“Of course, every lady engaged on an Alpine journey will wear a broad-brimmed hat, which will relieve her from the incumbrance of a parasol.” So writes Mrs. Henry Warwick Cole in her pioneering guidebook A Lady’s Tour Round Monte Rosa. Published in 1859, the book was the first such guide ever produced by a woman alpinist in the English language.

The guide documents the adventurer’s experiences on the Tour of Monte Rosa, a now legendary 102-mile hike through the Swiss and Italian Alps, with the Monte Rosa massif - the second highest mountain in western Europe, at its centre.

Warwick Cole's narrative is formed from the details of three separate excursions to the Monte Rosa area, in 1850, 1856 and 1858. It deviates from the usual, modern route in certain places, also documenting “many divergences from the strict route to interesting points in the neighbourhood.”

While large parts of the adventurer's tour were ridden on a horse or mule, the importance of her writing is not only in the documentation of her acts, or the fact that she went at all, but also in her many calls for other Victorian women to follow in her footsteps. This was a woman passionate about adventure, and not content with the societal expectations for women to stay at home.

Two or three hours in the badly-ventilated rooms of a crowded picture gallery will generally produce a feeling of more thorough fatigue than a journey over an eight-hours’ pass in the pure, invigorating mountain air.

She writes that she aims "to give, in the following pages, the benefits of my experience to others, in the hope of inducing them, and especially members of my own sex to follow my example, and visit the valleys which surround this magnificent mountain, some of which have been hitherto but little frequented."

