The Azores is an archipelago of nine volcanic islands in the North Atlantic Ocean, and an autonomous region of Portugal. Inland you’ll find dormant volcanoes, mist-shrouded laurisilva forests and bright turquoise crater lakes, while waves batter black sand beaches. The surrounding ocean is teeming with marine life, including 28 species of cetacean (a third of the world’s species). These include sperm whales and Risso’s dolphin(resident year-round), as well as migratory species such as blue and minke whales.

The archipelago is one of the top spots in the world for whale watching, and a trailblazer for sustainable tourism. So it might surprise you to know that whale hunting was practised there until 1984.

How did the Azores transition from hunting whales to implementing a sustainable whale-watching programme? To find out, we spoke to Rui Rodrigues, owner and director of Futurismo - an Azorean whale watching company - and his marketing director Carlos Picanço. They told us about the cultural shift that took place when this transition occurred, and why whale watching is a vital part of raising environmental awareness on the islands.

Whaling as Cultural Identity and “Açorianidade”

Whale hunting first started on the Azores through the influence of the American colonists, who often stopped at the archipelago for provisions on their way to the New World.

“The Azorean people got curious about the sailing boats and what kind of business they do,” Rui explains. “It was a way for the Azoreans to migrate to the United States, to the colonies. It seems they got good at the job; they started being captains of their own boats and some of them returned to the Azores. They started whaling businesses here in the 19th century.

“At the time, it was hard to live on these islands. The food was not so much, the money was worse. And so whale hunting became a way to get some money, to enable families to to pay for the groceries, school and clothes. That's why it was very important in all the islands.”

Imagine taking whaling away from a culture of people who had no notion of environmental ethics. Whales were a tool for survival but those whalers were also able to change lives

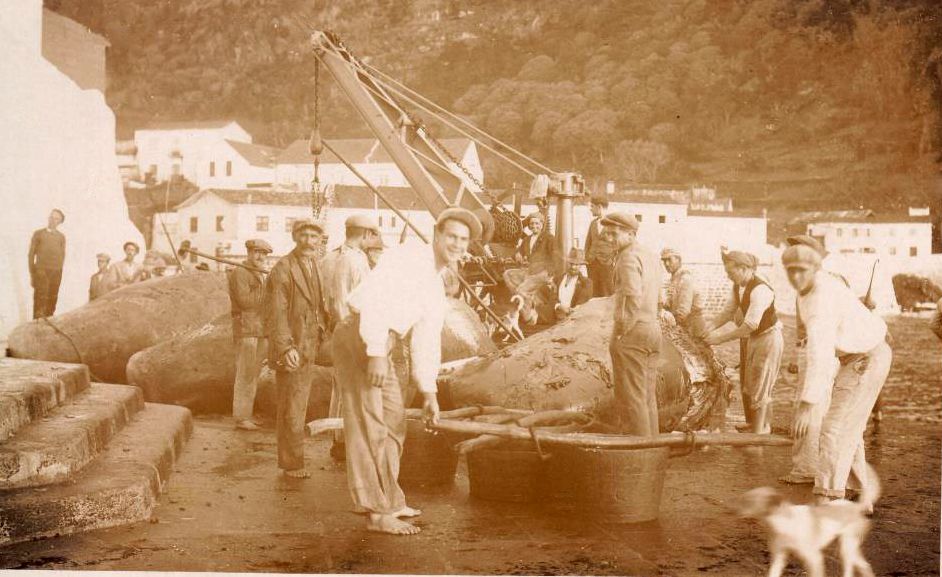

The Azoreans quickly established a culture of land-based whaling. Lookouts would survey the ocean with binoculars from towers onshore, and when whales were spotted the whalers would head out to them on small boats. The whales were caught and brought back to shore. Their blubber was boiled down to make oil, which was sold across the world for use in oil lamps, soaps, margarine and lubricant for machinery. Baleen - hard discs found in the mouths of some whales - had a variety of uses, such as corsets and toys. Whale products were once as common and ubiquitous as petroleum and plastic are today.

“But whaling was about more than money. It’s a cultural thing, part of our identity. You have not only the canoes, but all the artworks made with the whale bones, the scrimshaw,” Rui says.

In other words, whaling became a part of ‘Açorianidade’, or Azorean identity. Even so, it’s easy to look at whaling from the perspective of a 21st century westerner, as an unequivocally ‘bad thing’. Not only is it a cruel practice that depletes whale species numbers, it's also bad for the environment - according to one study, when it comes to carbon capture "one whale is worth thousands of trees". But Carlos, who has a masters in environmental ethics, believes it's important to place whaling within the cultural context of its time.

“Whalers were not tough guys, or bad guys. They were farmers. Most of them could not swim. So, imagine the courage and the despair to go,” he says. “Someone would see a whale with the binoculars and send a flare, then all the men would rush to help, and the women would rush with them. Imagine seeing your husband going to sea and knowing that he cannot swim. Call it a pilgrimage. There was faith involved, the community was gathered. And we must be pragmatic - people were starving.”

“Imagine taking whaling away from a culture of people who had no notion of environmental ethics. Whales were a tool for survival but those whalers were also able to change lives.”

By the 1960s, however, whaling was declining, in large part due to the advances in the petroleum industry. By the time it was outlawed in the 1980s, most Azoreans had ceased whaling altogether, aside from the inhabitants of Pico Island.

“It was more than a business for them - there was such a strong whaling culture,” Rui says. “They believed a man was only a man when he went to hunt whales. We can basically say that whaling died a natural death everywhere except Pico Island, where there was such a tradition of whale hunting. It was a huge discussion in Pico because they still wanted to hunt even though they had a lot of problems selling the oil.”

