In January 1943, three Italian prisoners of war escaped from British P.O.W Camp 354, near Nanyuki, Kenya. Their names were Felice Benuzzi, Dr. Giovanni 'Giuàn' Balletto and Vincenzo 'Enzo' Barsotti. Their goal? Freedom, of course, but not in the sense that you might expect.

The trio had broken out of confinement with a singular aim: to climb to the summit of Mount Kenya, the 5,199m (17,058ft) mountain which overlooked their camp, and which Benuzzi had become fixated on to avoid losing his mind to monotony. Over the coming 18 days, the prisoners climbed the mountain, using makeshift equipment and hoarded rations. Then - with nowhere else to go - they broke back into P.O.W Camp 354 and handed themselves in to commandants.

Their only view of the mountain from the south was found on a tin of Kenylon condensed beef...

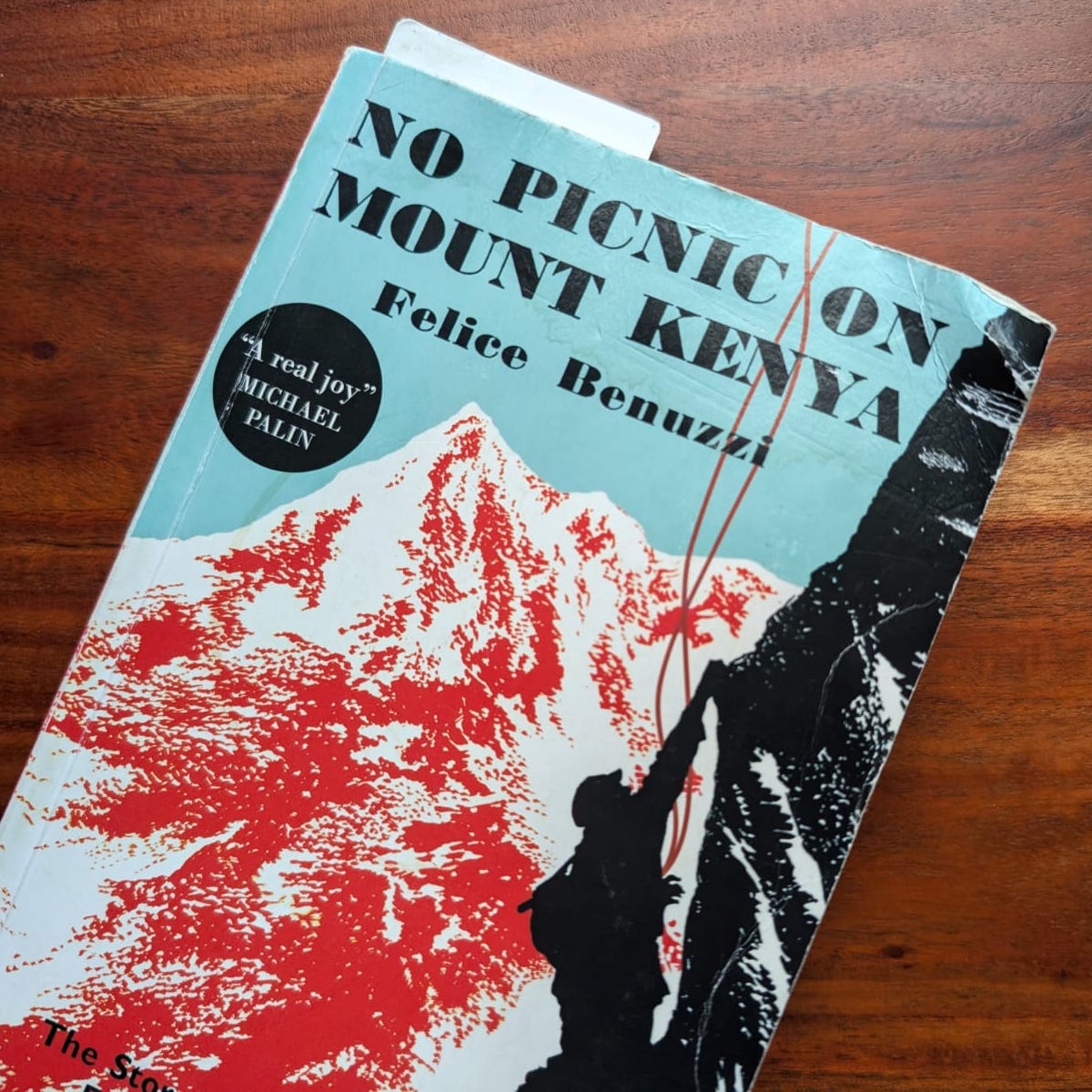

Through Benuzzi’s classic account, No Picnic on Mount Kenya, written in P.O.W camps in the following years, nearly every detail of this dramatic feat is known.

