Being by the sea and listening to the gentle sound of waves is often considered to be restorative. ‘Blue mind’ is the term used to describe the peaceful, meditative state that being beside the water evokes. There are plenty of studies - and enthusiastic social media posts - about the mental and physical benefits of cold water swimming. But not everyone feels this way. There is an entire array of phobias and fears associated with water.

Thalassophobia is a fear of the ocean and other large bodies of water. Bathophobia is a fear of deep water. Cymophobia is a fear of waves. And aquaphobia is a fear of seeing (or even thinking) about water, from rivers to swimming pools and even drinking water.

“Some people have aquaphobia so intense that they can’t even drive over a body of water on a bridge without having a panic attack. Some people won't have showers because they can’t bear the water over their faces - and those are both real examples,” explains Joanna Lay, an aquaphobia coach.

Many of us feel a ripple of disquiet when something brushes against our legs while we’re swimming outdoors

While severe aquaphobia might be relatively uncommon, many of us feel a ripple of disquiet when something brushes against our legs while we’re swimming outdoors. In fact, the 2022 Chapman Survey of American Fears found that 28.7% of people surveyed had a fear of deep lakes and oceans (it ranked higher than being stalked, fear of flying or arachnophobia).

What is the origin of these water-based fears? Is there anything we can do to overcome them? To find out these answers to these questions we spoke to aquaphobia coach Joanna Lay and Dani Cameron, who transitioned from the pool to open water swimming seven years ago, and has never looked back - despite her fears.

Into the Depths: The Origins of Our Fear of Water

Joanna is a ‘yes’ person, which is why she swapped a career in the police force to go into business with her children’s swimming teacher. She now owns GR Swimming School - affiliated with the Institute of Aquaphobia - and is one of the few advanced aquaphobia coaches in the UK. According to Joanna, a fear of water is far more pervasive than you might think. It’s partly due to a lack of exposure - a recent survey by Swim England suggested that 14 million UK adults (around 1 in 3) can’t swim the length of a 25 metre pool.

“There’s so many factors that lead to aquaphobia,” Joanna says. “It can be demographic - back in the day, if you didn't live near the sea, why have swimming lessons? Those people didn't know how to swim because it wasn't thought necessary. Then they have children, and because they don't know how to swim, they want their children to stay away from the water to protect them. The kid picks up on their parents’ worries about water, and stays away from it as well. The fear increases and then it becomes a phobia.

“Then you've got financial factors. People might have been able to afford lessons when they were young. Times are hard. And you've got people who experienced something really bad. A lot of people say that during school swimming lessons they were just pushed in, straight to the bottom. Some people had to be rescued.”

A lot of people say that during school swimming lessons they were just pushed in, straight to the bottom. Some people had to be rescued

Alongside this, there are the fears associated with swimming in open water. Of shark attacks, jellyfish stings; of getting caught in the weeds of a river. These are fears that Dani Cameron says she used to have in abundance when she started swimming outdoors.

Dani’s mother moved to the UK from Mauritius, and like many islanders, never learned to swim. But she made sure that Dani had swimming lessons as a child. It was only in adulthood, following her mother’s death, that Dani decided to try open water swimming.

“For my birthday I got a wetsuit and we went to a nearby swimming lake,” she says. “It actually wasn’t that good because it’s very green water. In a pool you can see everything; there’s lines you can follow and you know when you get to the end. Whereas this was just green, and somebody had told me there were bodies in there. There aren’t - I think the rumour is something to do with the end of World War II, when they dumped a lot of tanks in there.

“Afterwards, I was having a bit of a whimper, and somebody told me I should try swimming at the beach, I might enjoy it. Because the sea is much more alive. I went to the beach and I haven’t stopped going in the past seven years. Even so, I used to be afraid of everything. Everything that lives in there. Stuff that’s accidentally got in there or been dumped in there. Anything that touched me I had to rationalise down to a plastic bag, so I could get on with my swim and worry about it later.

“I still worry about things that will probably never happen, like swimming into dead bodies. It’s the touch; putting your hand out and not being able to see. When we were in Dover a couple of weekends ago, I put my hand into something and I realised I remembered the sensation from doing Jersey to France. A jellyfish. They feel really weird, how I imagine a breast implant to feel. Harder than you would think, like you would have to put a lot of pressure on it for it to burst. But I didn’t freak out because I remembered the feeling.”

Even Joanna, whose career is devoted to helping people overcome their aquaphobia, confesses to a mild bathophobia.

