The ancient Mayan city of Palenque, Mexico, sits on a hillside plateau in the south of the country, surrounded by thick rainforest and overlooking the Tabasco coastal plain. In the mornings, the plains are often swathed in mist, giving the impression that the city hangs in the clouds. You can hear the soft burbling of a stream that runs between the buildings, while the surrounding jungle echoes with the calls of howler monkeys and toucans. When it gets dark, the foliage comes alive with the gleam of fireflies.

Palenque is astonishingly well preserved. The excavated part includes the palace complex, a labyrinth of arched hallways and rooms painted with stucco frescoes. Then there’s the Temple of Inscriptions, which records approximately 180 years of the city’s history with hieroglyphics carved into the limestone walls. At the south east of the site lies the Temple of the Cross, so named because of the cross inscription found on its walls - it symbolises the world tree in Mayan mythology.

Visitors to Palenque ruins can climb the stone steps and wander through the rooms and courtyards of the buildings. They can follow walking trails into the surrounding jungle, passing huge trees threaded with liana vines to reach gushing waterfalls. The archaeologists who mapped Palenque estimate that there are around 1500 buildings located within a 16 square kilometre radius. Only 50 have been excavated, and the rest are still lost within the dense jungle. This means that most of Palenque’s history is still hidden.

And what a history it is. Palenque is where myth and history intertwine. A story of kings who created cities so advanced they were accused of being extra-terrestrials; where an intricate calendar inspired modern beliefs of Armageddon. Then there's also the question at the centre of it all - why did the city fall?

The Rise and Fall of Palenque

There’s evidence to show that Palenque was inhabited from around 500 BC. Inscriptions found at the site say that the earliest king was a man known as ‘Snake Spine’, who ascended the throne in 967 BC. As this is long before the city was even built, this is likely a myth. It was between the fourth and ninth centuries - the zenith of the Maya Classical period - that the city flourished, and a dynasty of kings was established.

The best-known king was K’inich Janaab Pakal, who came to the throne in A.D. 615 at the tender age of 12, and ruled until his death in A.D. 683. It was during his reign that many of Palenque’s most ornate edifices - such as the palace complex and many of the temples - were built. The palace is a remarkable feat of early engineering, containing sauna rooms, an aqueduct and even a granite toilet with its own early sewage system. There’s an altar at the base of the palace which was used for offerings to the gods. Human sacrifices did happen (normally high status prisoners of war) but ritual blood-letting ceremonies were more common.

The palace and temples were originally covered in a thick layer of stucco and then painted red, a colour which symbolises life to the Mayans. Scribes carved the history of their civilisation onto the walls in ornate hieroglyphics that were not deciphered for over a thousand years. They did not, however, chronicle the city’s decline.

Contemporary historians and archaeologists believe that a series of interconnecting factors led to the eventual abandonment of Palenque (and other Mayan cities). At its height, Palenque likely had a population of around 6,200 people, many of whom lived in the central area of around 0.8 square miles. Overpopulation would have led to a depletion of natural resources - there’s evidence of major forest loss in Palenque in the Late Classic Maya period - and environmental degradation. An increase in aridification and drought would have not helped matters.

When resources are scarce, living standards begin to decline and dissatisfaction begins to increase. The elite ruling class had control of vital resources, alongside important knowledge and military power. But as people at the top, they were expected to provide security and resources to their citizens, which became increasingly difficult.

“By the end of the eighth century, the ruling elite were unable to deliver on their social promises, despite their many efforts to do so. Intercity conflict increased, perhaps even class conflict, creating a synergy that reinforced the myriad problems in their high-cost human–environment system under aridification,” write Jeremy Sabloff and B Turner, in their 2012 paper on Maya collapse.

“The old political and economic structure dominated by semi-divine rulers decayed. Peasants, artisan–craftsmen, and others apparently abandoned their homes and cities to find better economic opportunities elsewhere in the Maya area, leading to a significant depopulation, even abandonment, of many major city-states.”

And so Palenque was left abandoned. The intensively farmed land around it began to rewild, and thick rainforest regrew around its palaces and temples.

