In 2019, Patrick Mertes and Michael Shelver completed Project 50 in 50 - they climbed to the highest points of all 50 states of the USA in 50 days. The clock started when they reached the top of Denali, a 6,190 metre high (20,310 ft) mountain in Alaska, which had taken nine days to ascend.

“Usually you do an adventure and then you go home and you have dinner. But in this situation, we climbed a huge mountain and had 49 to go,” Michael says. “And you have the monumental task of driving 15,000 miles on top. All of that added together was exceptionally challenging from a physical standpoint, but was also mentally exhausting.”

What makes the feat even more remarkable is that both Patrick and Michael have type one diabetes (T1D). In fact, part of the reason they undertook such a gruelling adventure was to show themselves - and everyone else - that being diabetic doesn’t have to hold you back.

This is a message that Welsh mountaineer Pete Harris, who also has T1D, can get on board with - his Instagram feed is full of the mountains and ridges he climbs. We spoke to Patrick, Michael and Pete about how you can manage diabetes while adventuring, and why you shouldn’t let it stop you from doing the things that you love.

Type One and Type Two Diabetes Explained

Whenever you eat or drink carbohydrates, the body breaks it down into glucose, which is released into your bloodstream. To make sure that the glucose enters our cells and fuels our bodies, you also need insulin, a hormone produced by the pancreas. But with diabetics, to put it simply, this process doesn’t work as it should. Type one diabetics can’t make any insulin at all, whereas type two diabetics produce less insulin, and the body also becomes resistant to it.

“Type one diabetes is an autoimmune disease; your body basically attacks its own pancreas,” Pete explains. “When you normal people - I call you muggles, since I’m a Harry Potter fan - eat something, your brain knows exactly how many carbs it’s had, and what you're going to be doing during the day. Then it releases enough insulin to turn the carbohydrates into glucose for your muscles and your energy - that’s how amazing the human body is.

“Diabetics have to look at a plate of food, calculate the carbs, take into consideration what we're doing in the day, whether we're going to be active or not, and then calculate how many units of insulin we're going to need - every time we eat. You have to be a mathematician, a dietician. So you’ve got your own life in your hands, because if you dose too much, you can have a really serious low.”

A ‘low’ (hypoglycaemia) occurs when your blood sugar drops below what your body needs - if you haven’t eaten enough food or you’ve taken too much insulin. Early symptoms include lightheadedness, an irregular heartbeat and a lack of energy. If left untreated, these can lead to seizures and unconsciousness. To ensure they don’t get to this stage, diabetics will need to raise their blood sugar by consuming carbohydrates - fruit juice or sweets being common choices in urgent situations.

A ‘high’ (hyperglycaemia) is the opposite - when the blood sugar levels in your body are too high - something which happens more slowly than hypoglycaemia. Symptoms of this include increased thirst and more frequent urination. To get energy, your liver will break down fat, which produces acids called ketones. This leads to DKA (diabetic keto-acidosis), which causes symptoms including muscle aches, fruity-smelling breath, extreme fatigue and vomiting - it’s often these symptoms which are the first sign of diabetes in those that have yet to be diagnosed. Left untreated, DKA will eventually lead to a coma.

On average, I think diabetics make 190 more decisions a day. And that's just in everyday life, that's not going out on an expedition on a mountain

“If you don't look after yourself it can be a cruel condition,” Pete says. “If you run your blood sugar high for a long period of time, little fatty cells build up in your blood vessels. A lot of the old timers have had their feet or up to the knees amputated. Then there’s the eyes; a lot of diabetics have got cataracts.”

What makes managing diabetes even more complex, Michael adds, is that it’s not just food and insulin that can affect your blood glucose levels.

“There's over 180 things that can change your blood glucose,” he says. “If you're not having adequate sleep, if you're doing physical activity. So, for example, if we get out of the car and we've had two hours of sleep, our blood glucose is probably going to run quite a bit higher because we're stressed. But then we're going to exercise, which is going to drop blood glucose, and then we're going to go to altitude, which might raise or drop blood glucose.”

Weather is another factor into how much insulin to take. Photos: Pete Harris

“Then there’s the weather, because your body consumes calories staying warm, and how you’re feeling,” Pete adds. “I've got to the top of a climb before now and I've taken insulin and my friends have asked, ‘haven't you just taken insulin?’ and I tell them it’s for the expected adrenaline spike in a minute - because adrenaline will make your blood sugar just shoot up.”

“You've got to make so many decisions. On average, I think diabetics make 190 more decisions a day. And that's just in everyday life, that's not going out on an expedition on a mountain.”

Often it's talked about as a lifestyle disease, because this person was lazy or isn't eating right, or isn’t exercising and that's just not the case

Constant decision-making can cause mental fatigue. Added to this is having the stigma that comes with diabetes.

