“I’ll get to checkpoint one and see how I feel,” I thought to myself, as I rode through the rolling hills of northeast France beneath grey skies; the drizzle forcing me to reach for my rain jacket for the umpteenth time. I was barely 12 hours into a two week race when the first thoughts of scratching entered my head. These were never serious thoughts. I had put in way too much effort to just get to the start line to quit, and then there was the amazing support from family, friends and colleagues. Scratching at any point, let alone the first day would be a total no-no.

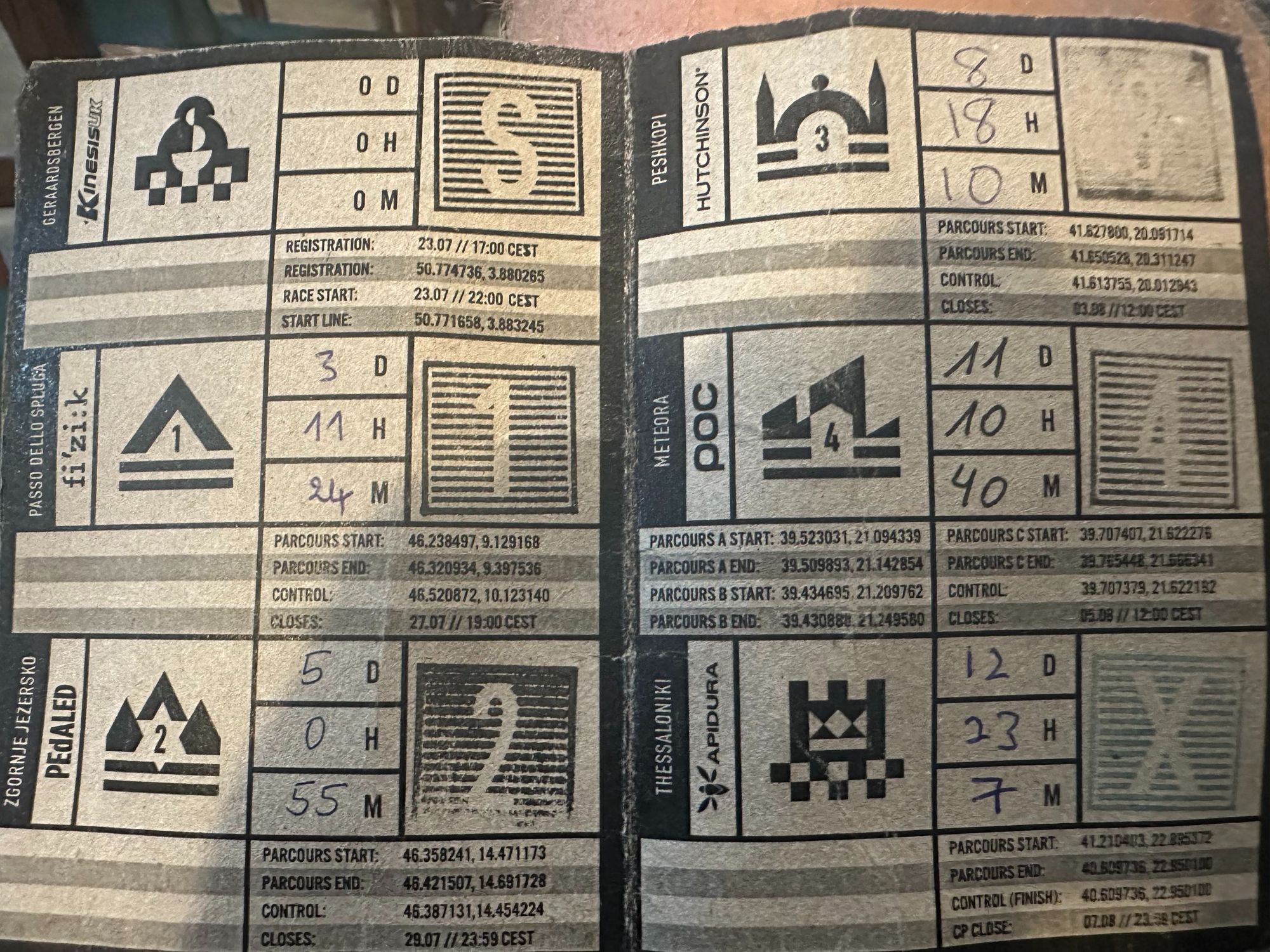

The Transcontinental Race (TCR) is an unsupported bikepacking race that crosses the entire continent of Europe via a series of mandatory checkpoints (CP) and set parcours. Riders are allowed to choose their own route between the CPs, which means weeks of planning and agonising over whether to go over or around any hills or mountains in the way, or whether to pick a faster, busier trunk road over a quieter, usually slower side street or cycle path.