An Azorean deputy was tasked with negotiating the transition away from whale watching with the EU. He was a biologist who had been impressed with the whale watching culture in America, and wanted to implement it on the islands.

I believe that cetaceans are a big part of this definition of ourselves as an autonomous region - they’re not from the mainland. They’re ours.

“He tried to persuade the people from Pico to make the change from whaling to whale watching, as a kind of compensation. He had money from the EU to help. But the people didn’t react very well to the proposal. They went out in '87 to hunt two sperm whales. It was a defiant gesture, but they did it. But of course the hunt was extinct, because the business already died,” Rui explains.

It was a French sailor, Serge Viallelle, who first started a whale watching business on Pico Island. The municipality supported him financially to get his small rib boats up and running. There was some publicity from foreign press, and tourists began coming to the Azores to do whale watching. Over the years, it has slowly increased in popularity.

But how do Azoreans feel about whale watching? Has it proven a good enough cultural and financial replacement for hunting whales?

“There are those who don't care too much about whale watching; they really care about the heritage of whaling. It’s one of the things you will see here in the Azores. People are more concerned about preserving that tradition. There are museums, they preserve the canoes. There are several festivals where they do canoe races - they take it seriously, more seriously than football,” Rui says.

However, both he and Carlos have seen a huge change in how Azoreans talk about the whales and dolphins, as people become more conscious of their importance. This has increased since a group of academics, companies and individuals successfully applied for the Azores to be certified as a whale heritage site (by the World Cetacean Alliance).

“We do education in schools, our company takes people out. We do citizen science projects; we connect with photographers, and now there’s so much promotion of the whales,” Carlos says. “We’ve started seeing more publicity, like artists drawing paintings on walls of whales and dolphins - you can feel that people really enjoy them.”

“It's a huge change, but I do believe it's always been part of Açorianidade, which is the sense of belonging to an island. Under the Portuguese central state, we are always fighting for our autonomy to be recognised. I believe that cetaceans are a big part of this definition of ourselves as an autonomous region - they’re not from the mainland. They’re ours. More and more they’re helping us define who we are, what we have, what makes us different.”

The Benefits of Whale Watching

Whale watching is now one of the key industries on the island, and has many benefits.

“If people come to the Azores to see the whales, that means money coming to the Azores. That means hotels, restaurants; everything benefits,” Rui says.

“It also helps employ scientists. The university cannot finance the boats going to the sea - they come with the whale watching boats,” Carlos adds. “That’s why our database is bigger than the university. We employ nine marine biologists from the local community right now and this summer we go to 15. We also employ 50 people in the company, full-time all year-round.”

But the benefits are far more than just financial. Futurismo has been collecting cetacean occurrence data during its whale watching trips since 2008, leading to a database of over 15,000 records shared with national and international institutions. Its marine biologists have published 11 cetacean ecology studies in peer reviewed journals. And it’s not just the scientific community benefiting. Rui believes that whale watching trips also help educate those onboard.

“Through whale watching we can show people the biodiversity of the Azores,” he says. When people think about whales, they used to think about sperm whales. Nowadays, everybody knows we have blue whales, fin whales, and several species of dolphins. The people of the community that are interested in that, they talk about it.

“And of course, the most important thing about whale watching is protecting the whales - the more we know about them, the better we can protect them. We know when they are passing, what they eat, what we should do in the presence of whales and dolphins. On a trip, we aren’t just seeing whales and dolphins, we are informing and teaching people about those cetaceans’ lives, the behaviours, the needs, the problems, the risks, everything. I see it as the best opportunity to educate people about these animals.”

“Our motto is ‘explore, love, protect’,” Carlos adds. “‘Explore’ means that by going out you accept the risk of the unknown; you put yourself out of your comfort zone. Then you start loving because of the interpretation that we do. When our passengers go out to sea they're not just waiting for a tail or a fin. We're talking about love. Anger. Universal concepts that you understand are placed on the animals. You can see people's faces when we do that. Protection comes from love. Human beings are selfish - if we can relate with something, we will have the urge to do something.”

How Sustainable is Whale Watching in the Azores?

When whale watching was established in the Azores, regulations were put in place to manage it. These were modelled on whale watching regulations in New Zealand, and include rules for approaching the whales, such as restricting boat speed to two knots and positioning themselves behind the animals so the water ahead of them is clear. There are also laws restricting the number of boat licences that can be granted per island, which helps prevent overtourism.

“Since we started whale watching on São Miguel in 1995, there are only licences for 20 boats,” Rui says. “Since the beginning these are subject to decrease if impact studies say it’s necessary - so if there’s too much impact, we have to accept that the number of boats has to be reduced. But as the number of boats is fixed, we have to increase the size of the boats to respond to demand. We have moved from ribs, which seat 12, to larger boats up to 20 metres.”

“Overtourism is a word too often used,” Carlos adds. “What should be used more is ‘poorly managed tourism’, which is where most problems lie. One of the things we have been doing is fighting for better management of tourism in the Azores, not just in the sea but across the tourism sector as a whole.”

The most important thing about whale watching is protecting the whales - the more we know about them, the better we can protect them

“At the moment, we have been fighting with the association to make sure that the number of boat licences isn’t increased,” Rui says. “20 boat licences still concerns us - it’s not good to have six or seven boats operating in the same area all the time. During summer, we try to distribute them on different parts of the island to avoid being too close to the other companies.

“I think the way we're whale watching - even if people say they are pursuing the whales too much, or there’s too many boats - when you put it on a balance, the benefits of whale watching outweigh any negative effects. And that’s not only for the humans, or about the economy - it’s also important for the animals. Whale watching is the best way to educate people about cetaceans.”

Inspired? Check out our adventures in Portugal.