The first man to climb a Munro in Scotland is said to have been Mad Colin Campbell of Meggernie, who scaled Stuchd an Lochain several hundred years before the concept of 'a Munro' was devised. The local laird of Glen Lyon is said to have climbed the 960m (3,150ft) mountain in 1590. The Sunday Post writes that “he wasn't interested in bagging peaks” but “rather he wanted to chase a herd of wild goats off the summit cliffs to their deaths in Lochan nan Cat below". No surprises why Mad Colin got his nickname, then.

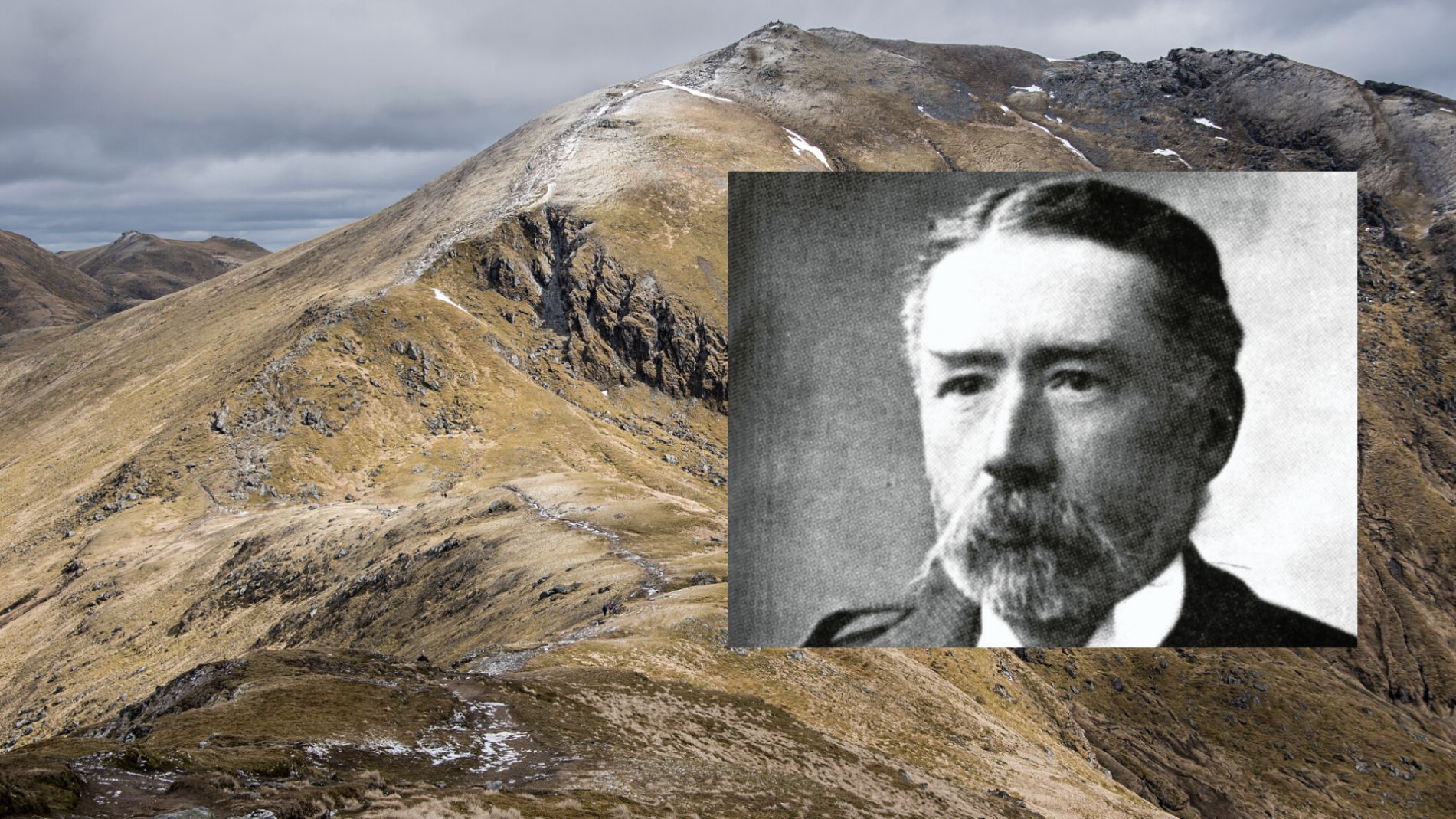

It wasn’t for another three centuries that Sir Hugh Munro would publish his “Tables giving all the Scottish mountains exceeding 3,000 feet in height", in volume one of the sixth edition of the Scottish Mountaineering Club (SMC) Journal, in September 1891. The tables listed 538 tops over 3,000ft, of which 283 were considered distinctive mountains. His tables would change hiking in Scotland forever - birthing the 'Munro', and the challenge of “bagging” them.

“Compared with the Alps, our Scottish hills are but small, but they have all the characteristics of mountains, and when seen in winter and early spring it is difficult to realise that the ordnance surveyors have not been mistaken by some few thousands of feet.”

You’ll notice that Sir Hugh’s 283 is one more than the 282 notes in our headline. Munro’s list, and the manner in which ‘tops’ were separated from distinctive summits, caused debate then as it does now. Some Munros on the original list are no longer considered as such, while others, like the Inaccessible Pinnacle in Skye, have gained Munro status. "There have been only four major revisions; in 1921, 1953, 1981, and 1997," write the Scottish Mountaineering Club, in their biography of Munro. "With the increasing accuracy of heighting technology, some hills have been promoted, others demoted."

The latest change came as recently as September 2012, when Beinn a' Chlaidheimh was downgraded to a Corbett (which is a mountain over 2,500ft but under 3,000ft). But what of the man behind the tables?

