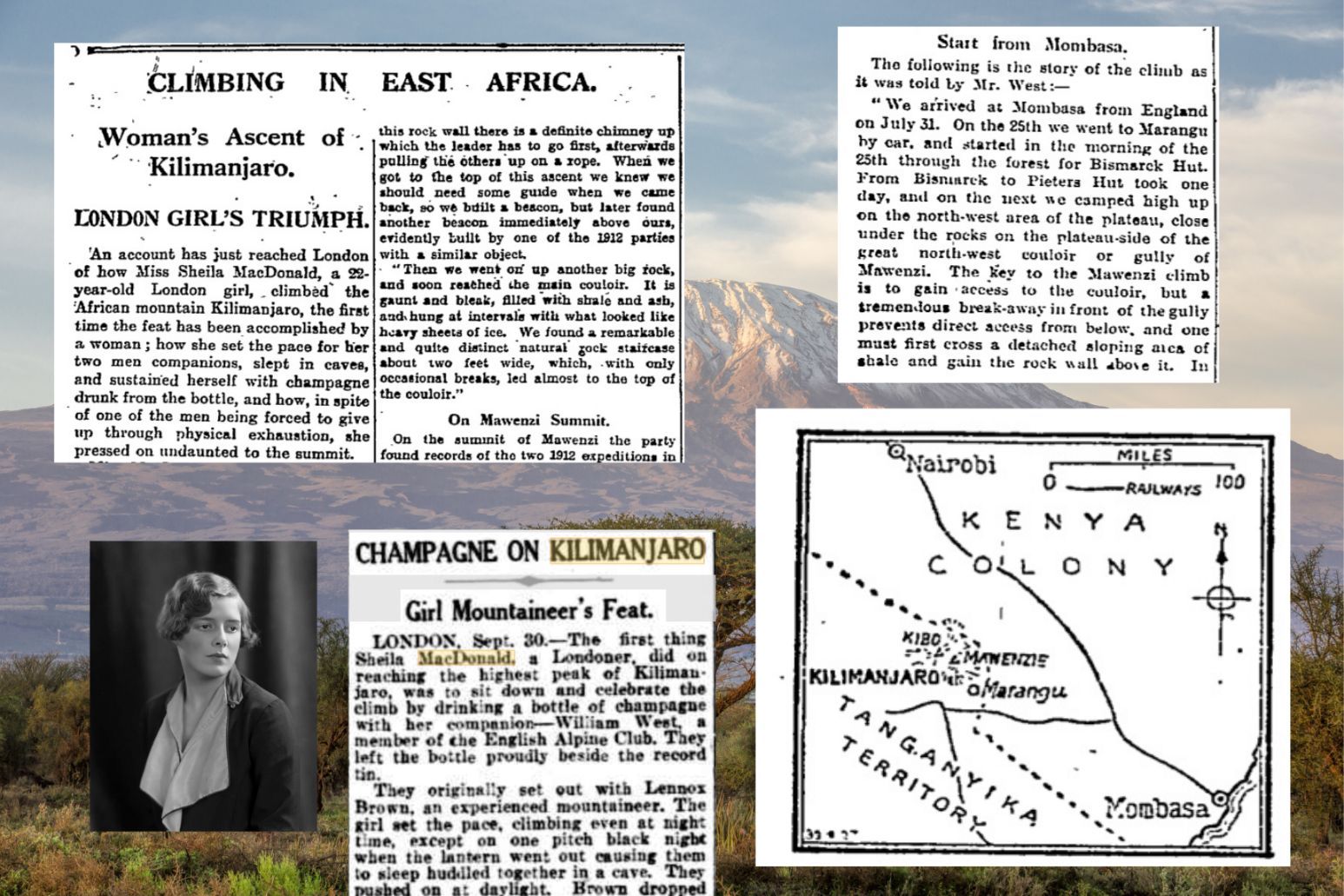

On the 30th of September 1927, The Guardian reported that an account had "just reached London of how Miss Sheila MacDonald, a 22-year-old London girl, climbed the African mountain Kilimanjaro" - claiming that it was “the first time the feat [had] been accomplished by a woman".

In the following paragraph we learn of how MacDonald "set the pace for her two men companions, slept in caves, and sustained herself with champagne drunk from the bottle, and how, in spite of one of the men being forced to give up through physical exhaustion, she pressed on undaunted to the summit."

Only those who have done so can imagine how ludicrous one feels when trying to drink champagne out of a bottle at a height of over 19,000 feet.

It's a colourful picture - if one that perhaps overplays the part of the champagne.

Sheila MacDonald was born in Australia in 1901. Her father Claude was vice-president of the Alpine Club. She was educated in Cambridge, where she read Modern Languages and excelled in rowing. She climbed in Scotland, and beyond in the Alps, and was described by The Guardian as “a tall, well-built girl with shingled hair, who excels in outdoor games and horse-riding.” Before Kilimanjaro, MacDonald had also climbed Mount Etna (3357m) on the east coast of Sicily, and “with another girl risked an angry sea in a small open boat on their return from an ascent of Stromboli,” an active volcano in the Tyrrhenian Sea.

