Scotty Cornish lives in the French Alps and spends his spare time cycling, trail running and ski touring. He recently completed the 621-mile (1,000km) Alps Divide, a challenging bikepacking race.

“I was quite a reclusive kid, just making models and painting them, until I got into biking,” he says. “After my A levels I took myself off across France for a couple of weeks, with a line drawn on a paper map that took me deep into the Alps. It was double sided; enjoying the adventure but also needing to get away from normal life and live very simply for a week or two.”

Scotty didn’t know it then, but his struggles with ‘normal life’ were due to living with undiagnosed neurodivergence, and going off on his bike gave him much-needed headspace during this period. Scotty's neurodiversity manifests in the form of organisational dyslexia and ADD.

Every experience of neurodiversity (as the word itself indicates) is unique, although there are shared experiences and similarities.

What is Neurodiversity and How Does it Feel?

The definition of neurodivergence is when someone's brain functions differently to what is considered ‘neurotypical’. Neurodiverse conditions include autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and dyslexia, alongside many others. While many of these are considered to be ‘learning difficulties’ or ‘disabilities’, Trixie Harrison – a neurodivergent PhD researcher at the Open University, looking at nature and neurodivergent experience – emphasises that neurodiversity is also a positive celebration of individual difference.

“Neurodiversity, to me, is the idea that differences like autism, ADHD, and dyslexia are natural variations in the way our brains work, not flaws or deficits to be ‘fixed’,” she says. “It’s a perspective that recognises the unique strengths and perspectives each of us brings – whether we think, communicate, or process information differently.”

However, it’s undeniable that some neurodiverse individuals encounter difficulties when they try to shape themselves to fit into a neurotypical society. Scotty, for example, struggled in school with undiagnosed dyslexia.

“Education is very prescribed; a bit of a production line,” he says. “If you can't learn in the way education is delivered, then you're not ‘normal’; you're considered not very capable. Because of my dyslexia there's lots of things going on in my head, and it's hard to pick out what I want to say. I was afraid to be sociable, beyond being with one or two people.”

Both Trixie and Scotty learned they were neurodivergent relatively late in life – Trixie at 44, while struggling with her Masters and then her PhD, and Scotty at 34, while doing a physiotherapy degree.

A tutor suggested that Scotty get a dyslexia test. But after his diagnosis he received little support or guidance, beyond a few tools (such as a voice recorder) and a label he could use to apply for funding. It was when he did his own research and discovered the concept of neurodiversity that things made sense.

“It explained why I didn't fit nicely into a box,” he says. “I used to go to the GP quite regularly because I had problems with sleeping and depression. Now I understand this wasn't clinical depression; I was low because I didn't feel as capable in normal walks of life as my peers. I also have anxious ADD, and feeling like I couldn’t control things was feeding into my depression. Now I understand I'm just a different neurotype, it’s been incredibly liberating. I’m able to talk about it with people without feeling stigmatised.”

Now I understand all this, it’s opened up this whole new world and I’m able to talk about it with people

Due to its very nature, it can be difficult to describe a ‘typical’ neurodivergent experience. However, many neurodiverse people share a difficulty with interoceptive awareness. Interoception is your internal sense of your body’s physical states (such as being hungry or needing the toilet) and emotions (such as anxiety, irritability, sadness). Neurodiverse individuals can struggle with interpreting these signals, leading to trouble with self-regulation and physical health.

“A lot of people are unaware of their interoception and they find it difficult to link,” Trixie says. “So it's like, ‘what am I'm feeling? My stomach's making a noise. What's the context of that?’ And if you don't know the context, you can't apply an action to it. But other neurodiverse people might be really sensitive to things: ‘hunger’ might be an overwhelming feeling of sickness, but they're afraid to eat because they don't want to be sick.”

Neurodiversity and Nature

There’s an increasing body of research into the mental and physical benefits of immersing yourself in nature. It has been proven to reduce stress, improve focus and even, through evoking feelings of awe, increase generosity.

Trixie’s research explores neurodivergent experiences of natural settings on interoceptive wellbeing.

“I'm at the beginning of my data analysis. But essentially people experienced a sense of quiet and began feeling a sense of self-regulation in that environment,” Trixie says. “Forest bathing is just about standing still and really looking at the trees – to remember that you're part of something bigger, and connect with it.

“Many of my participants said that other people in their lives noticed positive changes in them after they spent time in nature."

Scotty has experienced plenty of positive benefits from being out in nature. He gains the most from it when he's physically active.

“Adventure cycling has an extended positive effect on my emotional status," he says. “Anxiety and sadness are replaced with contentment when out cycling, especially when in wild places. What can be overriding anxieties of the future or failure disappear. The mind seems to slow down and become clearer of its usual clutter."