Sir Hugh Munro was born into a wealthy family in London, on 16 October 1856. Munro would be raised between the English capital and the Munro’s 3,000-acre estate in Lindertis, near Kirriemuir, in Angus, Scotland. Lindertis is on the edge of the Eastern Grampians, and would provide the base for many of Munro’s mountainous excursions. The wider Grampians take up nearly half the land mass of Scotland, and are home to iconic peaks, from Ben Nevis to Ben Macdui.

In his excellent book Munros: A History, Andrew Dempster describes how as a youngster, Hugh Munro's great delight was in collecting, “categorising and classifying” things “with extraordinary attention to detail”, such as fossils and butterflies. Dempster writes that it “goes far in explaining his consequent suitability for collecting and classifying Scotland’s 3,000-foot summits.”

Munro’s love for hillwalking is attributed to his time spent in the Alps, during a visit to Stuttgart to learn German at 17. It was a love he brought home to his base at Lindertis. While Ben Lomond is the first Munro that many now climb, the first recorded 3,000ft peak that Munro ascended was Ben Lawers, in 1879.

Munro spent time in South Africa from 1880 after an attack of pleurisy, then returned to Lindertis. In 1889 he would become a founding member of the SMC in Glasgow. “That Scotland is a wild and mountainous country, is the excuse for the formation of a Scottish mountaineering club," he wrote.

There is little doubt that the lists will receive the study they deserve at the hands of all who are interested in the mountains of Scotland.

Munro went on to serve as the SMC president from 1894-1897, but it would be for his tables that he would be remembered. Joseph Stott, the editor of the SMC Journal, commissioned Hugh to produce the definitive list of 3,000ft mountains in 1889. Munro was 33, and had only been up 42 tops at this point. He set off to climb and measure many more Munros in the following months, and greatly utilised the work of the Ordnance Survey and the knowledge of other climbers.

