It can be difficult to find the headspace to think about the fight to save our planet when we’re currently so focused on saving the people who call it home. But while CO2 emissions from aviation reduced by 60% in 2020, and there were widespread reports of nature returning to urban spaces around the world, other, new problems also presented themselves during the pandemic - in particular, an uptake in single-use plastics, from packaging and PPE.

As I looked at my keep-cup gathering dust in my cupboard one day, I wondered - how has Covid impacted the zero waste community? We speak to three voices in the movement to find out.

The reusable cup has become an emblem for the zero waste movement. A UK government report from 2018 estimated 2.5 billion coffee cups are thrown away each year, and that was before 2020, a year which saw reusable cups temporarily banned from most coffee shops for safety reasons. Single-use might feel safer, but in July 2020 over 125 health experts from around the globe signed a statement concluding that reusable containers posed no extra Covid threat.

“There was an assumption that single-use plastic was somehow safer,” says Steve Hynd, who is a Campaign Manager for City to Sea, a Bristol-based not-for-profit at the forefront of the fight against single-use plastics during the pandemic. “We showed people this joint letter from over 100 experts and then we put together useful guidance about how to use reusables safely.”

City to Sea was founded from a love for the oceans and campaigns to stop plastic pollution at the source. Recent campaigns include 'Getting Reusables Back on the Menu', reassuring businesses and consumers that reusables don’t increase the chance of virus transmission, and 'Contactless Coffee', showing in four simple steps how to safely serve coffee in a reusable cup.

We’ve hit peak single-use plastic. It’s just about how quickly we transition away. We’re saying there’s no reason to slow down.

After seeing the evidence, “a few of the big chains started to re-accept reusables” says Steve, including Starbucks, Costa and Pret a Manger. “But some big names still aren’t accepting them for no good reason. This is partly pushed by the plastic industry, who’ve seen this as an opportunity to give themselves a lifeline in a dying industry. We’ve hit peak single-use plastic. It’s just about how quickly we transition away. We’re saying there’s no reason to slow down.”

Disposable masks in gutters and on beaches have also now become a common sight. “There were no established behaviour patterns for how to interact with PPE,” says Steve. “So we tried to get our message out early. Healthcare professionals need different standards, but reusable masks are perfectly adequate for me and you in the majority of situations. That’s supported by the World Health Organization (WHO). Equally, WHO didn’t recommend disposable gloves, but back in April 2020 everybody was wearing them. People were just trying to do whatever was right to keep themselves and others safe.”

We’re soon going to see more plastic masks in the Mediterranean Sea than we are jellyfish. That’s the prediction of Laurent Lombard of Opération Mer Propre, a French environmental group, who released viral underwater footage in 2020 of algae-entangled masks in the sea.

Even before Covid, it’s estimated 13 million tonnes of plastic ended up in the ocean each year.

“It was a risk as an organisation, to start talking about plastic pollution in the middle of a global health pandemic,” says Hynd. “Because rightly, people say ‘shouldn’t the priority be on public health at the moment?’ We would say it doesn’t have to be one or the other.

"What we're looking for is about herd mentality; about people self-reinforcing behaviour. Each one of us is an influencer for those around us; and there’s also opportunity here. Local food hubs have seen a real boom, and suddenly having milkmen deliver in a reusable glass container isn’t just nostalgic, it’s one more reason why you wouldn’t have to go to the shops.”

