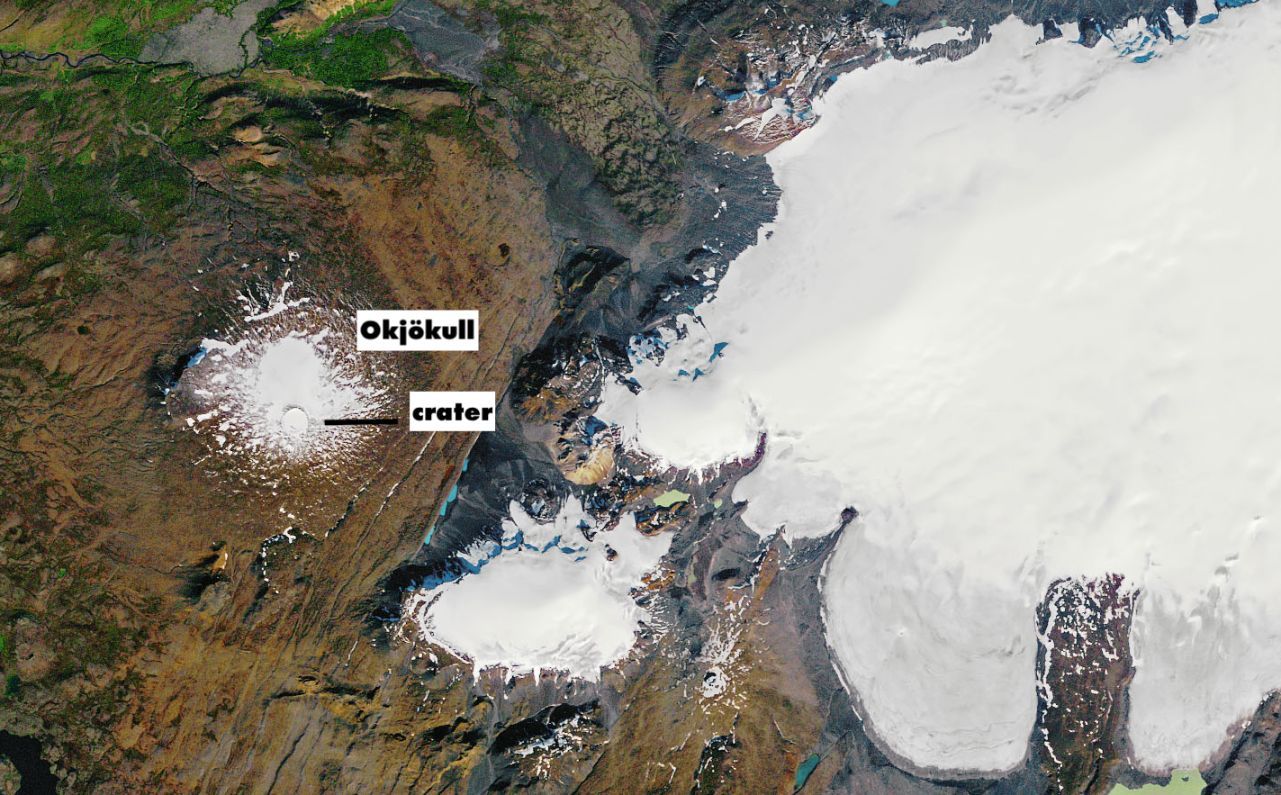

As late as the early 1900s the Okjökull glacier covered 15 square kilometres of mountainside in western Iceland, sitting at the top of the shield volcano ‘Ok’. In 2019, the glacier became the first of Iceland’s hundreds of glaciers to disappear due to climate change. Today, there is no Okjökull glacier - but there is an Okjökull remembrance plaque.