“The unfortunate reality with diabetes, both type 1 and type 2, is often it's talked about as a lifestyle disease, because this person was lazy or isn't eating right, or isn’t exercising, and that's just not the case,” Michael says. “Type 1 is an autoimmune disease, and with Type 2 diabetes there are a huge amount of genetic factors that play a part.”

But neither Patrick, Michael nor Pete want their diabetes to get in the way of their adventures in the outdoors. So how do they manage their condition in remote, unpredictable environments?

Managing Diabetes in the Outdoors

Managing diabetes is trial and error - activity levels and body weight all play a part when it comes to working out how much insulin is needed for the carbohydrates you consume. What’s more, there are two different types of insulin dosing: basal, which keeps your blood sugar steady; and bolus, a fast-acting insulin you take just before eating. There are also different ways of administering insulin - via injections or through an insulin pump. For Project 50 in 50, Michael and Patrick used insulin pumps linked to continuous glucose monitors, which automatically monitor your blood glucose levels every few minutes.

“The insulin pump gives you a steady basal rate of insulin, which is what someone who's not living with diabetes’ pancreas does as an organ,” Patrick explains. “At the time the technology was that if the monitor noticed your blood glucose was going too low, it would actually cut off the insulin to potentially prevent that from happening. You also have to announce when you're eating anything, especially carbohydrates, and then administer insulin through a bolus pump 15 minutes before you actually consume it.

“This technology is basically built for your day-to-day lifestyle, so we really put it to the test by doing a project of this magnitude. All that being said, diabetes management was not beautiful during the project. We certainly had our numerous highs and lows, but we were adamant about staying safe, and also gave ourselves some grace knowing that we weren't going to have perfect management during something this extreme.”