I was so cold I had to stop and warm myself up with the hand dryer in the Saint Moritz train station toilet.

Riders must carry everything they need for the journey with them, and no outside assistance is allowed. I was one of 350 entries into this year’s race, which started in Geraardsbergen, Belgium and finished in Thessaloniki, Greece - via control points in the Italian and Slovenian Alps, Albania and Greece. Depending on the chosen route, riders would need to cover around 2,175 miles (3,500km) and climb 40,000m over the course of the 9-15 days it might take.

My journey would take 13 days, from the lows of the French drizzle to the highs of Greek mountain passes. It would be a journey of extreme colds and scorching hots, of perfect asphalt, potholes and rough gravel, from the Livigno singletrack to boulder-strewn Albania and beyond.

My background is in mountain biking. I have lived in the French Alps for nearly 18 years as a result of that passion. I had foreseen that the flatter bits of the TCR would likely be my nemesis, and so it proved on day one. The rain and headwind didn’t help matters, but I knew that when I got into the more familiar territory of the Alps, things would get better - and they did.

By the end of day two, despite the utterly miserable weather, I had made it over the Vosges and the Jura and into the Alps themselves. The sun finally shone on day three as I rode over the Gotthard pass and down into the overtly Italian (aside from the prices) part of Switzerland.

After another couple of 2,000m passes and a super fun, technical descent from the Passo della Spluga with it’s 50+ switchbacks and numerous narrow tunnels, we were in Italy proper and the thermometer was showing 30°C (some 28°C warmer than the top of the Gotthard that morning). I had covered nearly 1,000km in the first three days with barely seven hours of sleep, so it was time to stop for a ‘proper’ rest - by which I mean five hours. Rest is a relative concept on the TCR.

After a 4am alarm, day four saw me climbing back into the Swiss freezer, over the high Maloja pass and down to Saint Moritz. I was so cold I had to stop and warm myself up with the hand dryer in the Saint Moritz train station toilet (a very common occurrence amongst my fellow competitors I would later learn). More mountain passes followed when I got back on the bike. I rolled into CP1 in Livigno, a ski resort in Lombardy, in the Italian Alps, at 10am, cold, hungry and 93rd in the race.

The first real routing decision followed: either go over the Stelvio pass, or take the off-road option through Val Mora, which would cut out over 2,000m of climbing, but would be slower going due to the rocky terrain. As a mountain biker at heart, this was an easy choice and one I was looking forward to - the off-road was just the motivation I needed to keep going. Scratching? No chance.

After the gravel came the immaculate Italian cycle paths down to and out of Bolzano. Although I had some tyre issues (both tyres blew off the rims in quick succession covering me and my bike in tubeless sealant after I had accidentally over-inflated them - whoops), I was happy with how things were going. I rewarded myself with a radler, in a radstation, on the radweg. That pleased me no end. I rode on beyond midnight, looking for a suitable spot to bivy out next to the road.

The first real routing decision followed: either go over the Stelvio pass, or take the off-road option through Val Mora, which would cut out over 2,000m of climbing, but would be slower going due to the rocky terrain.

Still in the mountains, I woke up with the cold at around 4am and carried on. Since I’d gone to bed in all my riding kit I was rolling within 20 minutes of waking. I reached CP2 by 11pm that night, day 5, after crossing into Austria, back into Italy, and then finally into Slovenia.

At the checkpoints there’s a busy meeting of riders, some just leaving, some staying. I found a spot to rest my legs under a table in the entrance way, but the following morning came far too quickly and I was rolling again by 5am. The second parcours brought the first section of mandatory gravel. The organisers were gentle with us: this gravel was a smooth way to exit the Alps and descend down to the flatlands (and heat) towards the Croatian border.