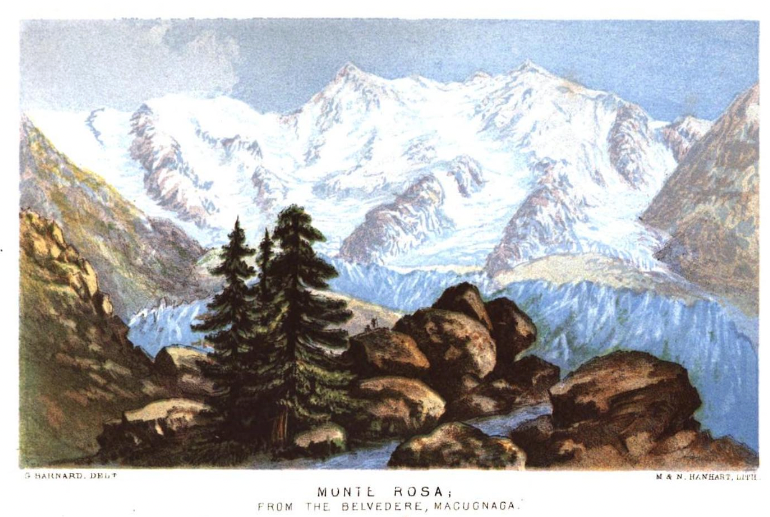

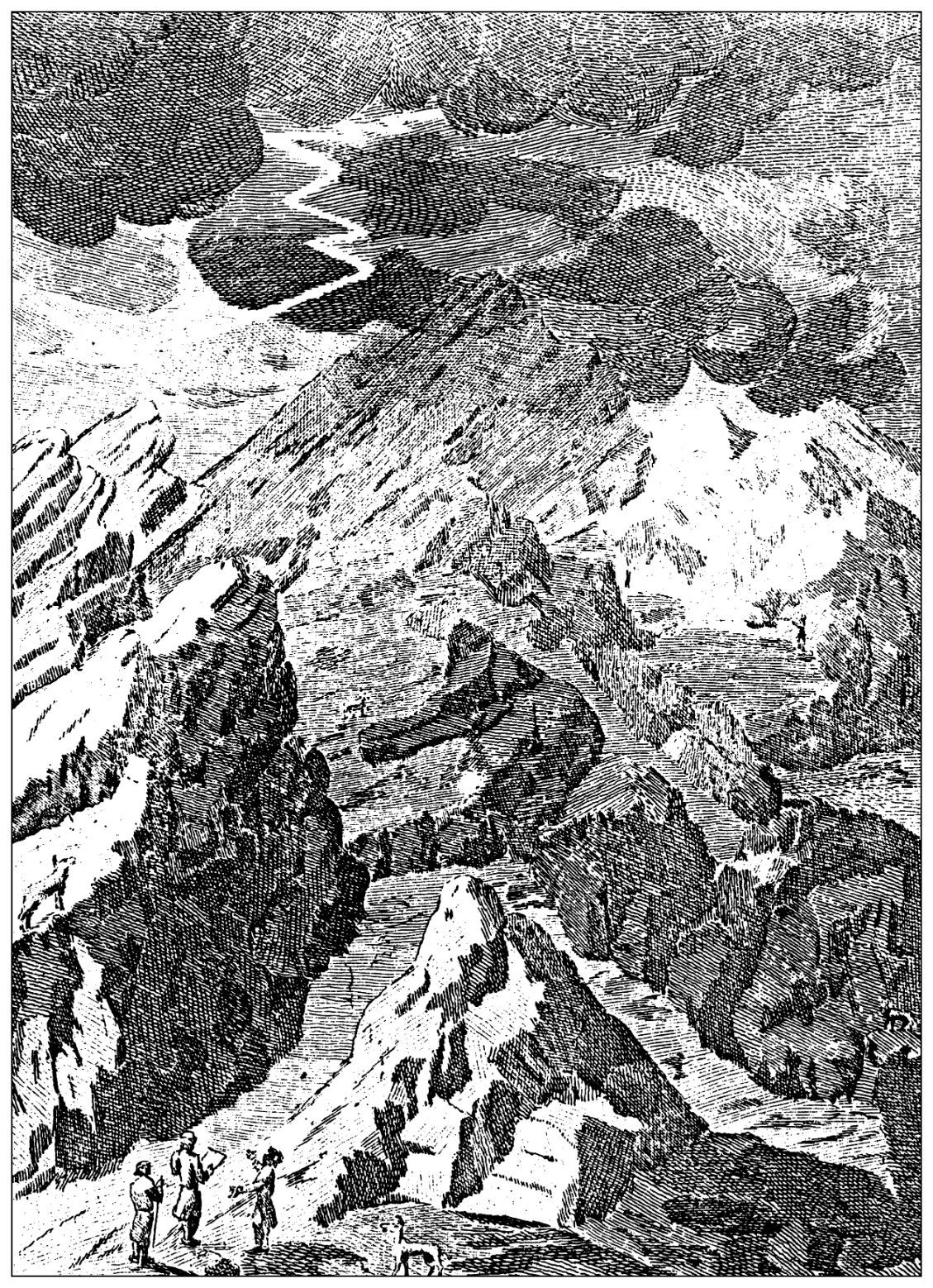

A colour illustration of the Monte Rosa from Mrs. Henry Warwick Cole's book, left, and the introductory page of the book, right. Images: Google Digitization

Throughout her guide, Warwick Cole can also be clearly seen to revel in the still substantial hiking, and strains of adventure, that her party does encounter.

They summit Eggishorn (2,927m), and she writes of how “we were awakened by our alarum at a quarter to 4am, had a hasty breakfast and left the hotel by 5.10am [...] I shall never forget the beauty of that morning, from the moment when the first streak of dawn heralded the approach of the sun till he rose majestically above the horizon. The clear blue sky went through every gradation of colour, each seeming more lovely than the one by which it was preceded.”

I saucily declined the proffered help, as, had I accepted it, I should not have been able to say that I had ascended without assistance...

At 6am, she dismounted her horse, Fritz, and “accompanied the gentleman on foot the rest of the way, which is excessively steep. The path winds upwards amongst large blocks of stone, which form a kind of staircase to the summit. This I reached at 6.55am, without once requiring any assistance. At the top Mr. F—, who was the first to arrive there, offered his hand to assist me up the last few steps over the huge smooth blocks of stone of which the highest peak is composed, but I saucily declined the proffered help, as, had I accepted it, I should not have been able to say that I had ascended without assistance. This I was anxious to do.”

We know startlingly little about Mrs. Henry Warwick Cole, the woman. Even her name is not actually known - her book having being published anonymously, in order, perhaps to avoid a scandal. In the 19th century, and indeed the 20th, mountaineering was not seen as a ladylike, or "motherly" endeavour. Women would be eyed with suspicion for the "undignified" act of hiking alone. There would be social outcry if, worse yet, they walked alone with a male guide.

“They would be questioned by society,” says Paula Williams, of the National Library of Scotland. “It could affect their families or the people around them.” Even other women disapproved, Paula says. They would gossip - “Look what you have to wear? I would never get hot and sweaty. It’s not ladylike.”

