In 1865, a ship carrying 153 Welsh passengers departed from Liverpool. Its destination: the uncharted wilderness of Patagonia, where they planned to settle. Why Patagonia? Well, one might argue that they had been misled…

The key architect of this plan was Michael D Jones, a Welsh Nonconformist minister. He believed that Welsh culture was being destroyed by English rule and the Anglican church. He was particularly concerned with preserving the Welsh language, which he felt was in danger of disappearing as more Welsh people became English-speaking.

His solution: a mass exodus to a remote corner of the world, where a Welsh colony could live isolated from outside influences. Eventually, he hit upon the idea of Patagonia, and began corresponding with the Argentine government about settling in the remote Bahia Blanca region. The request was granted - it suited the Argentines to have a colony in Bahia Blanca, which was then the subject of a dispute with neighbouring Chile.

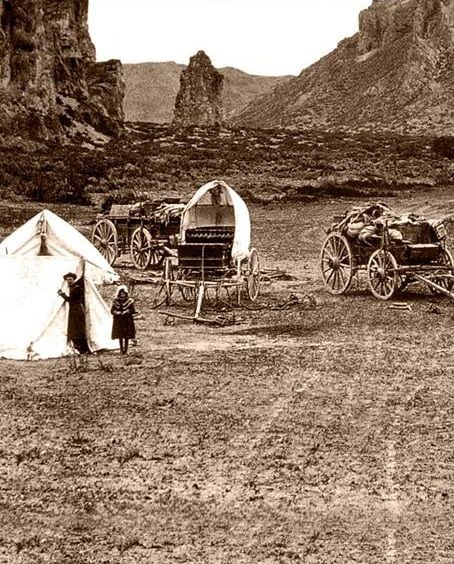

Imagine how they must have felt at the sight of this barren land, their dreams of a fertile paradise turning to dust in their mouths

There was just one problem - previous British surveys had branded Patagonia as a desert which would never support human life. So in 1862, Jones sent fellow idealist Lewis Jones and Captain Love Jones-Parry off to Patagonia to assess its suitability for settlement. Lewis Jones returned with glowing - some might say misleading - reports of the terrain. He’d also extracted a promise of 100 acres of land per family from the government.

Michael Jones poured a significant amount of time, energy and his wife’s fortune into encouraging his countrymen to emigrate to Patagonia. Alongside the 100 acres, each family was promised “at least five horses, 10 cows, 20 sheep, two or three pecks of wheat, a plough peculiar to the country, and a number of fruit trees.”

The campaign worked. On the 28th May 1865, a full 153 would-be colonists boarded the tea-clipper Mimosa. They were going to create their own utopia, which they would call Y Wladfa (‘the colony’).

They were each carrying just a few shillings, and the possessions they’d been instructed to bring: “a bed (for one), blanket, towels, knife and fork, a tea and a tablespoon, a plate or two, a tin to raise water, a cup and a saucer rather large, a boiling pot, a quart tin, and one that will hold three gallons.”

Exactly two months later, on the 28th July 1865, the settlers arrived in Patagonia and docked at New Bay, an uninhabited bay surrounded by an arid, inhospitable plain. Imagine how they must have felt at the sight of this barren land, their dreams of a fertile paradise turning to dust in their mouths.

The settlers founded a settlement in New Bay called Madryn. At first, they camped in wooden shacks on the beach, or sheltered in nearby caves. They planted wheat, which didn’t grow in the dry soil. There was no potable water.

It quickly became apparent that the area was unfit for habitation, so the settlers made the 40-mile trek to the Chubut Valley, which Jones had intended as their final destination. While they had been misled about the fertility of the region, it did at least have fresh water, in the form of a river running through the valley.

Over the next year, the settlers tried to eke out a living. They built small cottages from mud and stone. The sheep they’d brought with them escaped. Their crops did not grow. The cows that they’d been sent were half wild, and attacked anyone who tried to milk them.

Part of the problem was that the settlers were unused to subsistence farming. In the group there were 78 children and 32 women; of the men, only four were farm workers - others included clergymen, a tailor, a printer and coal miners. Even the farm workers were completely unused to the harsh, dry conditions.

With only a few months of supplies left, their clothes and morale in tatters, the colonists sent an appeal for help to the government of the Falkland Islands. HMS Triton arrived in July 1866 - the captain distributed shoes and sold cloth to the settlers, while the ship’s doctor attended patients. Aside from scurvy, they were in good health - he recommended an urgent dispatch of lime juice and soap.

But the wheat crop in 1866 was again a failure. The colonists decided to leave, and returned to Madryn to await a ship from Buenos Aires. It arrived with Welsh delegates onboard, who relayed a message - the Minister of the Interior had promised them a monthly grant of £140 for food and seeds for the next year. This convinced most settlers to stay.