Felice Benuzzi was born in Vienna in 1910. He grew up in Trieste, climbing in the Julian Alps and the Dolomites, studied law at Rome University and represented Italy as a swimmer at international level. In 1938, Felice married a Jewish woman, Stefania, just before racial laws were introduced in Italy which forbid such unions. These laws led the couple to move to Ethiopia - which was occupied by Italy at the time, but where these rules didn’t apply.

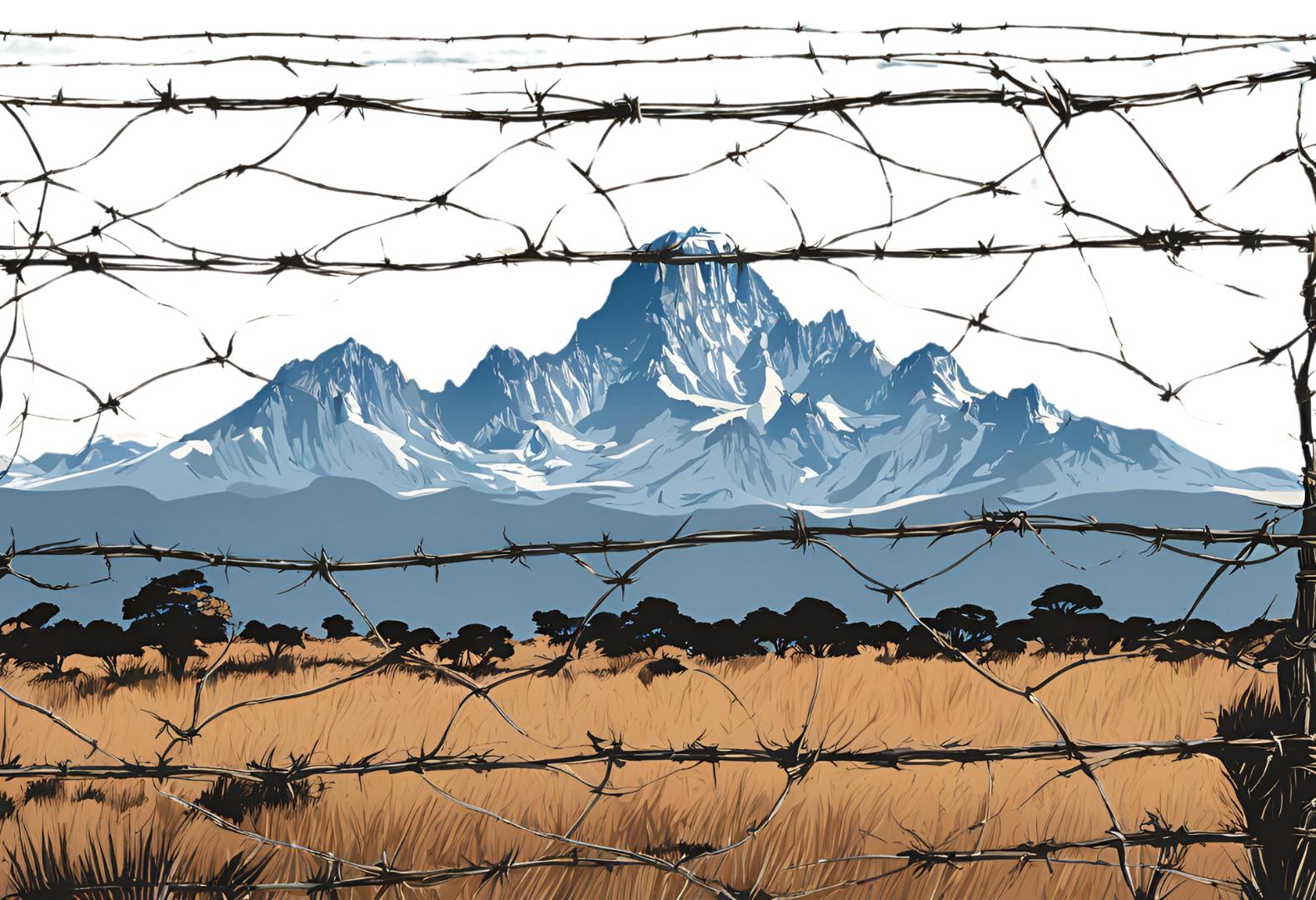

Italy had invaded and occupied Ethiopia in 1935, but in the spring of 1941, during World War Two, the British overran the Italians in the region, and Benuzzi, a colonial administrator, found himself imprisoned in a P.O.W camp in Kenya. Life in this camp, which could hold 10,000 prisoners, was tedious. “There was no vegetation to conceal or in any way soften the crudeness of the barbed wire fences,” Benuzzi wrote. “People in prison camps do not live. They only vegetate.”

