Wear a broad hat rather than carrying a parasol. That way you’ll be able to use both your hands to climb. Choose sturdy boots over fashionable footwear on the mountain. Be aware that, as Mrs. Henry Warwick Cole wrote after climbing on the Monte Rosa in the 1850s, “a lady’s dress is inconvenient for mountaineering even under the most careful management” - and don't be surprised if your character is called into question on your return.

The earliest record of a woman hiking for leisure in Scotland dates back to c. 1770, when the London-based travel writer Mary Ann Hanway wrote that despite being unable to find anyone willing to accompany her to the top of Ben Lomond, she had heard locally of “a young Scotch lady that walked up [the mountain] in the morning, and returned to dinner without appearing tired.”

I owe a supreme debt of gratitude to the mountain for knocking from me the shackles of conventionality.

Hanway, a keen walker, contrasts the woman to the “fine ladies” of her own land, “who affect to be tired to death with a couple of turns in the Mall” - and to whom the idea of hiking was “horrid” and “indelicate”. Hanway herself was writing anonymously. Her book A Journey to the Highlands of Scotland was published with the byline ‘By a Lady’, in order to avoid those sort of stigmas herself.

“Most women weren’t comfortable admitting they were doing these things in the 1890s, early 1900s or before,” says Paula Williams of the National Library of Scotland. “They would be questioned by society, and it could affect their families or the people around them.” Williams is the curator of the newly-opened ‘Petticoats and Pinnacles’ exhibition at the national library in Edinburgh, which charts the history of Scotland’s women mountaineers both at home and abroad.

“I was doing some academic reading on mountaineering in Scotland and noticed there were no women,” Paula says. “They just don’t appear in those kinds of histories at all, but women were there. They were in the hills too."

The exhibit documents how, for hundreds of years, women have had to overcome societal barriers simply to justify spending time outdoors. Women who hiked alone were “viewed with suspicion” which turned to “social outcry at imagined impropriety” if they were to hike alone with a male guide. Criticism of their actions didn’t solely come from male voices, either.

“I found the level of snobbery surprising,” says Paula. “Women would ask how they [the women mountaineers] could do that? Look what you have to wear? I would never get hot and sweaty - it’s not ladylike.” Women who hiked were deemed to be “unmotherly”, and Paula notes that “I think there’s still a thing about mothers climbing, and mothers in the mountains.”

The exhibit highlights a quote from Maria Coffey, from 2003, which reads: “when George Mallory disappeared on Everest, he, too, left a wife and small children behind, yet this did nothing to dint his heroic image.”

