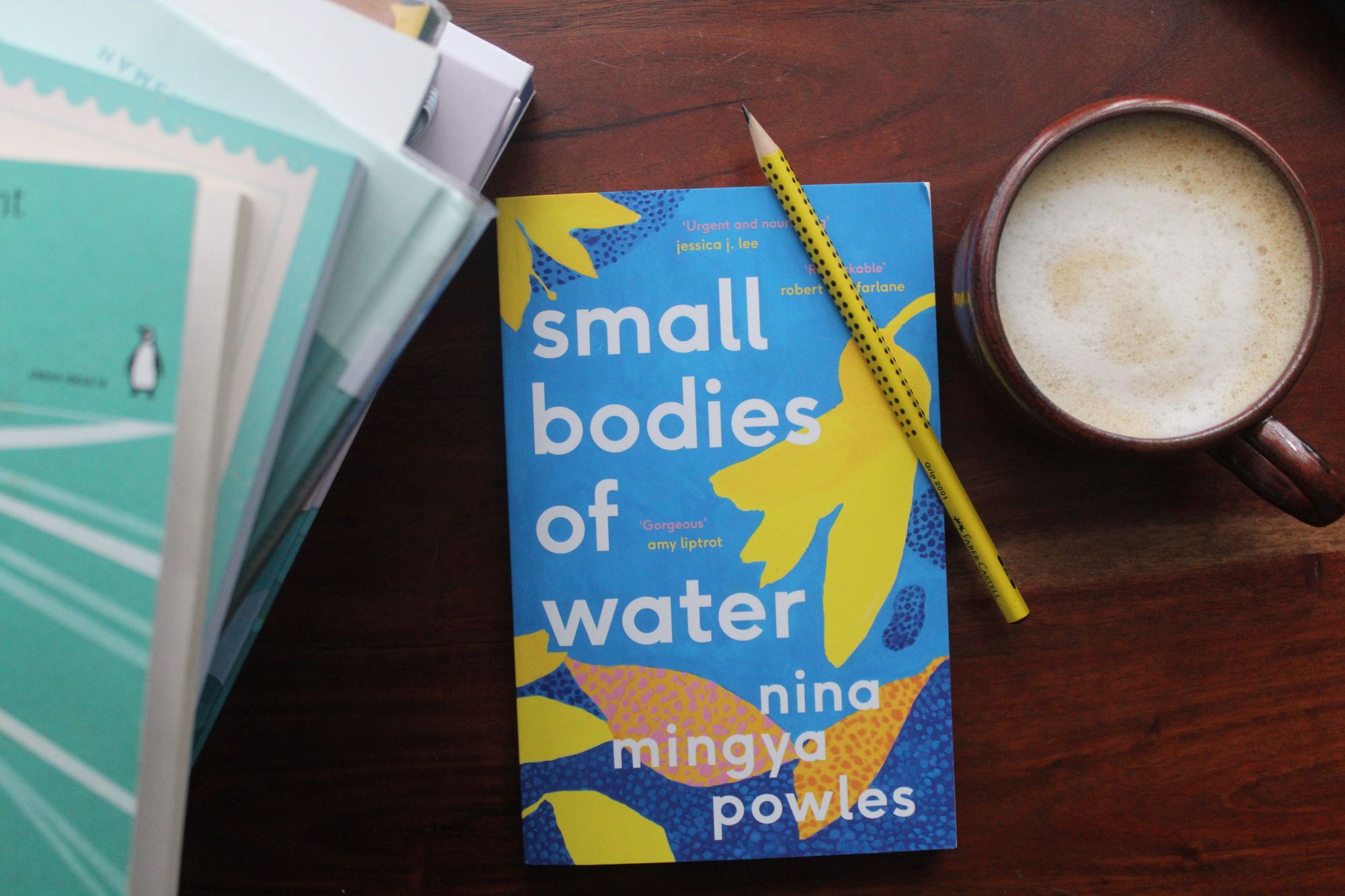

Nina Mingya Powles’ Small Bodies of Water is a lyrical collection of essays that seamlessly blends nature writing with dreams, childhood memories and everything from earthquakes to the ancient lunar calendar.

Powles is white and Malaysian Chinese; she’s lived in New Zealand, Shanghai and London. “Home was a slippery word,” she writes in the first essay of the collection, 'A Girl Swimming is a Body of Water'. In this essay, she reminisces about different places she has swum in over the years - a swimming pool in Shanghai, Wellington Harbour, the ladies’ swimming pond at Hampstead Heath.

“Where is the place your body is anchored? Which body of water is yours? Is it that I’ve anchored myself in too many places at once, or nowhere at all? The answer lies somewhere between. Over time, springing up from the in-between space, new islands form,” she writes.

