“Trespassing is about living as though you’re free already,” says Nick Hayes, the author of the Book of Trespass, and The Trespasser’s Companion, a new guide. “Go and swim in a river, peacefully, and with respect and great care for the ecology, and educate yourself about the community through doing so. To do that should not be a crime, and so doing it as if it were not a crime, with an open heart, and not just to make a political action - is one of the most political things you could do.”

The everyday person only has access to 8% of the land in England, Hayes tells me. The illustrator and co-founder of the Right to Roam campaign explained how that situation came to be in his bestselling 2020 release The Book of Trespass, which, in the words of Robert Macfarlane, told "through story, exploration, evocation - the history of trespass (and therefore of freedom)” in England.

We’re excluded from 92% of our land and 97% of our rivers in England, and we’re born into accepting that.

“The Book of Trespass was aimed at exposing something that we take for granted in England as abnormal,” Nick tells me, from his wobbly houseboat on the Thames. “It was to set the context. We’re excluded from 92% of our land and 97% of our rivers in England, and we’re born into accepting that. There are so many more reasonable and responsible examples of how the public could access nature, from Norway to Scotland to Estonia, that benefit not just public mental and physical health, but that are demonstrably proven to benefit nature as well.”

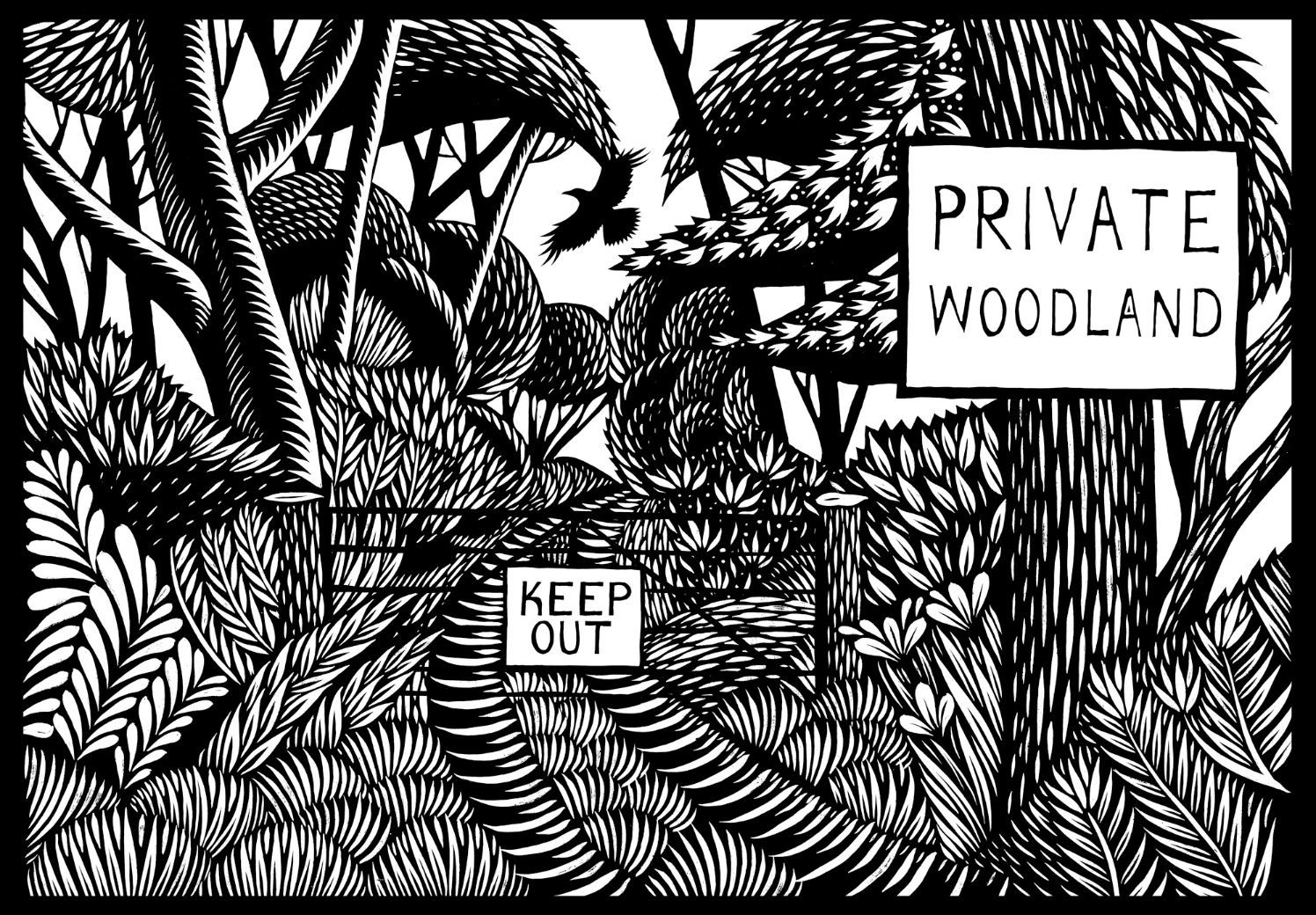

The Trespasser’s Companion is an active “field guide to reclaiming what is already ours” - through trespassing. The book “will start to howl if you leave it indoors for too long.” It “wants mud on its spine” and “feathers between its pages." George Monbiot has described Hayes' work as “remarkable and truly radical.” It is aimed at getting you to go trespassing as part of a bigger movement, and includes testimonials from sheep farmers, artists, land workers and more.