“I'm okay in a swimming pool and I'm okay in the sea. But once we start talking about open water, you get the ‘what ifs’. I watch horror films every Thursday night with my daughter,” she says.

I still worry about things that will probably never happen, like swimming into dead bodies. It’s the touch; putting your hand out and not being able to see.

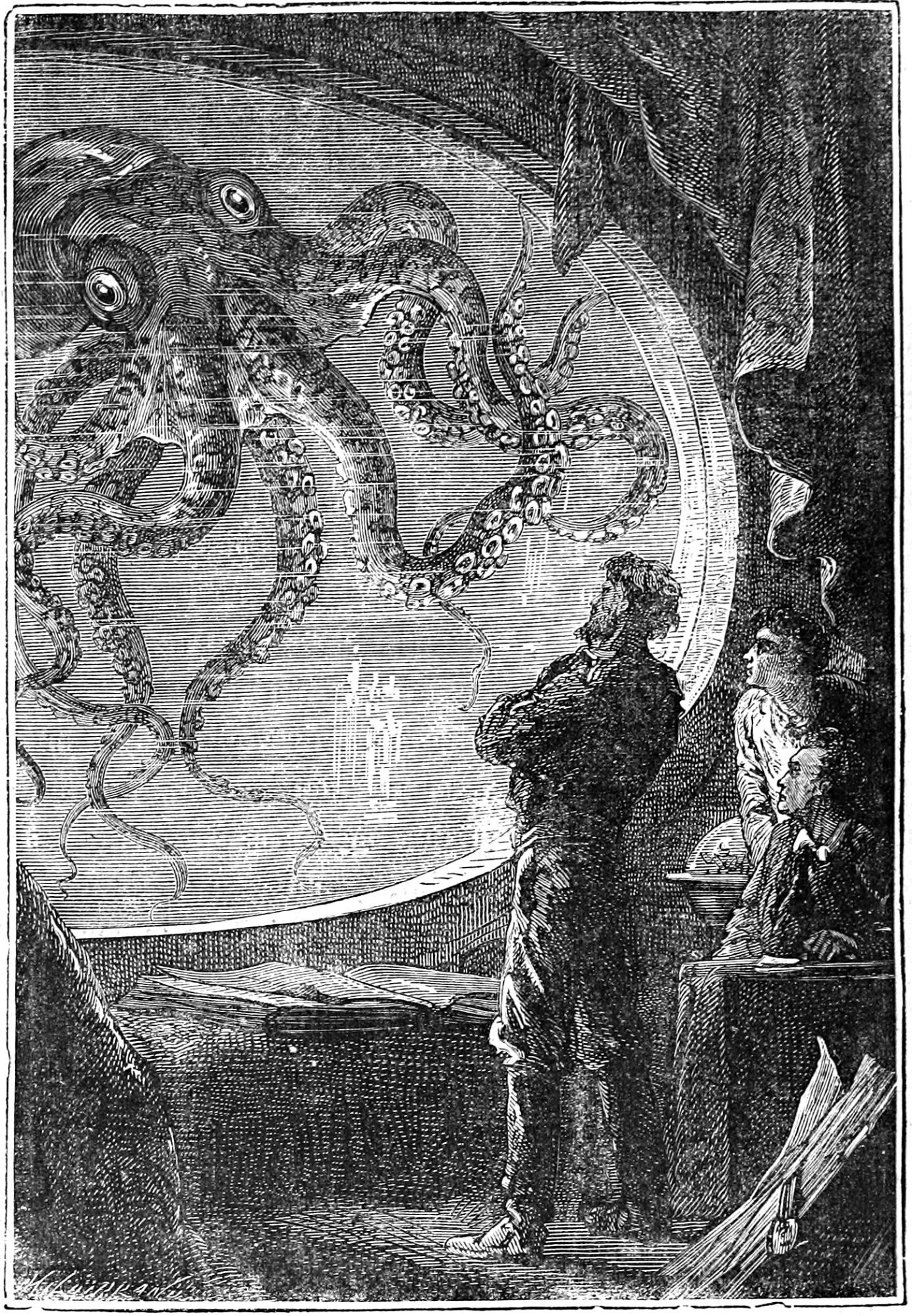

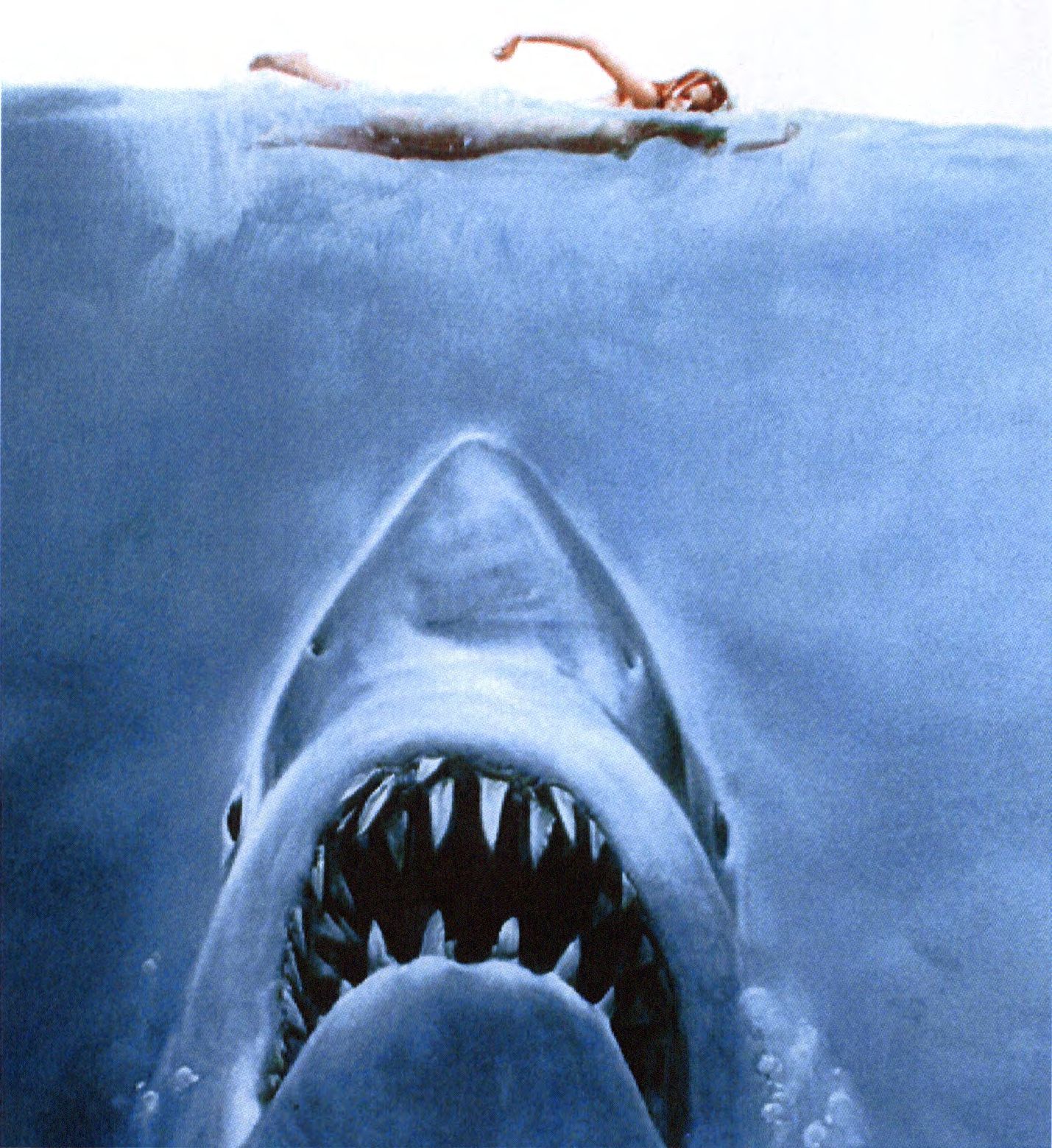

Both Joanna and Dani mention the film Jaws in the course of our conversation - a shark attack horror film which coined the term ‘the Jaws effect’ - the negative portrayal of sharks and fear of swimming in the sea caused by the film. And Jaws is far from the only one: our culture is pervaded by images, stories, films and myths of aquatic horror. The work of writers such as H. P. Lovecraft and Jules Verne paint vivid images of monsters lurking in the deepest recesses of the ocean.

“With only a slight churning to mark its rise to the surface, the thing slid into view above the dark waters. Vast, Polyphemus-like, and loathsome, it darted like a stupendous monster of nightmares to the monolith, about which it flung its gigantic scaly arms, the while it bowed its hideous head and gave vent to certain measured sounds,” Lovecraft writes in his short story Dagon.

