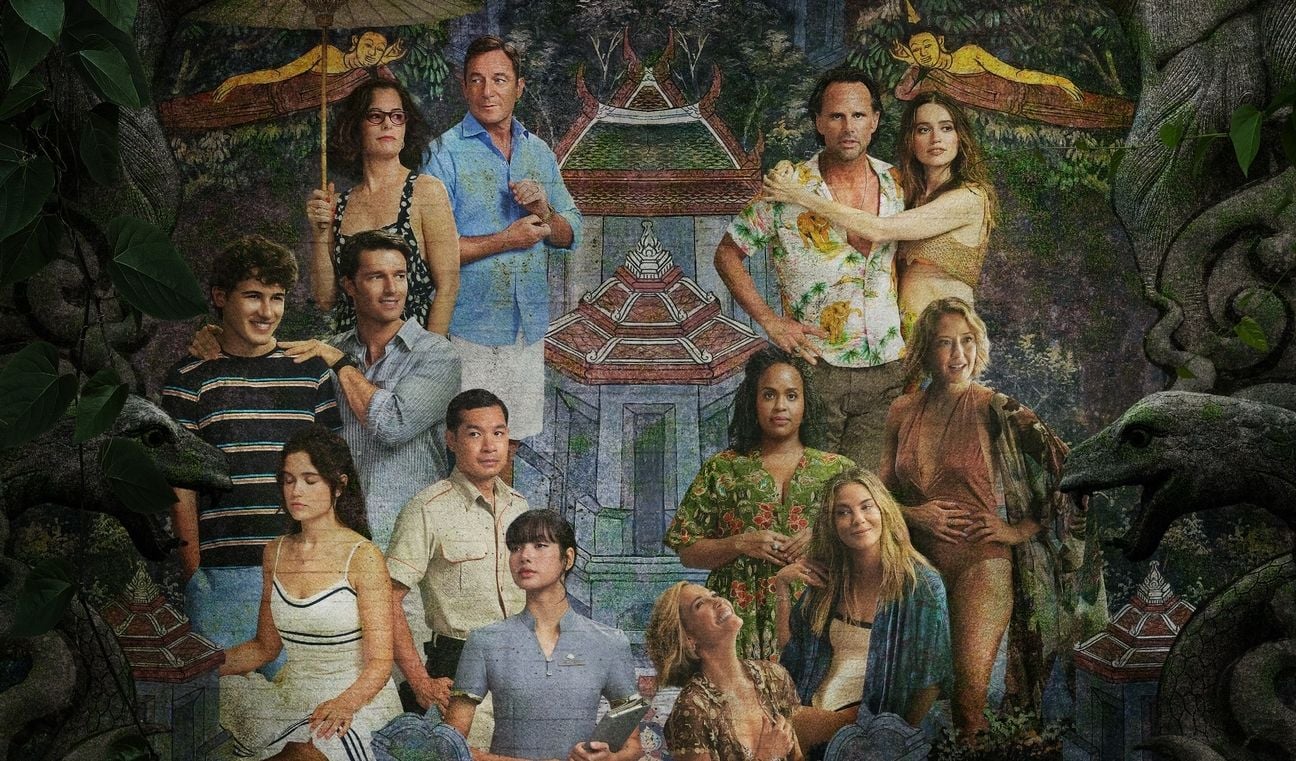

Problematic luxury resorts, obnoxious tourists and the catchiest theme song in the history of television. I am utterly obsessed with HBO’s social satire The White Lotus. It seems there is something perversely seductive about watching the morally bankrupt go on holiday.

For the uninitiated, each series of The White Lotus is set in a different hotel of the fictional, eponymous resort chain. The show is a sharp dissection of wealth and power dynamics, with an ensemble cast who play multi-faceted, but largely awful people. Even those who initially come across as sympathetic usually end up embodying some heinous facet of modern society - be it white privilege, generational chauvinism or colonial ignorance. There is a dead body at the start of each series and it says a lot that the death is irrelevant to the bulk of the plot, which instead is driven more by narcissism and ego than murder mystery.

The true tension of The White Lotus lies between critique and allure.

Without sacrificing entertainment, the first season of The White Lotus, set in Hawaii, hooked audiences with a showcase of key issues so often overlooked in tourism - the leakage that means locals too often don’t see the financial benefits of tourism, and the dilution of cultures for visitor consumption.

There is one point, though, that fascinates me. This TV show presents tourism at its warts-and-all worst and yet, at the end of each series, the location where the show was shot consistently sees a substantial boost in travel demand.

Season one led to a 386% increase in availability checks for the Four Seasons Maui in Hawaii. Taormina, the Sicilian town at the centre of season two, saw properties booked out for months, and just the trailer for season three alone - which is set in Thailand - sparked a 412% increase in search for Thai holidays.

Here lies The White Lotus paradox.

Showrunner Mike White’s masterpiece presents paradise as a purgatory of entitlement and exploitation. So between the death, drugs and desecration, why does watching awful tourists make us want to follow in their footsteps?

Let’s start with the obvious. Regardless of how horrid the characters are, the settings are gorgeous. The rolling hills of Sicily, the golden beaches of Maui and the waters of Thailand all exist beyond the moral failings of their visitors. Their beauty is indifferent to who walks through them, and so, they feel recoverable.