Over the centuries, the Mayans began to leave Palenque, seeking more suitable accommodation - normally in coastal areas, which had become more lucrative due to increased maritime trade. It’s estimated that there are around six million Maya still living in Central America today, many of whom face poverty and discrimination.

And so Palenque was left abandoned. The intensively farmed land around it began to rewild, and thick rainforest regrew around its palaces and temples. For centuries the city remained in the jungle, until the conquistadors arrived and new settlements were established in the jungles and on the coasts of Mexico.

On Aliens, Apocalypses and Kings

In the second half of the 18th century, rumours of an ancient city hidden in the jungles near the tiny village of Santo Domingo del Palenque reached the ears of the Captain General of Guatemala, who began ordering a series of explorations to find it. In 1787, artillery captain Antonio del Rio took a group of soldiers and architect Ricardo Almendáriz into the forest for the first excavation of the city. They cleared the trees with their hatchets, and Almendáriz spent weeks creating drawings of the hieroglyphics which are still used today.

This paved the way for the rediscovery of Palenque, which is still in process. One of the most exciting rediscoveries happened in 1952. Mexican archaeologist Alberto Ruz Lhuillier was excavating the Temple of Inscriptions when he found a stone in the floor with holes on either side, meaning it could be pulled up. Upon doing so, he found a staircase full of rubble and debris.