These questions of home and identity ripple through each essay in the collection. In 'A Girl Swimming is a Body of Water', we see that Powles tries to acclimatise to new environments through the act of swimming. Water is a space of connection, both with herself and the outside world: “it contains all the places I call home, as well as all my memories, and all my names.”

But if water embodies connection, the concept of ‘home’ is elusive and fragmented.

“Home is not a place but a collection of things that have fallen or been left behind: dried agapanthus pods, the exoskeletons of cicadas (tiny ghosts still clinging to the trees),” Powles writes.

Where is the place your body is anchored? Which body of water is yours?

'Where the Kōwhai Blooms' describes her relationship with the kōwhai, a tree with yellow blooms that is native to New Zealand.

“The exact colour of the bell-shaped petals, dark yellow like melted butter, is for me so deeply entwined with memories of my parents’ house by the sea and the sunlit garden behind it that I did not imagine a kōwhai could grow elsewhere, let alone here,” she writes, with the "here" in question being London.

Much to her surprise, Powles catches sight of the tree in a garden in London. Archival research reveals to her that the kōwhai was brought from New Zealand to England by the botanist Sir Joseph Banks, who accompanied Captain Cook on his first voyage. After a violent landing - during which nine Māori people were killed - seeds were collected and later planted in London’s Chelsea Physic Garden. Before long they became a relatively familiar sight in the gardens of wealthy homeowners.

Powles creates her own map of London, based on the kōwhai trees she sees blooming in the city. In the final paragraph of the essay, she plants a small kōwhai sapling in a pot on her balcony, watching it grow with a mixture of anxiety and care.

“The tree is where I begin and end,” she writes. It symbolises both arrival, departure, and the search for home.

'In the Archive of Waterfalls' is a meditation on Mount Kinabalu, the highest mountain in Borneo and Malaysia - Powles’ grandparents lived nearby. Her grandfather, Chin Phui Kong, was an ichthyologist (a marine biologist specialising in fish), author, and World War Two veteran. As a child, Powles didn’t speak to her grandparents much - partly because of the generational difference, and partly because the language of the household was Hakka, which she doesn’t speak. It’s only in adulthood that she begins to research her grandfather’s work and legacy.

The essay is subtitled with descriptions of colours - ‘cloud-forest white’, ‘National Geographic yellow’ ‘mountain rhododendron red’. Each fragment depicts a memory - of walking through the mountain’s cloud forest, or thumbing through the glossy pages of her grandfather’s magazine.

Halfway through the piece, Powles mentions Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours, a book published in 1814 by a geologist attempting to classify crystals according to colour. As Powles points out, this form of archiving is a colonial practice, trying to standardise knowledge (while disregarding indigenous practices and subjectivities).

“But there is no standard catalogue of colour names. Our language for colours shifts according to our own experiences and memories: the blue of a giant Borneo butterfly’s wings pinned in a glass case; the yellow at the centre of a custard tart. These colours are changing all the time," she writes.

'In the Archive of Waterfalls', Powles has created her own, intensely subjective (and therefore anti-colonial) archive. It doesn’t attempt to classify and categorise - rather, it reveals to her how much more there always is to know.

I think of the last bodies of water I have touched sustaining me, connecting me to places I can’t reach

In the final chapter of the essay - and also the book - Powles answers the questions about what, and where, home is to her. She draws upon a quotation from Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass: “A place becomes a home when it sustains you, when it feeds you in body and in spirit.”

Powles writes: “I think of the last bodies of water I have touched sustaining me, connecting me to places I can’t reach.”

She lists the places where she recently swam in England: Kent, a river in Oxford, Hampstead Heath ladies’ pond. And she writes about her small balcony garden, where she grows small pots of chives, ginger and garlic for cooking, alongside the small kōwhai tree.

This is nature writing at its best - where the ordinary is made miraculous, revelatory. Small Bodies of Water is not a book of certainties, or classifications, and it is not rooted in the traditions of the British pastoral. It is a book about searching, about being ‘tuawai’, a Māori word for non-indigenous (both coloniser and migrant).

“But being tauiwi doesn’t mean I’m left drifting, rootless, untethered to an ancestral homeland. It means tracing the threads back to the roots of my history, my colonial history, and holding all the pieces in my hands. It means always looking for the sea,” Powles writes.

Inspired? Check out our range of wild swimming holidays, from swimming Crete's hidden coves to Hike, Kayak and Wild Swim South Africa!

This article contains affiliate links. Which basically means we make a little commission if you click through and buy something. It doesn’t cost you anything, and it just means we can do more good things in good places.