Nick describes trespassing as “a uniquely successful form of protest”. The release of the book coincides with the 90th anniversary of the Mass Trespass of Kinder Scout, which Hayes notes “won us the national parks - and the Forbidden Britain trespasses won us the Countryside and Rights of Way Act”. He goes on: “If we all stood up together, we could gain access to rivers and to land for more than just recreation. We’re trying to reframe the debate from one of nature as recreation to a distinct public health need. The Kinder Trespass was a radical act in the 1930s, but now it's become swallowed up by the establishment. The danger is that we're going to forget what still needs to be done.”

Hayes is often asked if he's encouraging anti-social behaviour.

Don’t just leave no trace. Leave a positive trace.

“We’re encouraging social behaviour,” he says. “People are doing these things anyway. People are going wild camping and dropping litter. We're encouraging a more engaged relationship with the countryside, so they care about it more, so that people don't just treat it, like we saw in lockdown, as another neoliberal buy - turn up, get something, and leave all your crap there because some poor bugger’s on a wage to clear it up. That's not how the countryside works. We're encouraging people not just to not drop litter but to bring an empty bag and pick up any litter that you find. Don’t just leave no trace. Leave a positive trace.”

He gets frustrated with assumptions that the public can’t be trusted.

“It’s part of the propaganda from the land lobby,” he says. “The government only spend £2,000 a year on the countryside on advertising the countryside code. And yet we get blamed for not knowing how to access nature, despite having not grown up with an experience of it. Lighting a fire has its risks, for example, but risk does not necessarily mean that you're a lunatic to engage with it. It's not hard to light a safe fire. It's kind of like we've accepted the infantilisation of the British public."

Hayes recommends people follow the Scottish outdoor access code, which "covers activities that the English Countryside Code still pretends don't occur", such as how to be responsible wild camping, wild swimming or lighting a fire.

There are arguments from campaigners that pressure on the national parks, like Snowdonia and the Lake District, would be eased if public access rights were extended to more places. But access rights in England remain far from complete. While Scotland’s 2003 Land Reform Act granted the country the right to responsible access, the likes of wild camping remain illegal in England.

When we lost our right to access nature, we lost our right to protect it too.

Hayes ultimately puts our acceptance of current land rights down to shifting baseline syndrome. “It goes back to 1067, after William the Conquerer had invaded England,” he says. “All of a sudden there were these great areas of common land that people had right to that were now declared outside of common law. If people lived on them, you would be chucked out of your home.

“Then through the Tudor period and Georgian era there’s this notion of exclusive ownership. Now we’re born into this sense that it’s okay for the Duke of Buccleuch to own 200,000 acres - and for none of the population from Northampton up to Scotland being able to access the rivers or green belt or woodlands that he owns.”

This also means, Hayes notes, that people cannot protect that nature.