The source of much joy and comfort, left, and the source of much pain and suffering, right. Photos: Guy Bowden

Zagreb was a culture shock after nearly a week out in the relative wilds. The eight-lane city streets, traffic lights and bustle of a major city in the heat of the afternoon wasn’t a lot of fun. I just had to get through it and on towards the Bosnia & Herzegovina border crossing the following morning. It wasn’t until my 10th border crossing and 8 days into the race that I finally had to show someone my passport. After skipping the three or four kilometre queue of traffic, I finally left the EU and entered less familiar territory. The first thing you notice are the minarets of the numerous mosques (51% of the population are Muslim). The next thing you notice, sadly, is the rubbish and the knackered roads. Lastly, the price of everything halves: from food and drink to hotels.

The morning brought some heavy rain which cooled the temperature, and the afternoon was perfect riding conditions, with broken clouds and 25°C. It was only a week after a heatwave had been serving up 40°C around the Balkans, so we counted ourselves lucky.

My route choice matched the majority of the pack, taking the direct but hilly way through central Bosnia, just south of Sarajevo and on towards the north west corner of Montenegro at the confluence of the Tara and Piva rivers. The other option was to stay in Croatia and follow the Adriatic coast southeast, or take a more northerly path through Serbia, avoiding the mountains. I chose the Bosnian option as I had previously cycled in the area and was less worried about the unknowns that others may fear: dogs and traffic, to name but a couple. The stretch between Banja Luka and Niksic (Montenegro) was some of the most beautiful of the entire trip.

After feasting on a hearty vegetable risotto in Niksic come dinner, I descended to sea level just after the sun set. Even at 9pm, It was like riding into an oven from the relative cool at 600m.

The 100km or so of flat through the Montenegrin capital of Podgorica the next day, and on to the Albanian border, was fiery hot. Never did I think I would be thinking longingly for the rain of northern France to return. The mid-afternoon climb up to the CP3 in Burrel was brutal. I lost count of the number of stops I had to make to buy water, coke and ice-cream along the way. I was stopping at nearly every roadside water spring I passed.

The sun hangs high in the sky at these latitudes throughout the middle part of the day, offering very little shade from the roadside shrubs and trees. It’s not until around 6pm that it rapidly descends toward the horizon, leaving you with around three hours of daylight in more pleasant temperatures with which to ride.

The third mandatory parcours was a full on dirt track affair: the SH36 “road” to Peshkopi, in northeastern Albania. This was the first real test of bike setup and off-road handling. It would punish those who brought pure road bikes with them, and reward those who opted for a more gravel oriented set-up. Having brought my gravel bike with some 42mm tires all the way from Belgium with me, I was looking forward to the challenge and enjoyed the entire 40km, passing quite a few riders who had to nurse their bikes across the rough terrain.

None of the other riders you meet expect help fixing things - nor do the self-sufficiency rules allow it - but there is a camaraderie in the small talk with others you meet on the road; where did you sleep last night? Where are you aiming for today? Questions only sensical to a TCR rider.

Zagreb was a culture shock after nearly a week out in the relative wilds. The eight-lane city streets, traffic lights and bustle of a major city in the heat of the afternoon...

There’s also a freedom to ride on at your own pace, even if that means dropping that rider behind. Odds are you’ll see them again later that day, or the next morning, for a similar catch up.

I made it to Peshkop around midnight and gave myself a lie in - setting my alarm for 6am - and finally taking advantage of the breakfast included at the hotel for the first time on the trip.

It was a slow morning on day 9 in Peshkopi. I hadn’t got to this point totally free of punctures. Since my blown tyres in Italy I had resorted to running an inner tube in my rear wheel, and picked up quite a few punctures along the way. I was now out of spare tubes and had one patch left. I dedicated a few hours of my lazy morning to fixing what I had, and finding a few more patches before continuing. I was invited for a coffee by some locals and had a nice conversation about the race and how great they thought it was that we were travelling through their beautiful country, dispelling myths that fear-mongering press and right-wing politicians would have you believe.

The break from “racing” was most welcome. It was way past 9am by the time I finally got riding again: on into North Macedonia, before heading back into the far south of Albania near the Greek border. I stopped riding by 10pm, which meant barely 10 hours of actual riding time that day. I needed the relatively easy day to recharge my tired body and mind.