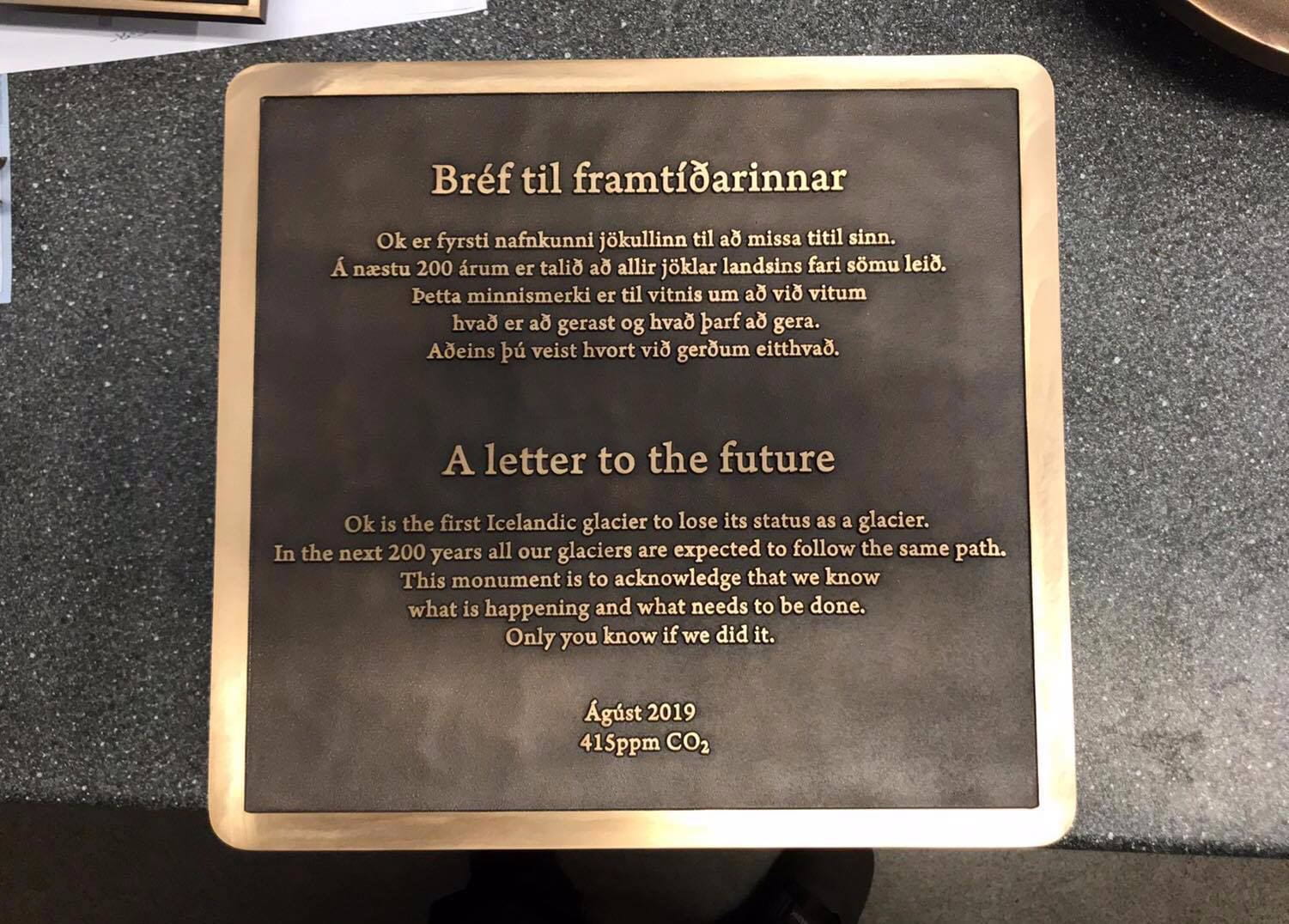

At the co-ordinates of N 64°35.498' W 020°52.253', mounted on a rock 1,114m above sea level, the Okjökull plaque contains a “Letter to the Future”. Written by the Icelandic novelist, playwright and poet Andri Snær Magnason, the plaque is a sombre reminder of our collective responsibility to look after the Earth. It reads:

“Ok is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier. In the next 200 years all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path. This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.”

Beneath the message? The date “Ágúst 2019” and the statistic 415 ppm CO2 - the global atmospheric carbon dioxide reading for that month. It was in May 2019, just two months before this, that atmospheric CO2 levels exceeded 415 ppm (parts per million) for the first time in human history.

This is a story that shows climate change is not a future problem. It is here today, and is already writing our history. This is the story of how Okjökull disappeared.