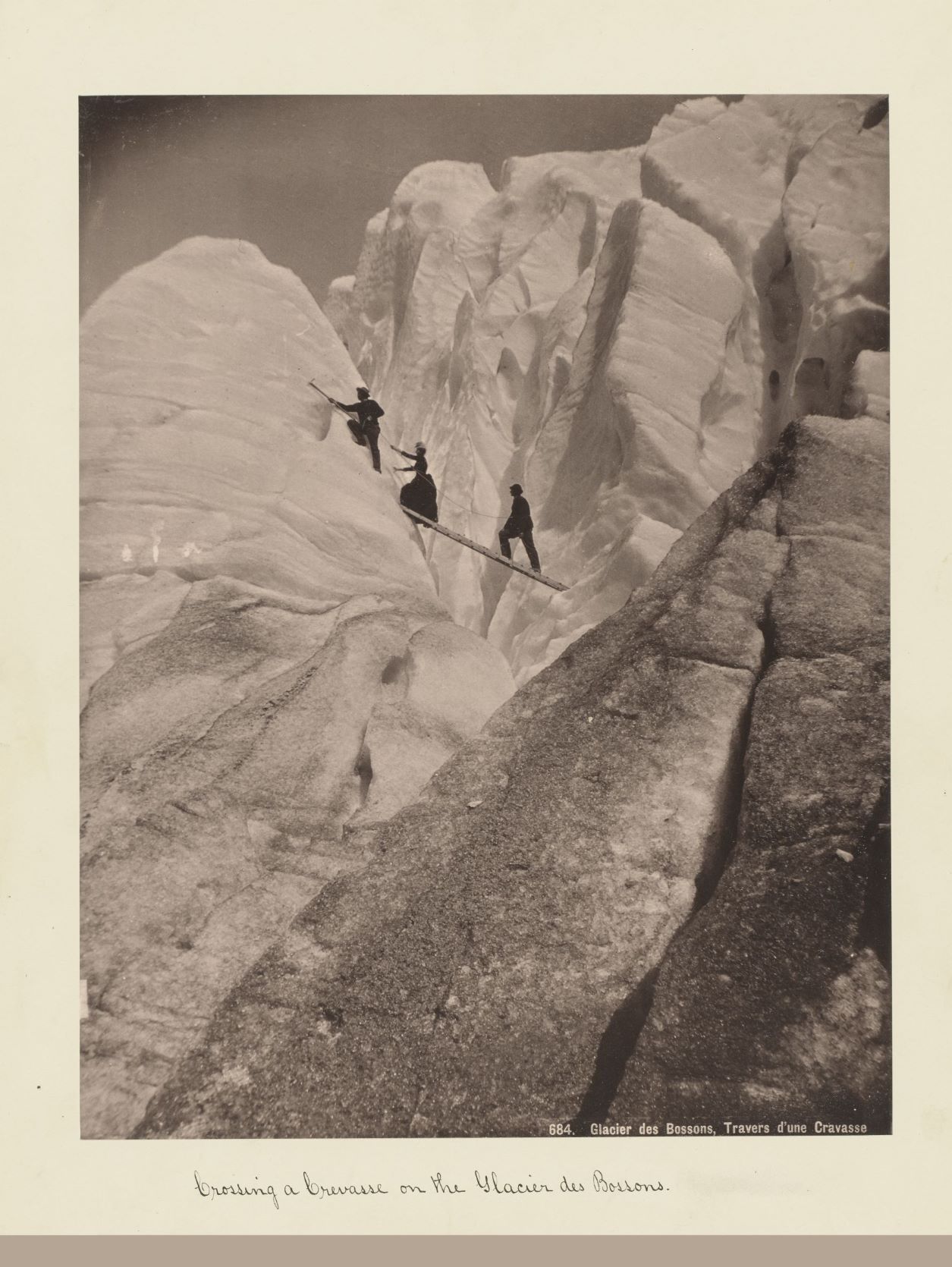

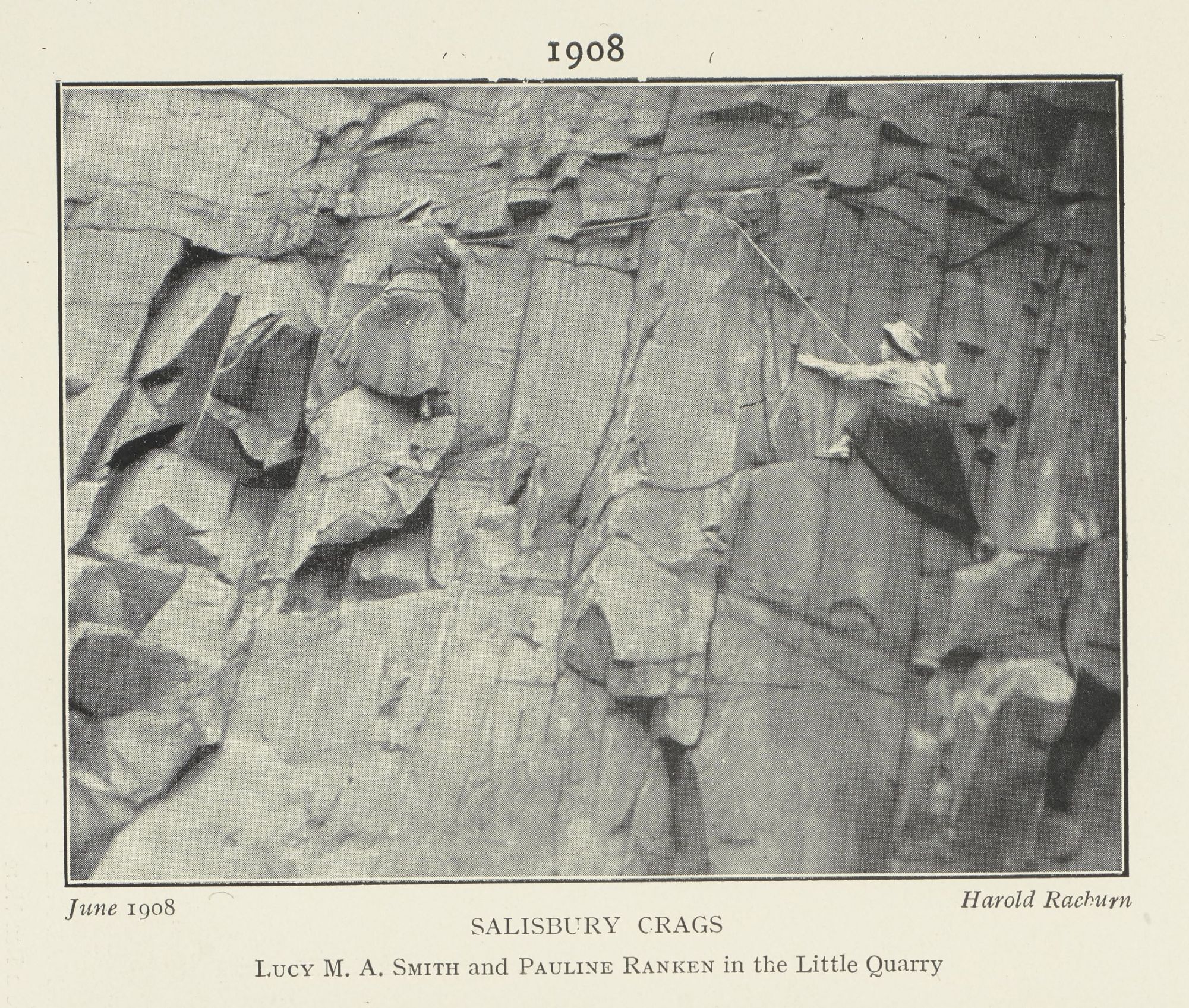

Most eye-catching of all, however, are the images of women climbing in long skirts and broad hats. Claude Benson wrote in 1914 that “some ladies cling insanely to the artificial trammels of society, in the shape of a skirt when climbing.” This only made the climb itself more dangerous, Benson writes, and besides, the skirt would “quite probably get irremediably torn off.”

Women who climbed more frequently would veer towards more practical gear. “They tended to wear long, drawn in pantaloons that came in at the ankles,” says Paula, “Then they would have a knee length or just below knee-length skirt on top of that, which although fairly voluminous would give you room to move.”

For many women of the time, hiking was - as it remains now - an empowering experience. Irish climber Lizzie le Blond, the “foremost female mountaineer of her age”, wrote: “I owe a supreme debt of gratitude to the mountain for knocking from me the shackles of conventionality.” Paula laughs that she thinks le Blond “enjoyed the slight scandal that went with being a women mountaineer.”

...many a time after returning to civilisation I longed to be in the desert again, where the crows and the goats did not care what I wore.

Perhaps pettiest of all was the fact that it became an affront to masculinity for a man to even climb a route completed by a woman. Etienne Bruhl, writing in 1929, lamented that men could no longer climb The Grepon in Chamonix: “Of course there are still some rocks standing there, but as a climb it no longer exists. Now that it has been done by two women alone, no self-respecting man can undertake it. A pity, too, because it used to be a very good climb.”

Williams notes: “There was that whole Victorian thing about male climbing and pitting your body against mother nature. It was slightly sexualised as well, so I could see how women impinging on that would be difficult for men.”

Some of the women featured in the exhibit are well known. Nan Shepherd, author of The Living Mountain, adorns the £5 note in Scotland. Others less so. Anne Grant (1755-1838) supported her eight children through travel writing after the death of her husband - balancing a “ladylike disinterest in commerce” and need for money by publishing anonymously about the Monadhliath mountains.

Jane Duncan was born in Glasgow in 1848, and championed access to higher education for women before defying social conventions to travel the world. She would become the first Western woman to reach the Chang La Pass (5,360m).