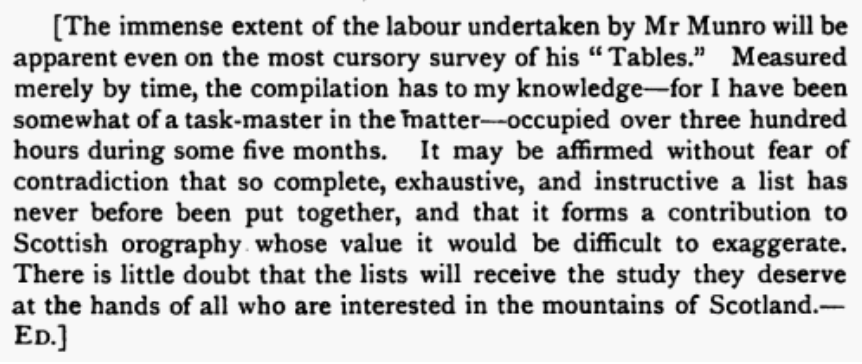

Sir Hugh later wrote that “when first this work was commenced, I had little idea of the enormous amount of labour and research which it would entail,” and his effort is further captured in the footnote of Stott which follows the tables:

Stott was correct on many points, but on the assertion that “the lists will receive the study they deserve at the hands of all who are interested in the mountains of Scotland” - well, he couldn’t have known just how right he would be.

Munro wrote about many of the ascents that he made in journals which are still available to read online. One such article was headlined “Winter Ascents”, and was published in the same volume of the SMC Journal as Munro’s tables.

“We must admit that for purposes of mountaineering, "winter" often extends over a far longer period than the traditional three months assigned to that season by the calendar,” he writes, going on to highlight the beauty of hiking in winter.

“The interest of the walk itself is much increased. The snow is often so hard as to present all the features of the upper part of a Swiss glacier, rendering the ice-axe almost indispensable, and even the rope sometimes necessary.

“If the weather happens to be fine - and there is at least as good a chance of fine weather in winter as in summer - the atmosphere is generally far clearer, and the views therefore more extensive and more distinct.”

Munro goes on to detail a long, snowy walk to the summit of the Cairnwell pass, eventually reaching the top of Glas Moal (1,086m/3,502ft).

“The day was so still that, without feeling the least cold, we sat on the snow and ate our luncheon on the summit of the mountain,” he writes, “enjoying the splendid view and the bright sun. And the air was so clear, that we could plainly see a range of hills to the south-west beyond Stirling, which must have been the Campsie Fells, seventy miles off.

“About the tops we saw a great number of deer, ptarmigan, and white hares, besides an eagle.”

It was ultimately the goal of Sir Hugh Munro to climb all of the tops and Munro summits on his original list, and he got very close indeed. At the time of his death, at 63 years old in 1919, he was three short. He didn't manage the Inaccessible Pinnacle, due to poor weather rather than a lack of trying. He didn't climb Càrn an Fhìdhleir, despite an attempt at night in 1908, and he did not climb Càrn Cloich-Mhuilinn - which he was saving for last.

In amongst all this, Munro was a politician - though never became an MP. He was also a King’s Messenger, occasionally carrying important documents to diplomats around the world. He was a keen traveller, and travelled abroad extensively with his wife Selina and his family. During WW1 he worked in Malta, then later he worked with the French Red Cross in Tarascon, a commune, where he would pass away from pneumonia a year after the end of the Great War.

'Munro bagging' has since become a national obsession in Scotland. The Scottish Mountaineering Club keeps a list of "compleators" - Munroists who have scaled every mountain above 3,000ft in Scotland. The first was Rev. A.E. Robertson, as early as 1901. As of 2021, there are over 7,000 people on the SMC’s list - with the number 284 kept blank for all those compleators who decide not to register.

Scotland’s mountains may not be the highest in the world, but their charm remains unmatched. As Munro himself wrote: “Compared with the Alps, our Scottish hills are but small, but they have all the characteristics of mountains, and when seen in winter and early spring it is difficult to realise that the ordnance surveyors have not been mistaken by some few thousands of feet.”

Inspired? Check out our range of hiking and climbing trips in Scotland, from Hike, Kayak and Wild Camp the Isle of Skye to learning winter skills up Ben Nevis!

This article contains affiliate links. Which basically means we make a little commission if you click through and buy something. It doesn’t cost you anything, and it just means we can do more good things in good places.