The cinematography is seductive, showing us pure, natural beauty in amongst narratives centred on desire. Even as the show critiques the indulgences of the ultra-rich, it can't help but frame the settings as intoxicatingly desirable. We laugh at the hubris, but we want that Aperol Spritz overlooking the Ionian Sea.

The rolling hills of Sicily, the golden beaches of Maui and the waters of Thailand all exist beyond the moral failings of their visitors...

Will Sharpe’s character Ethan brings up ‘mimetic theory’ during a conversation in season two - “if someone with higher status than you wants something, it means it’s more likely you’ll want it too.” René Girard, the French philosopher who originally developed that idea, argued that desire is not created in a vacuum.

The idea of seeing others indulging makes us want to do so too.

In The White Lotus, desire operates on multiple levels. Guests mimic each other’s aspirations, whether that’s social status, romantic entanglements, power struggles (often fuelled by finance), and we, as viewers, become ensnared in this mimetic loop as well. We see their desire, their pleasure, their excess, and even as we critique it, we internalise it. The show invites us to recoil from these characters while drawing us into the settings that enable the indulgence.

Luxury resorts are, themselves, often a contradiction. They market themselves as untouched paradises while requiring significant intervention, economic, environmental and cultural, to maintain the illusion. The White Lotus exposes this hypocrisy, yet it never fully erases the seduction of place.

The irony is that even as we tell ourselves we would behave better than the show’s characters, we are still drawn by the same impulses - desire, imitation, beauty...

It is, as Vogue recently stated, “an open secret” that The White Lotus always centres on a Four Seasons hotel, so it is interesting that it’s only now (with the show entering season three and cult-status firmly secured) that Four Seasons are formally capitalising on that relationship. The hotel chain is preparing to roll out “special beverage programs and/or spa treatments”, Vogue writes, tied to the show. It is comically meta, but also noteworthy that the Four Seasons decided it was best to wait to see how viewers would react to such awful tourist behaviour in their resorts before owning it. Turns out, it makes us want to travel.

The true tension of The White Lotus lies between critique and allure.

The show presents tourism as an industry built on exploitation, from underpaid local workers to cultural appropriation repackaged as 'experience', but it also never diminishes the fantasy. Instead, it sharpens it.

The camera lingers on lush jungles, infinity pools and the light of golden hour.

We know the politics are fraught, but our senses are still seduced. If we see a character basking in beauty, even if they are up to no good, we still absorb their pleasure. We still want to be there.

If The White Lotus inspires us to travel, it should also inspire us to interrogate how we do so.

When Kekoa Scott Kekumano's character Kai, a resort worker in season one, reveals that the hotel he works for was built on the ancestral land of indigenous people, it becomes a clear symbol of colonial displacement. But that doesn’t negate the beauty of a breaching whale viewed from a sandy beach later in the series.

The resort here is a sanitised, guest-friendly version of local culture; a stage. Guests are blissfully ignorant of the real world beyond, or simply indifferent.

The show serves as a warning against passive tourism, against travel places as personal playgrounds or ‘destinations’ rather than living, breathing places - showing us American characters searching for The Godfather in a romanticised Sicily, which encourages locals to caricature their 'Italian-ness' for financial gain, or focusing on the appropriation question around eastern faith, often ignored.

The critique is of how tourism turns real places into commodified spectacles, but the rise of 'White Lotus tourism' shows this critique itself can become a spectacle that also drives tourism. What follows may be a recursive loop where the tourism driven by the critique, ironically, exacerbates the problems being critiqued - each layer adding to rather than diminishing the place's allure and Disneyfication. It's what Guy Debord would call 'the spectacle of the anti-spectacle'.

Key to the The White Lotus paradox is our certainty that we will travel better.

We wouldn’t have drug-fuelled orgies with sex workers. We wouldn’t steal that arancini. Nobody would die - a low bar, admittedly, but a good start.

The show’s roster of smug tech bros, adulterous husbands and vapid socialites forms an unflattering mirror, but one we view with just enough distance to assure ourselves that we wouldn’t be so bad. We’d tip better, we tell ourselves. We’d be polite to the staff. We’d tread lightly, conscious of our impact. Watching them fumble through their vacations, oblivious to the real histories and cultures surrounding them, reinforces our belief in our own ethical superiority.

The White Lotus is a scathing criticism of tourism, but it's not anti-travel; it’s an invitation to hold a mirror up to widely-accepted travel habits and travel better.

The characters of The White Lotus engage with their surroundings only insofar as they serve their narratives: a backdrop for personal reinvention, a setting for melodrama, a place of status. Travel, at its best, is not about consumption or show but engagement. The narrative encourages us to step into a place with humility rather than entitlement, recognise history rather than erase it, and understand that the privilege of being a tourist carries responsibility.

The irony is that even as we tell ourselves we would behave better than the show’s characters, we are still drawn by the same impulses - desire, imitation, beauty and the pull of place. But perhaps the greatest act of resistance is to travel with awareness, step out of the mimetic loop and recognise that if The White Lotus inspires us to travel, it should also make us interrogate how we do so - to question who is benefiting from tourism and what positive tourism looks like.

Inspired? Read the rest of The Tourism Leakage Series now!