The tree was fine with who they were. The tree wasn’t going to harass them.

Scotty finds that there is a big difference between doing sport in a gym to being out on the trails. “Being in the outdoors, you can completely unmask and be yourself, away from societal stigma,” he says. “In nature, there's that open space, synonymous with having a much more open mind. You'll often meet people with similar mindsets – I've met made many friends in this space over the years."

One of Trixie's study participants had a similar experience of freedom when forest bathing.

“They realised that the tree was fine with who they were. The tree wasn’t going to harass them or judge them,” she says. “They could say what they wanted to this tree and the tree would keep it safe.”

Queer outdoor groups we have spoken to also mention this non-judgemental aspect to nature; a space where nobody is considered 'different' and can just be themselves. It's interesting to ponder whether 'normal' or 'neurotypical' people would also glean this benefit. It gives rise to the question: do neurodiverse people and neurotypical people have different experiences of nature?

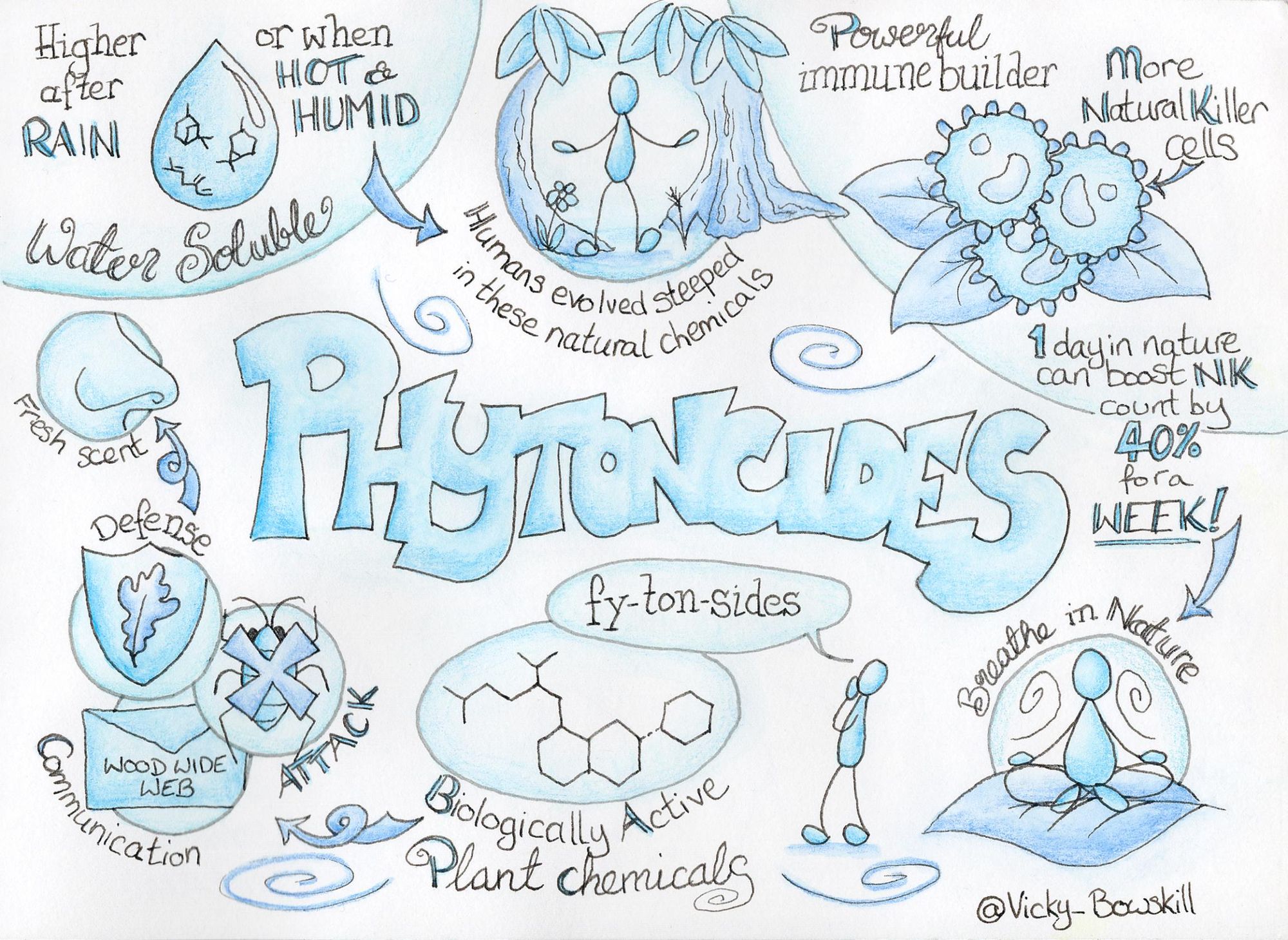

“I don't know how neurotypical people experience nature, so I have no idea,” Trixie says. “However, there’s a host of physiological benefits to being out in nature that everyone experiences. Phytoncides, the plant chemicals you inhale outdoors, boost your killer T cells and help your immunity. Seeing fractals in nature changes your brainwaves and makes you calmer. Both of these things just happen – they impact you whatever your neurotype.