It’s not just our contemporary culture that contains such images. Each seafaring culture has its monsters. Greek mythology is full of tales of the dangers of the sea, from whirlpools to shipwrecks and the many-headed Hydra. Inuit mythology tells of the Qallupilluit, creatures who live under ice floes and steal children wandering too close to the water. If we look at religious and mythical cosmologies, dry land is associated with comfort, security, abundance and safety, while the sea is associated with chaos, danger and being lost. A fear of water isn’t just something our families teach us - it’s part of a collective cultural unconscious.

This fear is partly rooted in fact. Going to sea is perilous, especially in the days before sophisticated navigation and boat building techniques were developed. But as any swimmer will know, ‘The Fear’ isn’t always rational - an image of being pulled under the water by an unknown creature can visit you even in places you swim at regularly.

The unknowable depths of the sea pose a problem for the consciousness; they reflect our fear of what is beyond the limits of our comprehension

“The unknowable depths of the sea pose a problem for the consciousness; they reflect our fear of what is beyond the limits of our comprehension,’ Seán Harrington, an academic who researches nautical horror, writes in Beasts of the Deep.

The sea is ‘other’ - its vastness and its fluidity is difficult for us to comprehend, which is why it evokes such strong reactions. Because we can't see the bottom of the water, we fill the darkness with imaginary monsters and menacing shadows.

Overcoming a Fear of Water

Joanna has helped many adults and children overcome a fear of water, and recommends using the Institute of Aquaphobia’s Coaches Global Map Finder to find a coach. Her lessons take place in a swimming pool, but they aren’t about learning how to swim - the aim is to help change people’s relationship with water. The first step is to determine how aquaphobic someone is by doing an assessment. The next step is to make them feel comfortable in a pool-based environment.

“They're going into a situation that's alien to them, that they're scared of, so they've got no control over what's going to happen,” Joanna says. “We basically turn that around. Before I get in the pool with them, I get them to step up and down on the poolside. I tell them that what they can feel is hard, and I tell them the bottom of the pool floor is exactly the same, and they’ll be able to stand up. That's something I keep reiterating.

I tell them that while you need to treat water with respect, it's a lot of fun

“The first thing we have to do is show them how to get in and get out of the pool safely, telling them how to use the ladders, that it's like being on an ordinary ladder, three points, contact, slide your hands down. And making them know they are in control of every single step down that ladder. I tell them that they are in control of what they are going to do in the water - that they aren’t going to be pushed.

“I will also explain that when you're on holiday somewhere and there is a pool, there's plenty of signs around it to help you to be safe like ‘shallow end’, ‘deep end’. You might even see a sign of someone diving with a line through it. Common sense would dictate that there's a reason why they've done that, it’s likely it’s too shallow. I tell them that while you need to treat water with respect, it's a lot of fun.”

Joanna’s aquaphobia lessons are intended to show that the pool is a controlled environment, where people will be safe. But what of the ocean, or the river, where the watery environment is less predictable? Although it might be more complex, water in rivers and seas can be ‘read’ - you can learn to spot the direction a river flows in, or spot a riptide under the ocean’s surface.

“Knowing where you’re swimming is really important. When we’re on the beach, we stand there for about twenty minutes just watching the sea. We try to work out which way it’s running, if there’s any debris in the water,” Dani says.