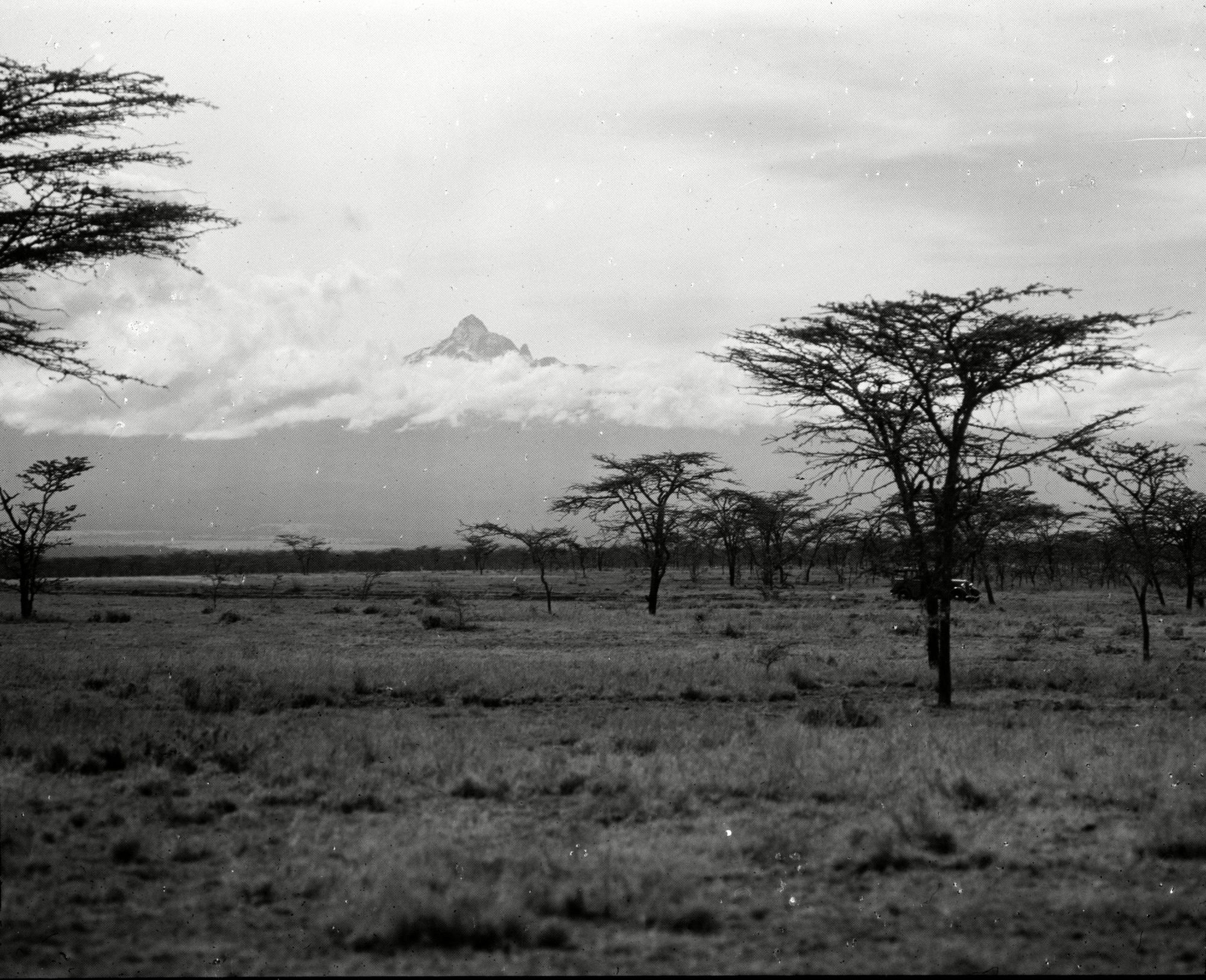

After a year, Benuzzi was transferred to Camp 354, near Nanyuki, in the centre of the country. The camp was at the foot of Africa’s second highest summit, Mount Kenya. Amongst the clouds of the rainy season, the summit soon revealed itself.

“An ethereal mountain emerging from a tossing sea of clouds, framed between two dark barracks," Benuzzi described. "A massive blue-black tooth of sheer rock, inlaid with azure glaciers; austere yet floating fairy-like on the near horizon." It was the first 5,000m (16,404ft) peak he had seen. "I had definitely fallen in love.”