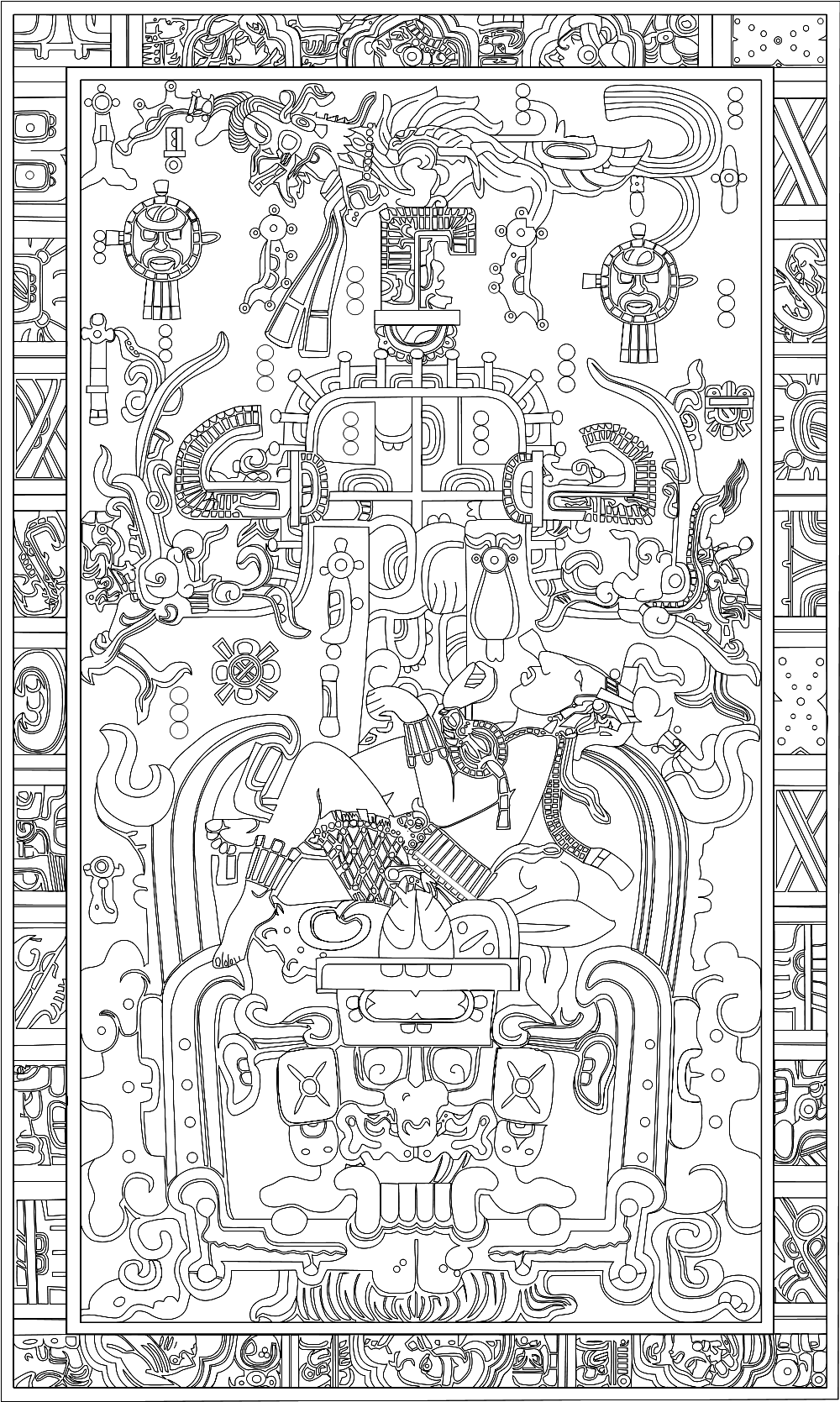

Four years of excavation later his team arrived at the end of a narrow passageway, and found a stone box containing the remains of six human sacrifices. Next to it was a triangular slab, which when pushed aside revealed a funerary chamber and a vast stone sarcophagus with an intricately carved lid. The body inside - wearing a jade death mask and intricate jade ornaments - was identified as Pakal, Palenque’s most illustrious king.

One carving in particular, on the lid of the sarcophagus, has inspired endless speculation. It shows Pakal seated in the middle of the picture. Below him is a representation of the Mayan underworld, Xibalbá. A tree emerges from Pakal’s body, which connects him to the cosmos. But ancient alien theorists - yup, they do exist - believe the image should be looked at sideways, and actually shows Pakal travelling through space, his hands on the controls of a spaceship.

These theorists believe Pakal was one of a race of aliens from outer space, who came to earth to bestow their advanced knowledge of mathematics, building and time-keeping upon the Maya. Another theory about Pakal is that he is a time traveller, who went back in time to teach his descendants. This is based upon the fact that his skeleton measures 1.70 metres, while most Mayans are much shorter.

The Mayans had an intricate and sophisticated system of marking time, developed through centuries’-long observations of the solar and lunar cycles. It consists of three separate calendars: the 260-day tzolkin, a calendar used to schedule religious events; a 365-day civil calendar known as haab; and the bak’tun or ‘long count’, which marks longer cycles of time, of around 5,125 years.

December 21st, 2012 was when the 13th bak’tun came to an end. You may recall that this was when some of your more new age friends thought that the world was going to end.

Palenque is a state of mind. Palenque will always be the way that you reflect it

The person who popularised this belief was José Argüelles. He suggested that 2012 would be a year of destruction and upheaval, and the world as we knew it would end on December 21st. He said he had heard this message while standing in the Temple of Inscriptions at Palenque, via a prophecy delivered to him by King Pakal through a stone tube from his crypt (an architectural feature which does exist). His thoughts of Armageddon caught on, feeding into contemporary anxieties about climate change and nuclear war.

Spoiler alert - the world didn’t end on December 21st 2012, much to the surprise of the hundreds of new age spiritualists who had gathered at Palenque, ready to chant their way towards Armageddon.

But although Palenque’s first tour guide and Maya expert Moises Morales rubbished these end-of-the-world theories, he did admit there was something special about Palenque, something that caused people to return time and time again.

“Palenque is a magic mirror, Palenque reflects you. If you are miserable, you will see miserable Palenque. If you are a poet, you will see a poetic Palenque. Palenque is a state of mind. Palenque will always be the way that you reflect it,” he said in an interview.

“I loved the people who were falling in love with Palenque, who were crying in front of the Temple of the Foliated Cross. They didn’t know why it drew their tears, but it touched them deeply.”

Inspired? Check out our Mexico Adventures and our other trips in Central America.