What we do know about Mrs. Henry Warwick Cole is what we can deduct from her writing - that she could read several languages, enjoyed the work of Wordsworth, that she was ambitious, determined and had a deep curiosity and interest in the flora, fauna and geological features of the natural world. And, of course, that she didn't care for the Victorian social norms which would have dictated what she should wear, and what she should do while wearing it.

Warwick Cole’s book is full of tips for Victorian ladies hoping to explore the mountains, many of which are based around the fact that, as she outlines, "a lady’s dress is inconvenient for mountain-travelling, even under the most careful management, and therefore every device which may render it less so should be adopted." Here are a few tips, direct from A Lady’s Tour Round Monte Rosa:

- A lady should "have a dress of some light woollen material, such as carmelite or alpaca, which, in case of bad weather, does not look utterly forlorn when it has once been wetted and dried."

- Rings should be sown inside the seams of the dress, and a cord passed through them, the ends of which should be knotted "in such a way that the whole dress may be drawn up at a moment’s notice to the requisite height. If the dress is too long, it catches the stones", especially on downhills.

- You will need "a pair of easily-fitting, strong, treble-soled, broad-footed boots." If the soles are thick enough to screw Lund’s glacier nails - "to be had at Lund’s cutlery shop in Fleet Street" - into them when necessary, "great additional security will be felt in walking over a glacier."

- The traveller "should also have a small waterproof bag, large enough to contain Murray’s indispensable ‘Handbook’, some good maps, a small opera-glass, a few spare straps, and veils for crossing the snow."

- Hungry? Keep "a flask, with a roll, biscuit, or some trifling thing to eat, and to which one can get access to at the moment it is required."

- Oh, and "it is necessary to restrict the travelling library within reasonable limits," though "it requires considerable courage and firmness to do this."

Warwick Cole also notes that ladies “should take nothing with them which can possibly be dispensed with,” so as to not cause the porters to lag behind. “This is especially the case on the Italian side,” she writes, “where two men will grumble at the weight which one sturdy Swiss porter would carry willingly.”

Her writing is full of such humorous quips, balanced by visual scene-setting.

Monte Rosa is “remarkable for the number of its lofty peaks,” she writes, “which are clustered together in a nucleus, which forms the summit, where huge chains of mountains meet and cross each other, and thence, as from a common centre, numerous valleys of exquisite beauty diverge on every side.”