Duncan’s humour shines through in her writing. In her 1906 book A Summer Ride Through Western Tibet, she describes the moment when, whilst she was simultaneously eating a scone with one hand and holding an umbrella in the other, the pony she was riding almost fell off of a cliff:

“We got into a very difficult place; but as going hungry into the next world or remaining with sunstroke in this world would not have improved matters I finished the scone and clung to the sunshade, thinking that if the beast did go over with me it would be merely a moment of panic, a sudden shock, and that would be all.”

For Duncan, “one of the joys of the expedition was getting away from dress with its worries as distinguished from mere clothes, and many a time after returning to civilisation I longed to be in the desert again, where the crows and the goats did not care what I wore.”

We later learn about the formation of the Ladies’ Scottish Climbing Club (LSCC) in 1908, in the era when the suffragettes were still campaigning for the vote. These clubs allowed women to lead climb - something gender prejudices about women's strength and skill had prevented them doing while climbing with men.

Jane Inglis Clark made early ascents of Buachaille Etive Mor and Ben Nevis, skiing on the latter. Una Cameron became the first woman to climb Mount Kenya in 1938, and went on to ascend Mont Blanc five times in her life. The Scottish Ladies' Himalayan Expedition took place in 1955 and was immortalised in the book Tents in the Clouds: The First Women’s Himalayan Expedition in 1956.

Why did they all do it? Given all the stigmas and societal barriers in their way?

We’ll leave the final word to Jane Inglis Clark, who wrote in 1938 of how: “the troubles of life seem to fade away in the presence of the everlasting hills. We may go out tired and worn in mind and body; we return renewed and restored: health re-established and friendships strengthened.”

Inspired? Check out our full range of wild hikes, or learn more about the Petticoats and Pinnacles exhibit, which is running at the National Library of Scotland from 10 July 2021 to 28 May 2022 in Edinburgh.

This article contains affiliate links. Which basically means we make a little commission if you click through and buy something. It doesn’t cost you anything, and it just means we can do more good things in good places.