I reached the final border post of the journey before 7am. The customs officers weren’t in much of a hurry, but I rode into Greece feeling strong and ready to tackle what would prove to be the toughest day of the race. The fourth parcours was split into three parts. Each section was asphalt, but between them the riders had to make a choice between a much shorter, but tougher off-road mountain pass, or a longer, tarmac way around.

For me there was no decision to be made, the off-road suited me and my bike setup way more than the way around. It seemed also that the shorter option was just too good on paper for the majority of riders to pass up. I met a fellow gravel bike rider on the way, and we passed various riders on road bikes heading both up and down the rugged mountain pass. We were definitely in mountain bike territory here.

That evening I sat down for a chicken kebab with Patrick, a rider sitting in the small town square of Mesochora when I got there. His tale of misfortune would go down as one of the stories of this years’ race.

Patrick was riding on a fast road bike setup with skinny tires and road shoes. He hadn’t enjoyed the SH36 in Albania, so he knew that the mountain shortcut was not for him. Instead, he went the longer way around to avoid punctures and mechanicals. Unfortunately they found him anyway.

I had the surreal experience of riding out of town whilst the last of the party goers were being kicked out of the bars and making their ways home via the numerous kebab shops.

On a steep incline, he punctured in his rear wheel, and after fixing the flat, he accidentally dropped the wheel, which then took off down the road, eventually settling in the undergrowth. When Patrick retrieved the wheel, the cassette was missing. 45 minutes of searching, swearing, and sweating in the midday heat later, he slipped and fell, and when he stopped swearing, he found himself staring directly at the missing cassette - but when the wheel and cassette were secured safely back in the frame, he realised that the freehub was not engaging. He had no drive. The ratchet system that means you can freewheel one way and drive the wheel the other way was gone.

More swearing and some tears followed as the reality of being half way up a Greek mountain, with no means of fixing his bike dawned on him. His only real option was to walk the uphills, and coast the descents. He had spent the seven hours prior to our meeting doing just this.

The rules of the TCR state that any forward progress must be made under your own power. When I sat with him, Patrick was waiting for a taxi to travel the 80km (and 1,000m downhill) to the nearest bike shop. He would get his bike fixed the following morning and then have to ride the 80km back to this point before continuing his race. Miraculously, he made it to the finish within the cutoff time - albeit 24 hours later than he might’ve done otherwise. Chapeau Patrick.

The following morning, on day 11, I got to the final checkpoint in Meteora. After the gruelling day in the mountains, I opted for the longer, flatter route to the finish. I hoped to get to Thessaloniki within two days of riding. The flat route looked good on paper, but that was before any headwind, heat or traffic was taken into account. I must have stopped at every gas station along the way to fill up on lemonade, coke and water. Having started at 4:30am, I reached my hotel by 10pm that night. I had 290 km left for my final day of riding.

Another 4am alarm, and I was rolling by 5am. Having stopped in the city of Katarina on a Friday night, I had the surreal experience of riding out of town whilst the last of the party goers were being kicked out of the bars and making their ways home via the numerous kebab shops.

It was going to be another roasting day under the Greek sun. The temperature in the shade was around 39°C, and my Garmin was showing 44°C in the sun. The cruel organisers had set the final 147 km parcours to the north of Thessaloniki. Meaning we would pass within 10km of the finish on our way to the start of it. It featured a good section of sandy gravel which was great (for me at least) then a very hot southerly route towards the city. After negotiating nearly 2,175 miles (3,500km) across Europe, and entering the city limits of Thessaloniki, the final sting in the tail awaited: a 5 km tour of the city's steepest, roughest streets, some topping out at over 25%.

I was definitely cursing the course designer at this point.

This was not a nice, congratulatory way to finish a two-week bike race. This was a kick in the teeth. The blessing (by design I imagine) was the final kilometre of flat seafront bike path to quell the murderous thoughts going through my head. And the relief at crossing the finish line (along with the cold beers) was more than enough to forget the torture. 12 days, 23 hours and seven minutes after setting out from a damp town in Belgium, I was the 65th rider to cross the line - and one of just 153 of the 350 starters to finish. It was all over, done, finito, finished.

Inspired? Check out our full range of cycling adventures now!