The West Kernow Way is a 230km, mostly off-road bikepacking route in Cornwall, that winds a figure of eight between Penzance, St Just, Portreath and the Lizard. With over 4000m of ascent and sections that can get very muddy in winter, cycling it will definitely be an adventure. This is the newest cycling route put together by Cycling UK and yet it is also, in part, ancient - taking in lost ways and trails that have been used for thousands of years. Although not necessarily on bicycles.

“The idea of it is to encourage people to explore by bike, rather than driving around,” says Sophie Gordon, Campaigns Officer for Cycling UK. “Have an adventure and discover more of the landscapes and history and culture - joining up all these interesting sites with little trails that riders might not have found otherwise.” The route comes after the success of the 350km King Alfred’s Way, launched in the South East last year. “It was massively popular, in a way that wasn’t expected,” says Sophie. Especially as an off-road trail that could be done in three or four days, without too much time taken off work. The West Kernow Way was their next step.

“We picked West Cornwall because Penzance and Marazion were a big focus,” with local cycling infrastructure getting an upgrade. Then it was time to hit the maps. “The idea is we’re not building anything new,” explains Sophie. “We’re looking at what’s there and thinking how it could be connected in clever ways. It takes quite a lot of work to figure out.” This process can take years.

The specifics of designing the trail were more complicated than you might expect. “In England, on average, about 22% of rights of way are open to cyclists. In Cornwall, it’s lower than that,” explains Sophie. “That’s not a lot at all: they’re mainly footpaths. So it’s really challenging to try to create a cycling route that’s mostly off-road.” But as they searched, their research led them to Lost Ways: routes that have been forgotten over time.

You get that feeling when you’re riding on it across this isolated moor, like you’ve been transported into the past.

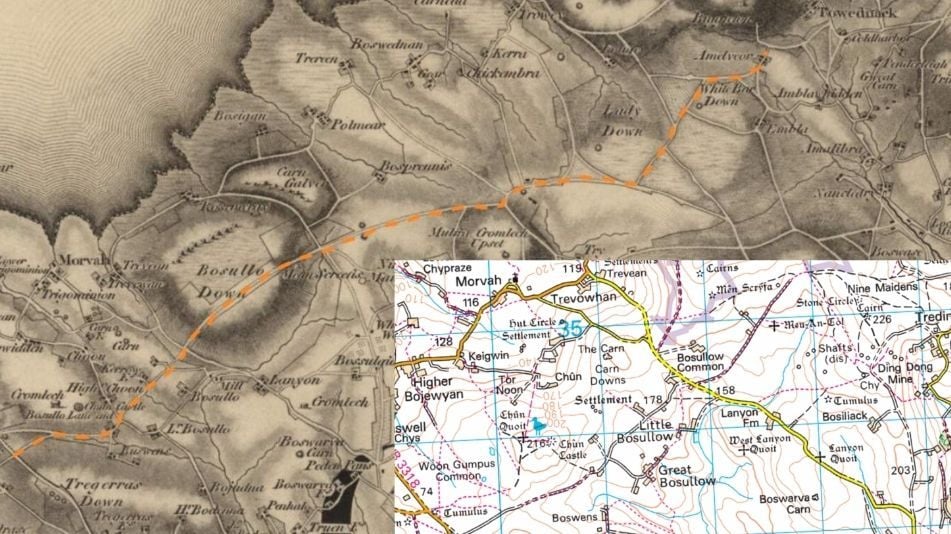

“For example, there is this gravel track across the moors. It’s marked on maps as the old St Ives road, between St Just and St Ives, going back to 1699. It’s clearly been used for a very long time, but it’s become a bit patchy on modern maps. There are bits of it that are footpaths and bits of it that are just a white track, that are not officially a right of way. It’s not a continuous route any more.” More recently, it became known as the Tinners’ Way, with its use for the old tin mining industry around St Just.

“It looks like an old road or a big wide track and you think: why should that just be a footpath? You can see it going off into the distance across the moors and imagine people travelling along this for hundreds of years. There’s amazing research that’s found archaeological evidence of it being used from Bronze Age and Neolithic times. It’s a really cool route. You get that feeling when you’re riding on it across this isolated moor, like you’ve been transported into the past.”

Sophie and her team have put in an application for the status to be upgraded, but it’s a long wait. “It could take 15 to 20 years for that to be processed and go through, because the councils have such a backlog of applications that they’ve got to assess. And it’s just not practical to wait that long, when the evidence is there that these historic access rights exist, so we think it’s reasonable for people to go on using it while we wait for it to be officially processed.” 2026 is the cut off year for all unmapped rights of way to be registered in the UK, after that the ways will be lost forever.

But Cycling UK are confident about including the Tinners’ Way and several smaller Lost Ways on the route. “What we’re saying is that it might be marked as a footpath on a map or on the ground, but in these cases it doesn’t count as a trespass, because you already have a right to use it going back hundreds of years.”

Protecting rights of way is something associated more with hikers than cyclists in the UK. “I think there are lots of people who cycle off-road and haven’t really thought about it before,” says Sophie. “We’re just trying to get people to think about it… We want to show that there are huge benefits to this [continuous cycling routes] and it’s being made more difficult by this inflexible system that we’ve got.”

Once the West Kernow Way was ready to test, several groups of riders put foot to pedal and gave feedback. I asked Sophie what it was like to finally get to ride the route she’d spent so long creating. “That’s the magic moment. Because you spend so long looking at it on a map, on a piece of paper, trying to visualise what it might be like... but you can’t really. And then you go there and think, ‘Ah yes! This is it! This is actually what it’s like.’ It’s always very exciting.”

“But then there are always bits where you ride it and think, ‘actually, this is a lot more muddy or a bit more difficult than I imagined, maybe we should rethink this section.’ So we go back to the map and see where we can tweak it." It’s an ever evolving and improving process. Even in the past few months since launch, it’s been tweaked from riders’ comments and feedback from local cyclists.

“But then it’s hard to actually call them finished. Even King Alfred’s Way is still not the ideal route we’d like it to be. There are a couple of places where it would be lovely to do an alternative route, but it’s a footpath. If that could be upgraded, then you could make the route even nicer by taking it that way instead of on the road. In the case with the West Kernow Way it could be 20 years before it’s officially there.”

You can find out more about the Stories of the Lost Ways, with Cycling UK's interactive map. Or grab a bicycle and head out on a Remote ride across the world.