The sound of another prisoner using a hammer soon gave Benuzzi an epiphany. “For him, the future existed because presumably he meant to finish his job,” he wrote. This prisoner had, Felice realised, found a remedy against captivity. “The future exists if you know how to make it." The white glaciers of Mount Kenya gleamed with mysterious light. "A thought crossed my numbed mind like a flash.”

Escaping Camp 354 to reach neutral territory and true freedom was all but impossible, but for the first time since he was imprisoned, Felice Benuzzi felt he had a purpose once more. “I shall stage a break in this awful travesty of life,” he wrote. “I shall try to get out, climb Mount Kenya, and return here.”

Benuzzi set out to find two companions to come with him, one of whom would scale the mountain with him, and another who could stay at base camp.

There was an alpinist with several first ascents in the Alps to his name in camp, but he wrote off the endeavour as “sheer madness.” In Dr. Giuàn Balletto, Felice found his second mountaineer, and the duo swiftly set about preparing (Enzo Barsotti, a sailor and the third man - described as “a fairly good bridge player and a very heavy smoker” - wouldn’t join the party until a week before departure).

Ice axes were cold forged from hammers nicked from camp stores. Crampons were made using old car parts and barbed wire.

A bed-net was unknotted and turned into a sisal climbing rope. Ice axes were cold forged from hammers nicked from camp stores. Crampons were made using old car parts and barbed wire. “It was very appropriate,” wrote Benuzzi. “That the same barbed-wire fences that enclosed us should provide material to be used during our escape.” The duo cut ax-handles to double as tent pegs, made a patchwork Italian flag, borrowed binoculars and hoarded their rations.

The group would meet at night to analyse maps they found in a book by an Italian priest. Their only view of the mountain from the south was found on a tin of Kenylon condensed beef, a new ration in camp. “We were disappointed to see that the peaks looked just as formidable from this new viewpoint,” Felice wrote.

It took eight months to prepare. On 24 January 1943 the day of escape came.

“It was not very difficult to escape from a P.O.W camp in East Africa,” Benuzzi wrote. “Far easier, probably than any camp in Europe.” The reason was that there was nowhere to go when you got out. In the event, the trio of prisoners forged a key and left through the vegetable gardens at night.

The early stages involved passing through grassland, avoiding military patrols and marching through dense forest. The wildlife stunned them - “graceful sunbirds with slender beaks and bright colours", "troops of monkeys jumped from branch to branch", "butterflies of every size and colour.”

A leopard was scared off with pots and pans. The group hid from a rhino scratching on a tree, and a watering hole was shared with a “magnificent, solitary bull elephant”. Bennuzi wrote: “No other creature, I thought, could represent in such a perfect way the strength, the dignity, the gravity and majesty of creation.”

The group encountered waterfalls and a "veritable botanical garden" of flora. They followed a stream; taking nine days to reach the base of the mountain, through bamboo thickets and tussock grass today traversed by four-wheel drive.

Soon, the trio emerged out of the trees to heather and open alps, where the sun lit up the rock formations, reminding Benuzzi of the Dolomites back home.

Passing their first lanky lobelia plants, perhaps the most iconic vegetation on the mountain, Felice struggled with altitude sickness, but pressed on. On Monday 1 February, Batian, the highest peak on Mount Kenya, came into view - “so near, so beautiful, so tantalising [...] its appalling north face armoured with ice, its jagged pinnacles not yet touched by the rising sun, dreamlike, overwhelming”.

As mist blinded their view, and a “whirling blizzard” froze their hands, the pair found themselves trapped on a sheer cliff face...

Their base camp was eventually established around 4,267m (14,000ft), lower than had originally been planned due to Enzo's collapse. The sailor was brought back around with some coffee, but he could climb no higher on the mountain.

It was from here that Felice and Giuàn pressed on to the peak; to rope climb their way up Batian, or failing that, to reach Point Lenana, a slightly lower peak at 4,985m (16,354ft). Benuzzi describes the “fairy architecture of pinnacles, ridges, points, buttresses, jagged peaks and ledges, bejewelled with sprinkled ice, blushed at last with rose."

Reflecting on this high, glacial scene he continues: “our eyes had feasted on unforgettable scenes to compensate us for what our mouths had lacked.”

It was before 3am on Thursday 4 February that the duo set off for the “black and threatening” Batian. By 8am, they were traversing the north face of Dutton Peak (4,865m/15,961ft), after putting their ice axes to work in the frozen couloirs.