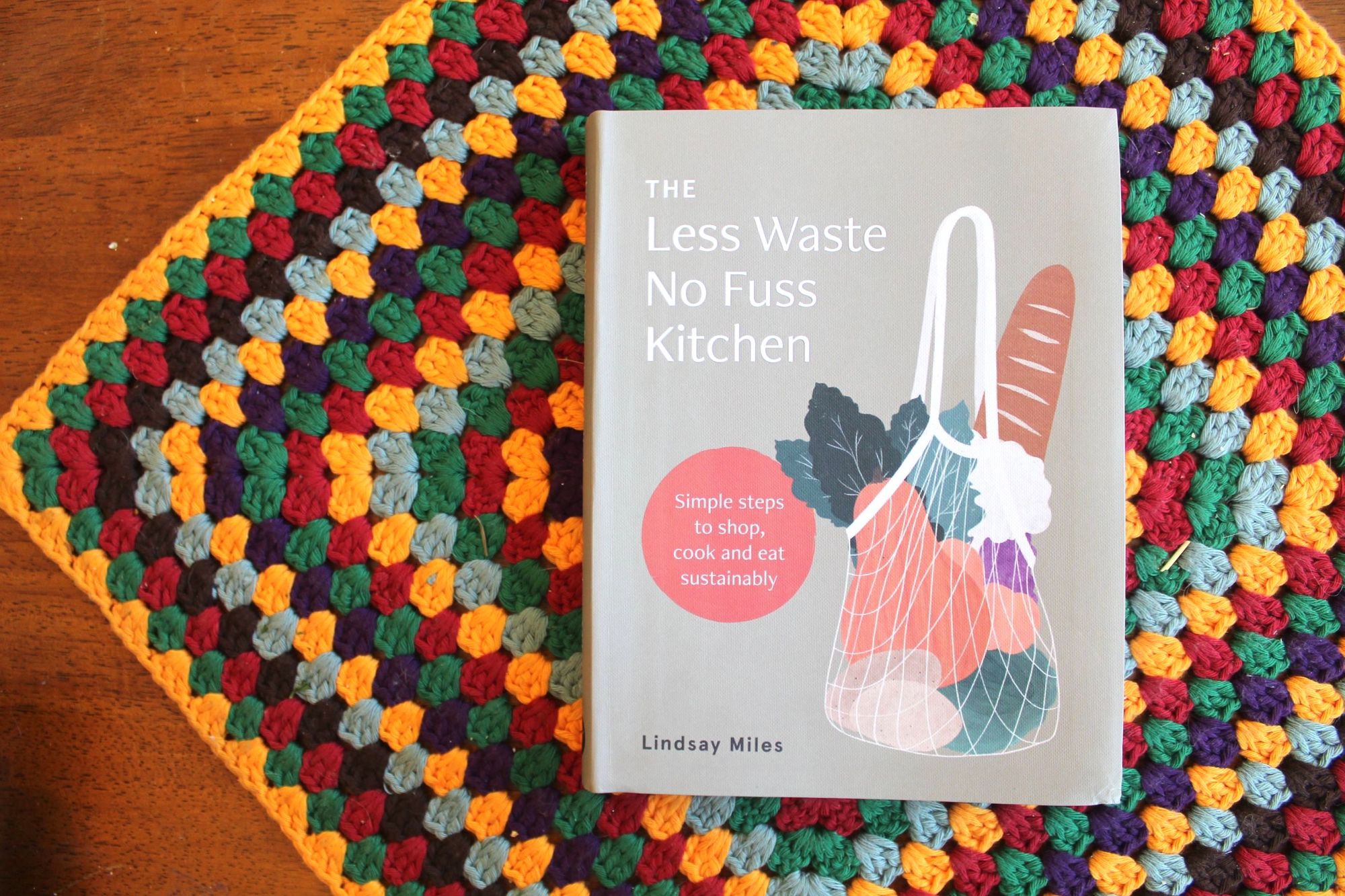

Author Lindsay Miles has been on her zero waste journey for over nine years. Her latest book on the topic, The Less Waste, No Fuss Kitchen came out in summer 2020 and is an accessible guide to cutting down on waste, designed for busy people who want to make simple changes.

“I generally go to multiple places to buy things but obviously during Covid, you don’t want to be going to five different shops,” says Miles, who is based in Perth, Australia. “A lot of things became less accessible, but generally bulk stores [also known as zero waste shops] were open.

Going plastic free sounds difficult, but when you break it down into buying loose carrots, getting olives in a glass jar - it all becomes manageable.

“What I did notice was the mental energy I was spending scrolling the news and worrying about Covid. That takes up a lot of energy, so sometimes you’ve got nothing left to think about zero waste living. I’ve been doing this for nine years, and when you’ve developed the habits it’s easy to stick to them, but if you’re just starting out, I can see how it would be easy for things to slip.”