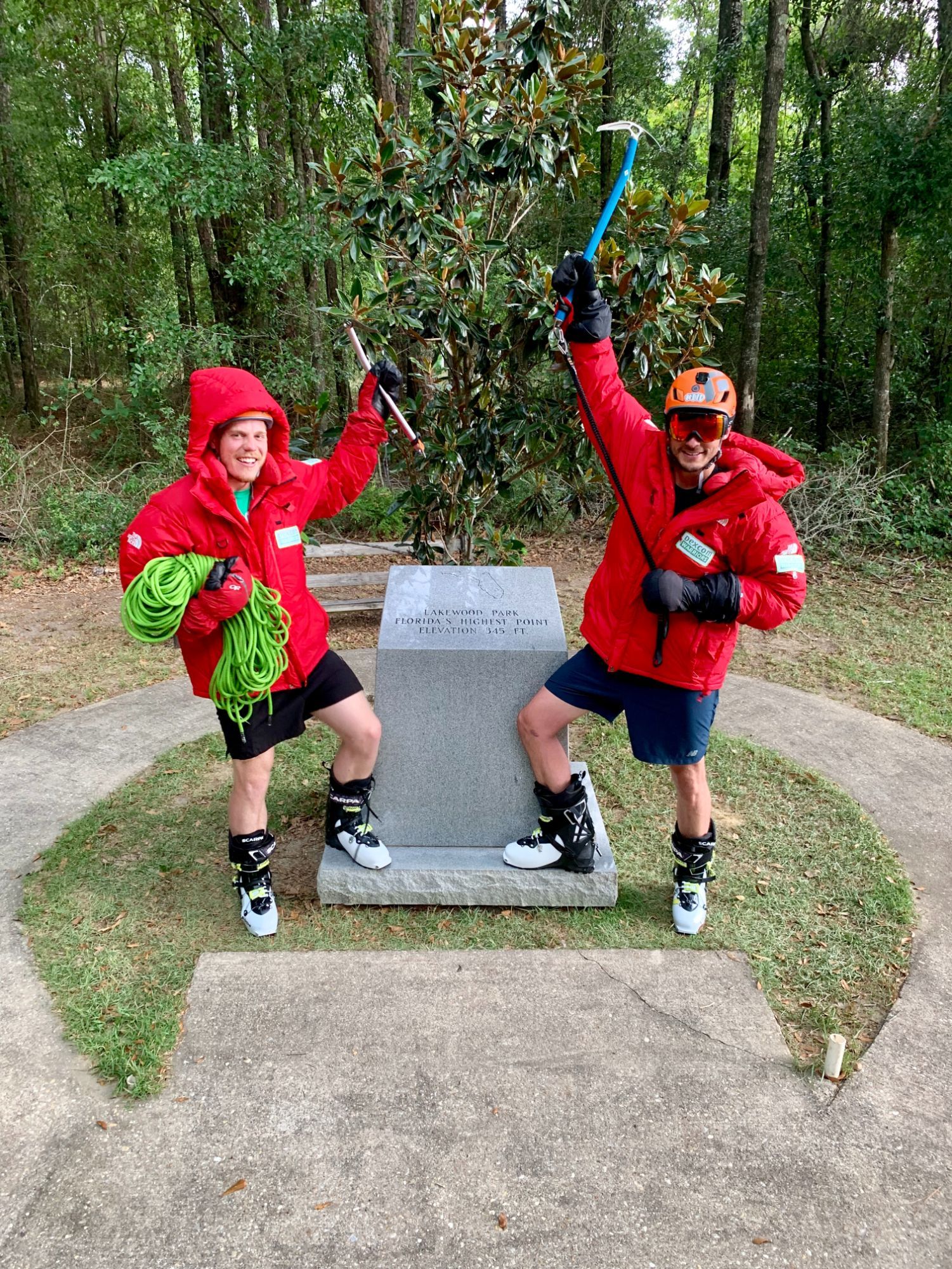

On the highest point in Florida, Britton Hill (105m) and Mount Rainier, Washington (4,392m). Photos: Project 50 in 50.

The medical systems in the US and UK are very different: in the UK you need to meet certain criteria to get an insulin pump on the NHS, and Pete isn’t eligible. He’s particularly attracted to them because of the reduced injection sites, having calculated that he’s given himself around 85,000 injections during his lifetime. He does, however, explain that injecting insulin has become much easier as technology has advanced.

When you're able to frame diabetes as an obstacle that has made you into the person you are today...that can change your whole life

“The innovation that's happened over the past 10 years has made it so much easier,” he says. “I've got a sensor on my arm and you wave your phone over it and it tells you your blood sugar. If you go high or low, it'll send an alarm to your phone. That’s been amazing, especially out on the mountains. To do your blood sugar, you used to have to take a sterile wipe and prick your finger - that was especially hard in the winter.

“When I first started doing my own injections, you used to have to take the insulin out of one vial, get all the air bubbles out; take the insulin out of another vial, get all the air bubbles out, and mix it together. It used to take about 15 minutes, whereas now it's in a pen and it's done in two seconds. I don't want to say it's easy to be a diabetic, but it's a lot easier now than it was 15 years ago.”

Photos from Pete's adventures. Photos: Pete Harris.

Patrick and Michael agree that technological advances in diabetes management have really helped them stay safe in the mountains. But Patrick also believes that reframing his attitude towards diabetes has helped him live a more adventurous lifestyle.

“I don't think Mike and I would be the people that we are today if it weren't for diabetes,” he says. “I geek out about high performers, and a lot of them are built from ‘iron sharpens iron’ - from navigating the obstacles in their lives. There's days when I'm very guilty of not being able to do this, but when you're able to frame diabetes as an obstacle that has made you into the person you are today, being grateful as opposed to thinking of it as this huge weight and burden, that can change your whole life.”

Michael believes that having T1D can even, if viewed in the right light, be considered as something that will help you in your adventures.

“Type 1 diabetes was the perfect training preparation because again this project was 50 days with no days off, limited sleep, and diabetes is like that as well,” he says. “No matter how miserable you feel, or how tired you are, how hungry or cold or hot, you still have to manage it - that builds a lot of fortitude. And I think that that's actually a positive skill set that you can take into the backcountry. If you can handle managing diabetes out in the world, you're gonna be pretty good at backcountry adventures because a lot of the skills carry over.”

However, that doesn’t mean that adventuring with diabetes is always difficult.

“My blood sugars are never better than when I'm out on a mountain,” Pete says. “That’s because I’m happy - if you're stressed or anxious or feeling depressed, that can really affect your blood sugars - being on a mountain makes me feel more myself. I’m not stressed; all I'm thinking about is ‘where am I going to put my hand next?’”

No matter how miserable you feel, or how tired you are, how hungry or cold or hot, you still have to manage it - that builds a lot of fortitude

Michael agrees. “Diabetes is just an accessory that we bring along on our trip; it’s not what we're thinking about the majority of the time. We're thinking about how to get to the summit. How to stay safe. How to enjoy this trip, or how to take fun pictures.”

However, all three men highlight the importance of starting off with smaller adventures and slowly building up your skills before jumping into larger projects.

“Don't go for the big mountains straight away, just do some nice hikes,” Pete says. “There's so many beautiful places in the UK; you don't even need to go abroad to have a proper adventure holiday. Just start easy and work your way up. Start learning what foods do what to you, so you can learn what to pack. Just enjoy it - when you’re stressed, it's releasing hormones into your body which are affecting your blood sugars. And if anyone wants any tips, just send me a message.”

Inspired? If you'd like to try mountaineering in a small group, then check out our Mountain Climbing and Peaks Over 4000m collections.