The standard route up Batian is graded Hard Severe, but the Italian duo did not find it, instead taking on the north-west ridge up the mountain, on a route which had been branded “hopeless” by Shipton and Tilman 13 years earlier.

As mist blinded their view, and a “whirling blizzard” froze their hands, the pair found themselves trapped on a sheer cliff face, unable to find the next move on what could easily have been a fatal mountaineering pitch. In the end, they only just escaped back off the climbing wall with their lives - at times hallucinating and sobbing on the retreat. Near frozen, they collapsed into their tents defeated.

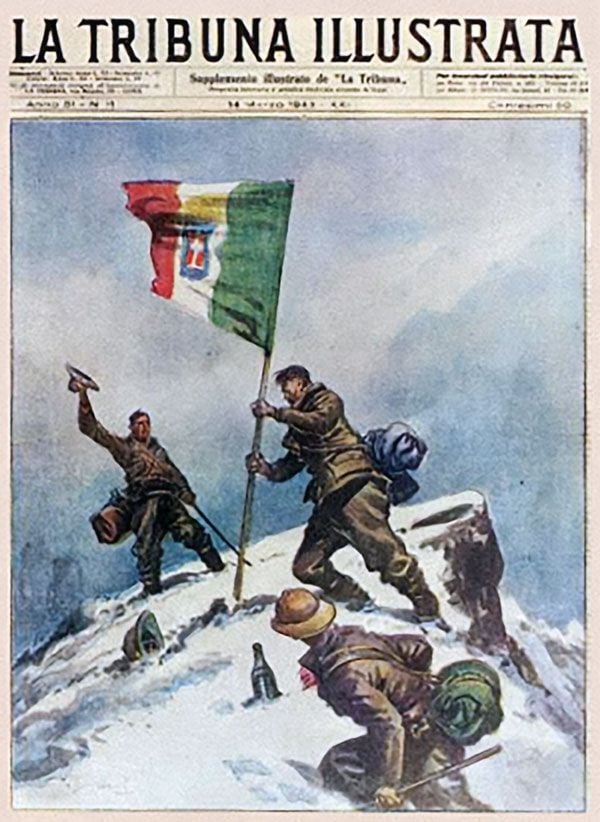

Despite being all but out of rations - thin strips of meat extract (Bovril) on broken biscuits being their main meal - a day of rest was had, before the pair regrouped and headed up the mountain again, this time to plant their flag on Point Lenana.

“It looked imposing,” wrote Felice. “A violet-black rock perched on a bright white ice dome.” They set off at 1am, and at 8am, they reached the ridge of Lenana.

"A seemingly boiling sea of clouds cloaked the plains," wrote Benuzzi. "Perhaps no painter in the world could reproduce this.” At 10.05am, they reached the peak. “A great peace hung over the broad expanse. Under the dark velvety sky the wonderful scenery of the country at our feet had a strange radiance. This was the climax of eight months’ preparation and of two weeks of toil. It was worth both.”

As a reward for their “sporting effort”, the Commandant shortened their 28 days in solitary confinement to seven...

They hoisted their flag on the summit (it was discovered just one week later, and is now in the Museo della Montagna, Torino), left their names at the peak in an empty brandy bottle, and arrived back at base camp to the embrace of Enzo.

Climbing gear was left on the mountain to lighten packs for the three-day descent. The trio had only a few grains of rice left to eat on the journey. “Every step would bring us nearer to food, but nearer also to captivity,” wrote Felice.

The climbers arrived back at P.O.W Camp 354 on Wednesday 10 February, broke back in through the gardens, ate “in one afternoon enough food to compensate for the meals we had missed in the past week” and, after a good night's sleep and a change of clothes, handed themselves into the Camp Commandant.

As a reward for their “sporting effort”, the Commandant shortened their 28 days in solitary confinement to seven. With reading material smuggled in to the trio, as well as extra food rations and supplies of cigarettes, Benuzzi joked: “the memory of those seven days in the cells is almost as pleasant a recollection as that of our trip on the mountain.” The cell window looked out onto Mount Kenya.

Benuzzi wrote his account of his climb up Mount Kenya, a story of humour, heaven, hell and humanity, in Italian and English while still in P.O.W camps.

The Italian was repatriated in August 1946, and entered the Italian Diplomatic Service in 1948. He served in Paris, Brisbane, Karachi, Canberra, West Berlin, and as the Head of Delegation for Italy at the United Nations, before being appointment ambassador in Montevideo, Uruguay in 1973. He retired to Rome, and in retirement, served as Head of the Italian Delegation for the Antarctic.

Inspired? Climb to Point Lenana on Mount Kenya on a group adventure!