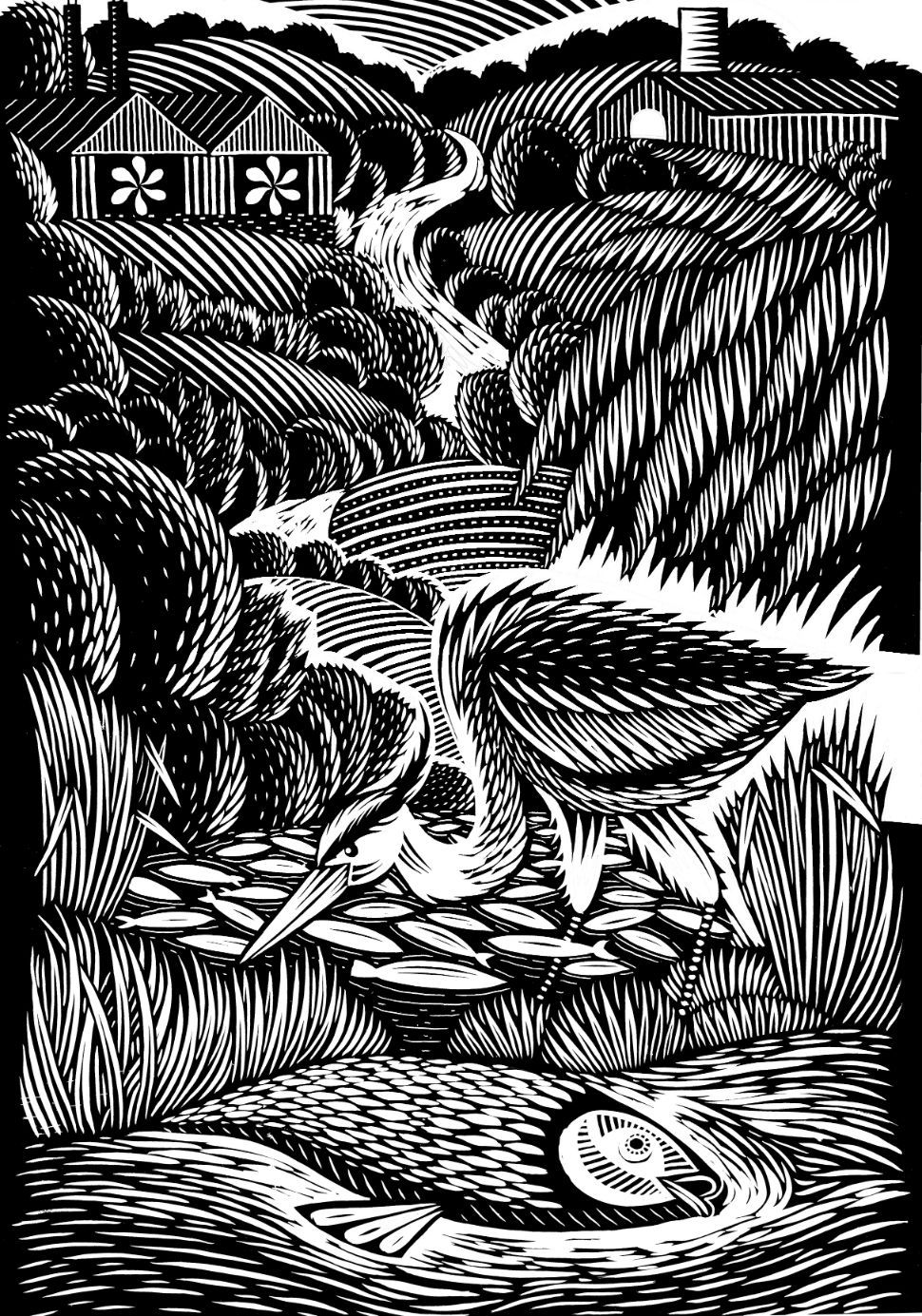

“The Duke is about to cut down 10 acres of woodland in Weekley Hall Woods, even though locals have shown 7,000 people a week use it, to jog in or to boost their mental health or immune system,” he says. “When we lost our right to access nature, we lost our right to protect it too."

He emphasises the importance of connection for the protection of nature.

“I could tell you that the nightingale has declined 90% in England in the last 50 years, but that's just a stat," he says. "If the nightingale you listened to every spring is no longer there, then you feel the loss. It becomes less abstract. You need that visceral, personal relationship. The science proves that - people with greater access to nature behave in more environmentally friendly ways. And when you camp or swim or climb, when you put yourself in a situation where responsibility is required, it teaches responsibility and community, and that goes on to help nature. As a nation, you become less willing to allow it to be exploited.

“The reason nature is in such a devastating situation is precisely because of the industrialisation of the countryside, and the very same system that excludes us.”

What we've got today is nature that has been relegated to this very privileged concept of recreation.

This exclusion happens on varying scales, says Hayes: “It’s always been a class issue. It was the aristocracy who had the yeomanry armies that were able to reinforce their seizure of common land, and then from that they were able to ratify their wealth and expand it. Fast forward and what we've got today is nature that has been relegated to this very privileged concept of recreation, and the leisure industry. It's been okayed that we're only allowed access to 8% of England. Because basically middle-class people can afford the petrol, the car and the overnight stays. It's deemed acceptable that nature is something that you can only access if you can afford it or live near it, but people that can't afford to run a car can’t get access to the countryside - nevermind access in the countryside.

"Only 1% of visitors to national parks last year were from black or people of colour communities. I see the Right to Roam as the spear point that can push through into further conversations.”

And if it's illegal, what is the punishment for trespassing? “Legally, nothing,” Hayes says. “If the gamekeeper asks you to leave and you leave - nothing. If the gamekeeper asks you to leave and you stay and the police come, and they ask you to leave and you stay, then you can be arrested for a breach of the peace."

For many, these repercussions will be worth the act. As Hayes writes in an open letter to landowners, in The Trespasser’s Companion: “For our environment to survive, for our society to thrive, our countryside cannot simply be the preserve of those fortunate enough to own it [...] We want to be a part of the countryside, and we urgently need to reconnect to nature. And until we can have a conversation about how best to make this happen, we will keep coming back.”

Inspired? Check out the Trespasser's Companion wesbite, which includes a Code of Conduct for trespassing, or the Scottish Outdoor Access Code.