That said, As Hynd remarked, local food hubs have been booming. Miles suggests one reason for this is that they managed to stay stocked in items supermarkets were running out of. “There were no empty shelves or people punching each other over toilet rolls,” she says. “They had flour and sugar and they always had all the essentials.”

The idea of going zero waste can seem quite stressful, but Miles is keen to emphasise that like all behaviour change - once you’re in the habit, it’s no extra work at all.

“It can be overwhelming at first, but you get used to it,” she says. “Going plastic free sounds difficult, but when you break it down into buying loose carrots, getting olives in a glass jar - it all becomes manageable.”

Miles’ advice is to take the journey one step at a time, and not to beat yourself up if you do slip.

“You make decisions about waste every single day,” she says. “Especially with food. So if you're having a crap day and you want a takeaway and it comes in plastic, then the next day go to the shops and buy some loose vegetables and make something. You can have a bad day or a bad week or month or year, but the next day will come and you make all of these decisions again.

“For me the important thing is just that people do what they can. We need to give people a bit of slack. The current system isn’t set up to do things the way we would have done 100 years ago.”

Zero-waste shops are one place trying to change our shopping habits. Another example are community co-operatives - member-led organisations aiming to counter consumerist culture.

Joanne Elston and Billie Dunleviewood are members of the SHRUB Co-operative in Edinburgh. “SHRUB has a simple, overarching mission which informs everything that we do,” says Billie. “A vision for a world without waste.”

Food waste was an issue before Covid, and will be one after. NGO WRAP found that 9.5 million tonnes of food are wasted every year in the UK alone, 70% of which comes from our homes.

It creates an opportunity for environmental justice that doesn’t only address the environment but also social inequality.

SHRUB Coop operates a ‘food sharing hub’ to try and offset some of that. You might have heard of dumpster diving; searching through supermarket bins to save perfectly edible food. This is similar, but SHRUB works with supermarkets to collect the food, then offers it to the public on a pay what you want basis. It’s Scotland's first “rescued food shop”, and on any given day you can find anything from bread and veg galore to frozen meat and artisan donuts.

“It creates an opportunity for environmental justice that doesn’t only address the environment but also social inequality,” Billie says. “For a food bank, it can take weeks to get a referral. We can just give food away to people - basically for free - and it saves it from going to waste.”

It seems fitting that SHRUB's food hub is on Bread Street. Bread waste in UK homes generates 318,000 tonnes of CO2 annually – the same as 140,000 cars. But while much of the Coop has had to go online during the pandemic - there’s also a swap shop, weekly craft sessions and meditations - the food hub has stayed open throughout. “There’s been so much food coming in,” says Joanne. “A lot goes back out to hostels and to other places - we can’t give it all away.”

Interestingly, food waste fell during lockdown. People were taking fewer supermarket trips and managing food better, according to WRAP. 36% of UK households say they were throwing away less uneaten food, but that stat is slipping as lockdown restrictions in the country are eased.

It’s something we hear all the time, how vital it is to have a community who can confirm your choices

Still, if there were fears the pandemic would see a decline in new interest, it hasn’t materialised. Membership numbers at the Coop have steadily increased throughout 2020.

While resources like the SHRUB are invaluable in offsetting supermarket waste, both Joanne and Billie are keen to emphasise how much the community aspect of the Coop has helped them, and the other members of the Coop, stay on their zero waste mission during Covid.

“If you're in a flat share with people who aren't on that path you can start to feel totally isolated from it all,” says Billie. “It’s something we hear all the time, how vital it is to have a community who can confirm your choices - and offer alternatives to things you haven’t changed just yet.”

It’s clear that the zero waste movement is facing its challenges in Covid, but from each voice I speak to one thing is clear; community is key, and action are prevalent - and necessary - as ever.

Lead illustration by Nik Martin. Find out more about Lindsay Miles, City to Sea and the SHRUB Co-op here.