Many neurodivergent people struggle to get out of the house because of paralysis around planning and prioritising

“But my research suggests that the planning around going out in nature is going to be different. Many neurodivergent people struggle to get out of the house because of struggling with anxiety, or paralysis around planning and prioritising. You might not know what shoes to bring, whether you should wear wellingtons, if the weather is going to change. These struggles mean you’re more likely to remain in your house.”

“However, you might then feel an extra benefit of being outdoors, because you have a greater sense of achievement than somebody who just stuck their coat on and wandered out – which I can't imagine being able to do.”

Scotty, who adventures frequently, still experiences this decision paralysis.

“It’s still challenging deciding what to for an event or race even though I’ve done it so many times, especially when keeping weight to a minimum is key,” he says. “I am amazed at what I can do, but get frustrated at myself sometimes when I can’t decide between certain bits of kit!”

Neurodiversity and Outdoor Adventure

Both Trixie and Scotty agree that there are manifold benefits to getting outdoors. The first of these is the simple act of being able to move around.

“The way society is now, there's a tendency towards being more sedentary at home and in the workplace,” Scotty says. “But the hormonal metabolic changes that you get from doing activity have long-term positive effects on your mental health.

"Dopamine, serotonin and endorphins are hormones which increase through activity (as well as reducing cortisol, a stress hormone). This has a positive effect on mood, social behaviour, memory and appetite amongst others, whilst also reducing anxiety.

“Some neurodiverse individuals, especially those with ADHD, have a tendency to get into sport as a way to self-regulate or as an alternative to medication. But it doesn’t work for everyone and a combination of activity and medication may be needed.”

Scotty has also found that adventure sports, particularly bikepacking, have improved his self-esteem.

Being in the middle of nowhere and having to fix stuff has given me problem-solving skills that I’ve transferred to my daily life

“Before my first big trip I had little self-confidence, especially in social situations. Bikepacking changed that,” he says. “I'd meet people in campsites or on en-route, and strike up conversations with them. We shared similar ways of viewing the world. It gave me a connection to people I wouldn’t have otherwise had. I’m still not as social as some people – that’s never going to change – but I’m able to accept and be at ease with that.

“Bikepacking has also given me confidence to deal with difficult situations. Being in the middle of nowhere and having to fix stuff or push through that feeling of ‘I can’t’ has given me problem-solving skills and ways of thinking that I’ve transferred to my daily life. It has also improved my skills in planning, logistics and focus; executive functioning skills which ADHDers commonly have difficulty with. Bikepack racing amplifies all of these, as there is the need for speed, making decisions quickly and effectively.”

The benefits of getting outdoors are undeniable, whoever you are, but neurodiverse people might experience more barriers to getting outside than neurotypical people. A lack of self-confidence is one of them, and as both Trixie and Scott have mentioned, decision paralysis around planning.

“My advice is that you have full permission to prioritise yourself today," Trixie says. “Spending time in nature not only nurtures your well-being but can also create a ripple effect – when you feel better, you’re more likely to inspire and uplift those around you. Take this as your reminder to embrace a moment of care for yourself – you deserve it.”

That’s what I want to tell other neurodiverse people. You fit in places other people don’t, and you might have skills that other people don’t

There are all sorts of ways to enjoy being outdoors, from short walks in your local woods to bikepacking through the Alps. You can enjoy a moment of stillness or a burst of activity – or both. Scotty suggests that people with ADHD (who might struggle to focus) can set goals to become engaged in the outdoors.

“When I first started out, I tended to ride or run at speed and usually set myself goals – how fast could I ride or run up that hill? How fast could I do a certain loop? This helped create the sense of achievement, a form of self validation as I didn’t feel like I was achieving elsewhere,” he says.

Scotty has recently set up Perform Unbound, an online platform promoting the positive intersection between neurodiversity and adventure sport. The goal: to help others reframe what they are capable of. As a health and performance coach, he shares his story to highlight the benefits of staying active, to inspire other neurodiverse individuals and offer education, tips and strategies through his training and support packages for businesses to the educational space.

“That’s what I want to tell other neurodiverse individuals. You’re simply a different neurotype; you see the world in an alternative way and have diverse skills and abilities that are hugely beneficial. We do fit in, but in our own, unique way,” he says.

Feeling inspired? Check out our inclusive adventure holidays around the world.