The “Little Ice Age” (a term coined by geologist François E. Matthes in 1939) came to an end just before the beginning of the 20th century. It was a prolonged period of regional cooling, particularly felt in the North Atlantic, that took place over hundreds of years - from around 1300 to 1890. During this time period, there were no glacial disappearances. Quite the opposite in fact - there were glacial advances. At the end of the Little Ice Age glaciers began to decline.

An increasingly clear picture of glacier mass loss around the world has been appearing. Glacier mass loss is a global phenomenon, and the rates in the early 21st century are unprecedented for the observed period.

This fact, in and of itself, isn’t particularly alarming. Glaciers advance and retreat as the world has cycled through cold and warm periods. What is significantly more alarming is the exponential increase in the rate of acceleration of glacier melt as the 20th century has drawn on. According to research from the University of Iceland (November, 2020), almost half of the total ice mass lost in Iceland in the last 130 years has occurred since the mid 1990s - with climate change the only plausible reason for such a significant rise in the melt rate.

The university's research states: “Glaciers in most areas of the world are losing mass as global temperatures rise in response to increased greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. But with the aid of satellite and other remote-sensing data, an increasingly clear picture of glacier mass loss around the world has been appearing. Glacier mass loss is a global phenomenon, and the rates in the early 21st century are unprecedented for the observed period.”

Glaciers are important. They impact weather patterns. They shape what lives, where it lives and what sort of land it lives on. How often have you visited a national park or even a now-populous city and heard about how the landscape was shaped by glaciers millions of years ago? Their decline is a warning.

A glacier can only die after a period of terminal decline lasting around a decade. Every year in winter, snow usually falls on a glacier, topping it up. In Iceland, glaciers make up 10% of the landscape (it's in the name, really) - and they feature heavily in literature, schooling, and local legends, myths and nursery rhymes.

The Okjökull had been declining for years before it disappeared. At its largest, near the end of the 19th century, it was sixteen square kilometres. By 1978, it was three square kilometres, and in 2014, Iceland’s leading geologist Oddue Sigurðsson visited, found only slush, and declared that the glacier was dead.

“It’s a very small glacier,” glaciologist Ruth Mottram, whose work primarily centres on the Greenland ice sheet, told the BBC, on the impact of Ok’s loss. “These small glaciers can be quite responsive to climate change and to changes in the local conditions and they can disappear quite rapidly. So in that sense, it’s sort of a warning that this is coming for us.”

At the time that Okjökull was pronounced dead, anthropologists Cymene Howe and Dominic Boyer, of Rice University, were conducting field work on the social impacts of the climate crisis in Iceland. They made a documentary about the death of Ok glacier - aptly called “Not Ok” - and after it premiered in 2018, they came up with the idea of the memorial plaque. They asked Andri Magnason to write the plaque, and on Monday 19 August, 2019, around 100 people climbed the two hours, to the top of the shield volcano ‘Ok’, to where there was once a glacier.

“On top of the mountain instead of the glacier is a lake now,” Andri Snær Magnason told the BBC. “It was never meant to be a lake [...] but now this lake is like a blue eye, looking into the sky from this mountain top.”

The ceremony was was lead by researchers from Rice University, as well as Magnason, and the geologist Oddue Sigurðsson. Amongst the attendees were also Katrín Jakobsdóttir, the Prime Minister of Iceland; Guðmundur Ingi Guðbrandsson, the Environment Minister; and Mary Robinson, the former President of Ireland and U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Memorials are not for the dead. They are for the living. We want to underscore that it is up to us, the living, to respond to the rapid loss of glacier and the ongoing impacts of climate change.

“The climate crisis is already here,” Katrín Jakobsdóttir told the crowd. “The time has come not for words, not necessarily for declarations, but for action.”

“It was strange to imagine that where you were standing, there used to be fifty metres of snow," said Magnason. "It’s a beautiful mountain still - but we can’t fall for the illusion of the beauty. This is something that you shouldn’t be seeing."

The plaque, and lake, stand as a monument to climate change, and a warning of what we can and will lose on a grander scale if we continue to pollute our world.

“Memorials are not for the dead,” said Cymene Howe, of Rice University. “They are for the living. We want to underscore that it is up to us, the living, to respond to the rapid loss of glacier and the ongoing impacts of climate change. For Ok glacier it is already too late.”

Inspired? Read the Glasgow Declaration from 'Tourism Declares a Climate Emergency', or check out our adventures in Iceland.