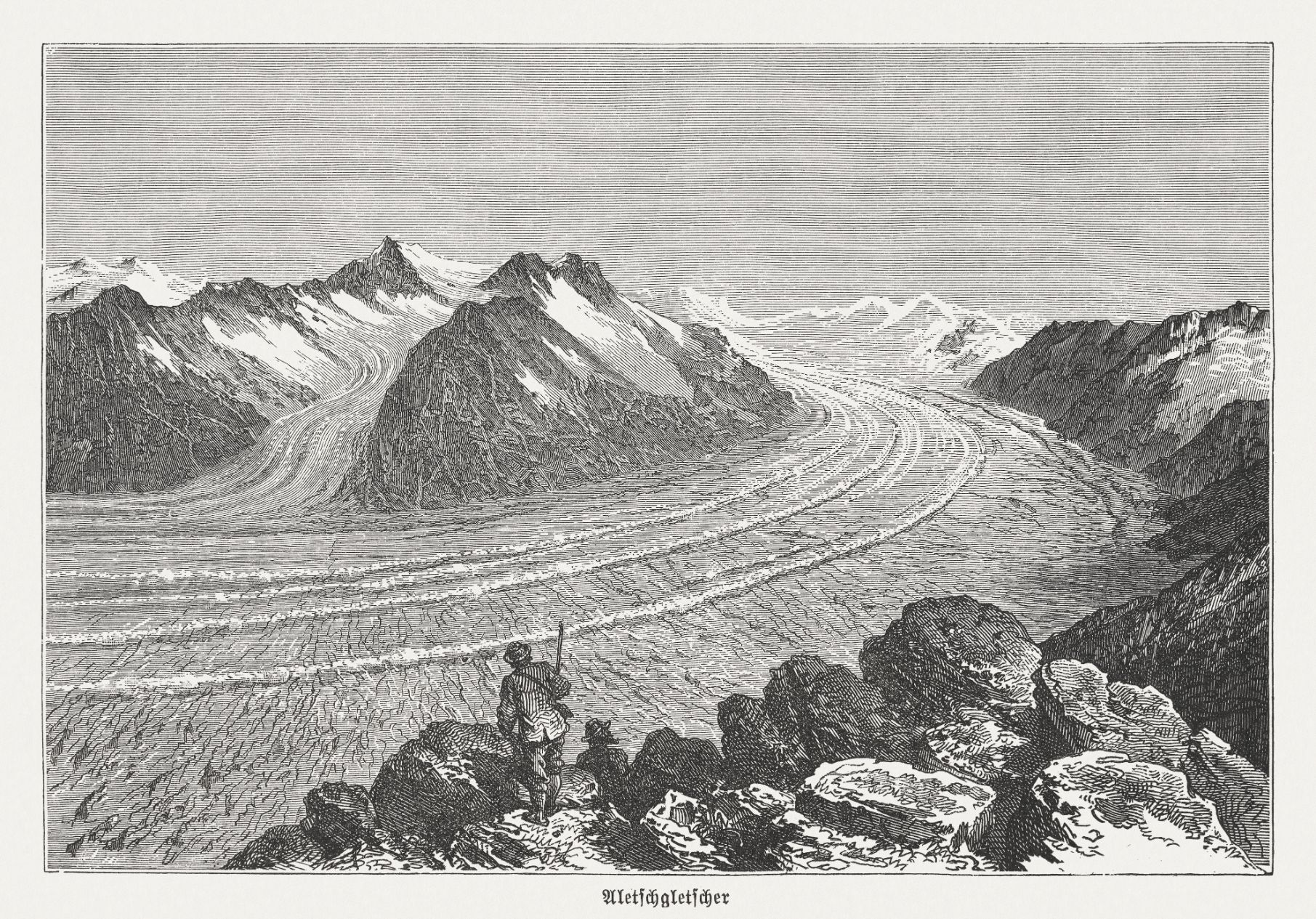

Beyond the Aletsch-horn we saw, with remarkable clearness, the Bernese Alps, including the Jungfrau, without a cloud, the Mönch, and the Eiger.

She writes of the “little Alpine plants and flowers” and tells of the “majestic, snow-capped mountains [...] set in a frame of the richest vegetation.”

Warwick Cole is taken by the Matterhorn, which she refers to by the Italian ‘Mont Cervin’. In Zermatt, she writes of how “the last rays of sun” can be seen “crimsoning the north-western side of the crest of Mont Cervin, whilst the moon is pouring her soft and silvery beams on the eastern face of the mountain.”

She was “much struck with the enormous length of the Aletsch Glacier”, the longest glacier in the Alps, and of the view to Switzerland’s famous mountains “beyond the Aletsch-horn we saw, with remarkable clearness, the Bernese Alps, including the Jungfrau, without a cloud, the Mönch, and the Eiger.”

She makes an attempt on the 3,969m La Grivola, albeit foiled by the elements, and quotes another, unnamed woman mountaineer, who wrote of the beauty of the Theodul Pass - “combining the near grandeur of such vast snowfields, the glittering beauty of the Breithorn, with tis adjacent peaks, and the glories of Monte Rosa, with the stern and overpowering majesty of the Cervin.”

The author mentions other women travelling in the area - “We heard that some English ladies had recently ventured to ride down the whole way to Leukerbad, notwithstanding the terrible danger” - but she was the first to write about it.