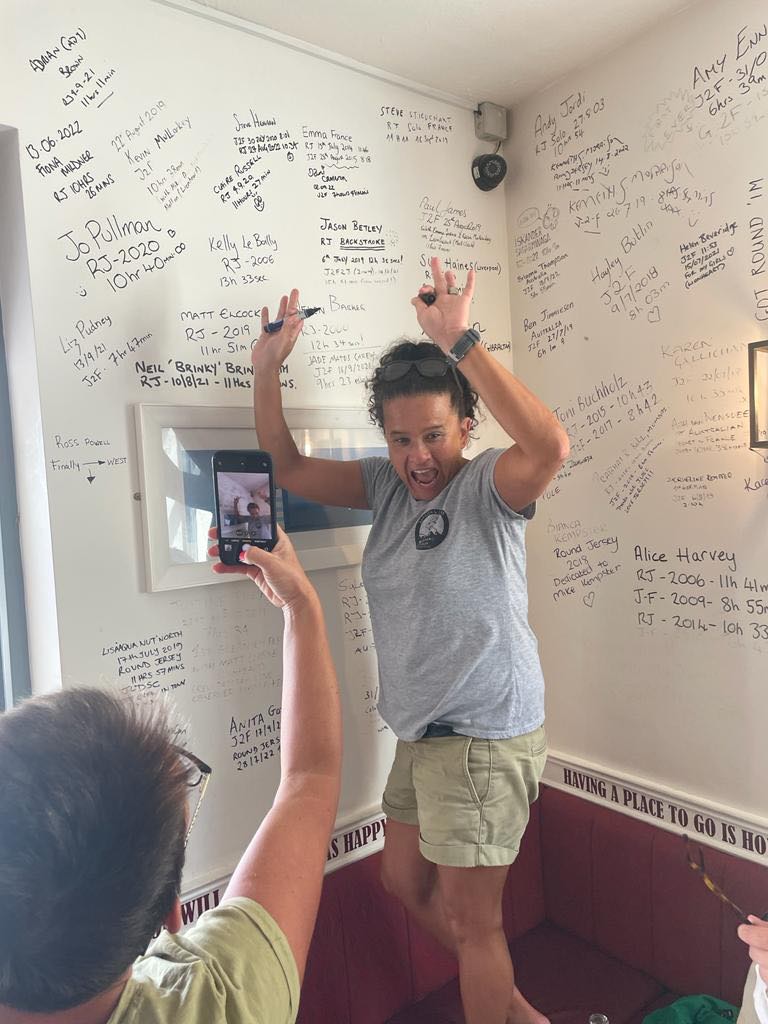

Over the past couple of years, she has increased in confidence swimming outdoors. She swam in Ullswater, in the Lake District, competed in an English Channel relay and swam from Jersey to France. This September, she’ll be attempting to swim the length of the English Channel.

“Now, I’m far less scared of things in the water,” she says. “Now, what I’m scared of is failure. The shame attached to the fact that you didn’t get across. I’ve come from nowhere, and I’ve worked really hard, and I’ve given up loads of stuff. There’s a lot of investment in it. It’s so much time, and so much money. As far as I know, very few mixed-race women have swum the channel, so I want to succeed.”

I ask Dani how she went about overcoming her fears of water. For the first few years, she says, she closed her eyes when swimming because she was worried about what she might see.

“Last year I went to Ireland on a swim camp, to Sandycove in Kinsale. It’s really lovely, but one side is the Atlantic, and when you try and navigate out you’ve got to go through these really sharp, horrible rocks. There’s a lot of kelp. So you had to have your eyes open, and I was like, 'what the fuck?' There were huge spider crabs the size of my head, jellyfish, and dangerous rocks. But doing that camp knocked a lot of the fear on the head. The only thing that I still find quite difficult are seals.”

You can scream in the water, just let out a blast. Sometimes you need to just release it

In the early days, she was prone to letting out a shriek when something brushed against her.

“Then someone said to me that you spoil a good swim by screaming, because your fear transplants into other people,” she says. “Now I have to be very considered when I scream - you can scream in the water, just let out a blast. Sometimes you need to just release it.”

The more time she spends in the water, and the more knowledge she gains of the environment, the more her fears diminish.

“The dark shadows you can rationalise quite quickly because they’re either you or the boat. If the sun is over the top of you, anything that’s there for a long time is going to be you. Anything that’s fleeting is likely to be a seal or a dolphin,” she says.” But if I get scared, I do also have a word with myself. I tell myself ‘you’ve swam here for seven years, and you aren’t dead yet.’”

You do what the sea wants you to do. It’s moving all the time.

Dani also recommends that people try wild swimming in a small group for the first time, with someone knowledgeable to guide them.

"You need to go with people who know what they’re doing. Because the lakes and the rivers are totally different to the sea," she says. "It’s not about finding a tribe. It’s just about finding people who will look after you. I wouldn’t swim on my own. You could have a heart attack. You might get cramp."

I'm curious why Dani prefers swimming outdoors to in the pool, considering her fears.

“It’s just a better swim outdoors,” she says. “It’s a harder swim - you’re either swimming against the tide or with it. It’s very much on the sea’s terms. You can’t go in thinking you are going to swim for a certain amount of time, or do a certain number of lengths. You do what the sea wants you to do. It’s moving all the time. So no swim is like the day before - it’s more tactical than swimming in a pool.”

“And it’s good for my mental health, too. When I started there was a lot of tragedy in my life I was reeling from, and I have lots of other responsibilities too. But when you get in the water, all that fades away - and worrying about a seal is much easier to deal with than that.”

Inspired? Take the plunge on our inclusive, small-group wild swimming adventures.