He recommended an urgent dispatch of lime juice and soap

And so they persisted. They learned from the local gauchos how to lasso cows and tether them to a post if they wanted to milk them. Despite living in constant fear of the indigenous Tehuelche people, relations between the two were peaceful. The Tehuelche came to the colony to trade; they taught the settlers how to hunt guanacos (an animal similar to a llama) and wild ostriches.

In 1867, unwilling to plough his field, Aaron Jenkins scattered his wheat seeds on the ground near the river. It rose higher than usual that year, and Jenkins realised by cutting a channel, he could divert water to his parched crops. Much to his surprise, bright green shoots appeared. So he repeated the flooding a few weeks later. The crop flourished and the settlers quickly adopted a communal irrigation system.

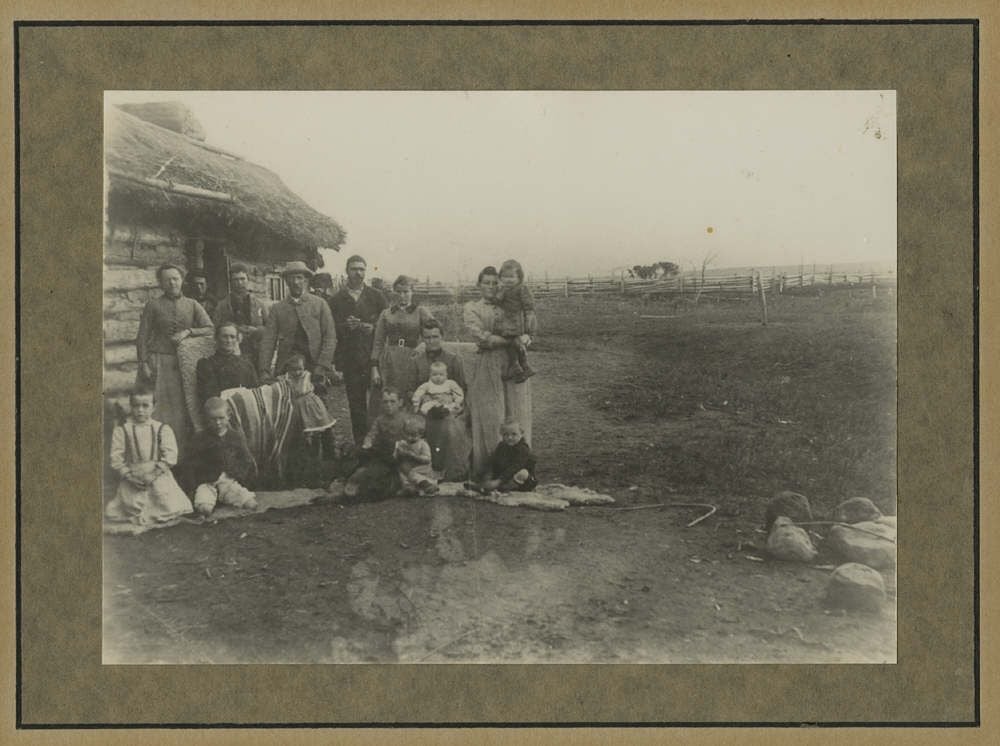

It was a difficult life, but the worst was over. Surplus wheat was produced and exported to Buenos Aires, alongside Chubut butter and cheese. The good news reached Wales, and further emigrants arrived. By 1885 they numbered 1600. Some went further up the valley and established sheep farms; the wool also became a valuable export.

In 1884, Chubut was declared a territory of the Argentine Republic. This meant that Argentine schools were opened by authorities, and the colonists were required to do military drill. However, they did succeed in preserving the customs and language of their forefathers.

Visiting in 1902, Sir Thomas Holdich described his surprise when encountering a series of neat cottages standing in manicured gardens in the Andean foothills.

“We were welcomed in for tea by the housewife and her good-looking daughter…the atmosphere of the place was wholesome, clean and indisputably Welsh,” he wrote.

Fast forward to the present day and Y Wladfa is firmly established. Puerto Madryn - where the settlers initially disembarked - is now a bustling city with around 110,000 inhabitants. The Chubut Valley is still settled - Trelew, with around 100,000 inhabitants, is one of the largest towns in the region.

While only 5,000 of the population are Welsh-speaking, it’s estimated that there are around 50,000 people with Welsh heritage. You’ll still find quaint cottages, chapels and tea houses serving bara brith in the area. Welsh culture persists in Welsh signage, Eisteddfod festivals and Gŵyl y Gland (events commemorating the Welsh landing in Argentina).

Feeling inspired? Check out our Adventures in Patagonia.