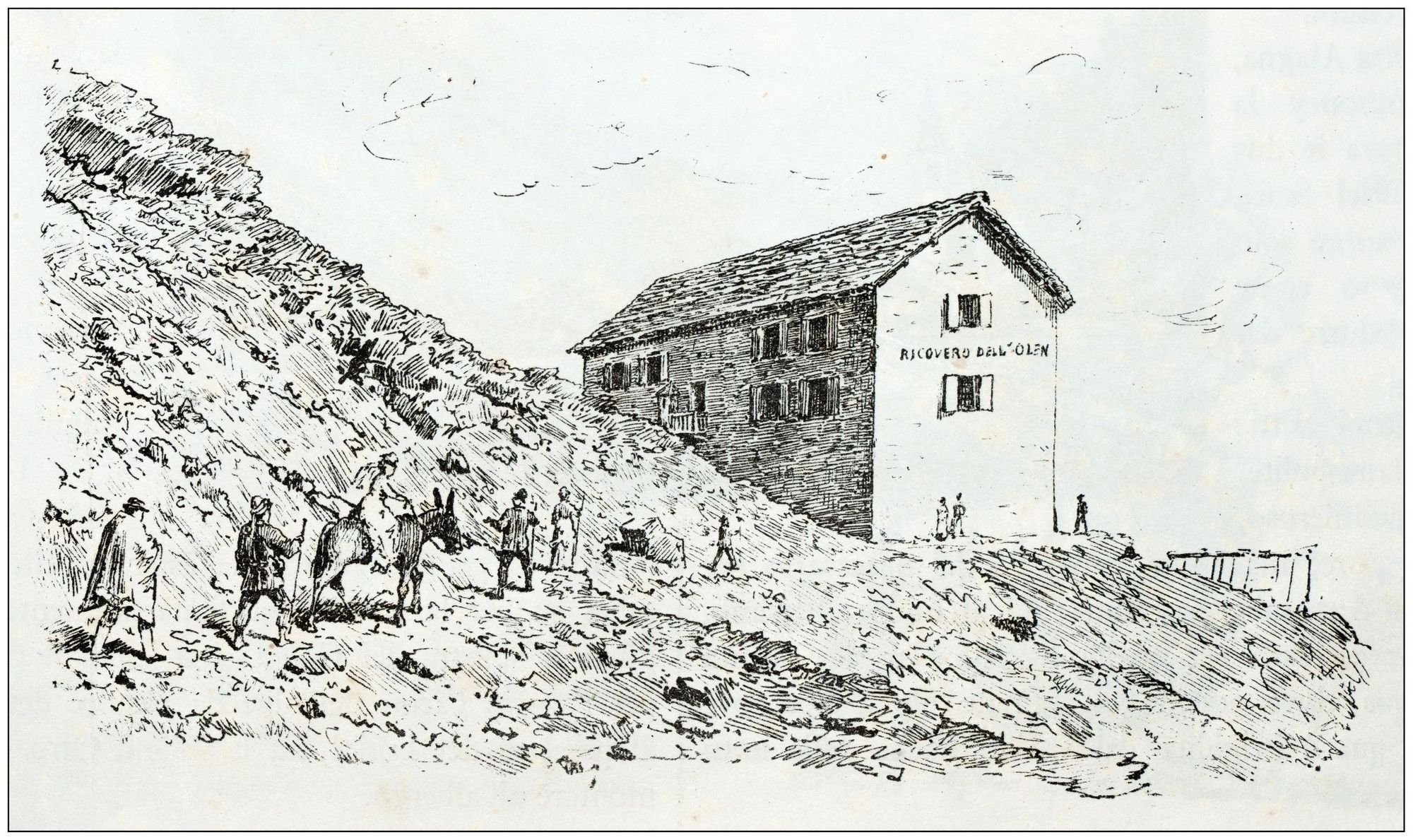

The author also had foresight. “When the variety and beauty of this district, and particularly of the Italian valleys, are more fully known, the tide of visitors will no doubt set in strongly there, and fill the little inns to overflowing,” she wrote, predicting a rise in tourism and refuges. “Better accommodation will then spring up in spots to which none but the most adventurous penetrate at present, merely because there is often no clean and comfortable resting-place to be found.”

But don’t let the rise of crowds put you off. The Monte Rosa is just as stunning today - if a little better known - than it was back when Mrs. Henry Warwick Cole visited in the 1850s. We'll leave the final words of encouragement to the author.

I feel certain that any lady, blessed with moderate health and activity, and has a taste for the picturesque and sublime, may accomplish the Tour of Monte Rosa with great delight.

“Before taking my leave, let me assure you that it requires neither very great strength nor a very dauntless spirit to make the Tour I have described,” the alpinist wrote in her conclusion, with a humility which evaded most male mountaineers of the time. “I feel certain that any lady, blessed with moderate health and activity, who is capable of taking a little exercise 'al fresco', and has a taste for the picturesque and sublime, may accomplish the Tour of Monte Rosa with great delight and few inconveniences, and all who do so must bring back with them a store of delightful recollections for the solace of future years.

“Two or three hours in the badly-ventilated rooms of a crowded picture gallery will generally produce a feeling of more thorough fatigue than a journey over an eight-hours’ pass in the pure, invigorating mountain air.”

Inspired? Trek the Tour del Monte Rosa, and see the stunning massif for yourself!