MacDonald travelled to Africa in July of 1927 by boat - but her intention was never to climb Kilimanjaro. The plan was to stay with her cousin, Captain Archie Ritchie, chief game warden of Kenya - and to go on safari. This plan was changed after a chance encounter with Mr. William C West on the ship to Africa, whom she had noticed was wearing an Alpine Club tie. Conversation revealed West was going to climb Mount Kilimanjaro - and he invited Miss MacDonald to join him.

“For heaven’s sake, you know nothing about my climbing ability,” MacDonald replied to the proposition. West replied: “I know your father’s reputation. I think that you could manage it quite well.”

For her part, MacDonald remembered her excitement after accepting West’s offer. “I collected a pair of trousers, socks, a wide-brimmed felt hat called a terai and a pullover - all from different passengers who were very interested in the venture - I only had boots to buy,” she told the Oban Times.

Major Lennox Browne, another passenger on the boat, asked if he could also join the party. “He had never done any climbing, but he felt that I should not be climbing as a lone woman with a single man,” MacDonald said, contradicting the later description of Lennox Browne as “a mountaineer of some experience” by various newspapers. The Major's reasoning for joining the trip is a reminder that this was a time when women often faced "social outcry" simply for hiking.

The party of three arrived in Mombasa on 21 July. MacDonald was immediately challenged by friends of her cousin Archie, who said she must travel on to Nairobi and “forbid” her to climb the mountain. Her parents, who expected her to stay with them in Australia after Nairobi, were similarly “shocked and furious”.

Regardless, the party travelled on to Marangu, in Tanzania, where MacDonald got her first sight of Kilimanjaro. She recalls a moment when West first told her they could now see the summit. MacDonald replied that she could only see clouds, to which West replied, "you’re not looking high enough."

MacDonald was astounded by the height. “It was tremendous,” she said. “I thought, ‘If I can get out of this, I shall’. But it was too late. It’s not a beautiful mountain. It’s rather like Ben Nevis; impressive by its immensity.”

The party began their hike to the noise of a kudu horn, sounded by the leader of a local village. They travelled through deciduous forest on elephant trails.

We went to the left round the crater rim and crawled to the summit, foot by foot. It really was like that. You can’t imagine the relief.

“The men were very courteous to me,” recalled MacDonald, in that same, fantastic Oban Times interview. “When we stopped for the first night, they said I was to have the tent, and they would just sleep out in their sleeping bags.”

The party hiked to the Bismarck Hut (2712m), passing antelopes in abundance, then on to Pieters Hut (3658m). They camped high on the north-west of the plateau. It was cold. A bottle of ink MacDonald had in her pack froze solid.

The party soon found a “remarkable and quite distinct natural rock staircase about two feet wide” which brought them to almost the top of the couloir beneath Mawenzi (5,149m), the second highest of the three peaks on Kilimanjaro. On the Mawenzi they found a food tin containing a list of those who had made it that far, and added their names.

“We celebrated our arrival with good wine drunk out of enamel cups,” said West.

The group returned to the Pieters Hut to rest before beginning their ascent on Kibo, the true summit of the mountain, the next day. They tried to find Hans Meyer’s Hole on the edge of the plateau, but failed, with West writing that, “our intrepid lady companion found another cave which satisfied her womanly instincts for comfort.”

The team began their summit push at midnight, but had only one lantern, which proved insufficient. West wrote: “there was no moon, and the darkness was so intense that it was thought inadvisable to continue.” The team huddled in a rock shelter until dawn.

Major Lennox Browne had to retire, “overcome by physical exhaustion” within 100 metres of the summit. West wrote that MacDonald “was undaunted and pleaded to be allowed to finish the ascent. Of course, I decided to carry on as well, but it was Miss MacDonald who set the pace when we started off again. It was a hard climb for a girl, but she stuck to it with wonderful grit."

MacDonald herself recalled the difficulties of the summit push herself, to the Oban Times: “After a good dose of whisky and lime juice, we reached the crater’s edge at Johannes Notch. We went to the left round the crater rim and crawled to the summit, foot by foot. It really was like that. You can’t imagine the relief of leaning up against the summit cairn and realising we were there.”

They celebrated, with West remembering that they “took one or two photographs, and drank a bottle of champagne,” adding, “Only those who have done so can imagine how ludicrous one feels when trying to drink champagne out of a bottle at a height of over 19,000 feet.”

It would seem that West was taking some storyteller’s liberties here. MacDonald later recalled that they “opened the [champagne],” but that "there wasn’t a drop left in it because of the altitude. Not one drop.”

She recalls the descent was easy, and within weeks, Sheila MacDonald - although little known today - was in newspapers around the world. “My friends were not in the least impressed,” MacDonald later said. “All they really thought about was that we had been through the jungle without firearms.”

Changing climates have made the ascent of Kilimanjaro easier today than it was in the 19th or 20th century, when snow lay thick and climbers risked blizzards.

The first recorded ascent of Kilimanjaro by either sex was made on 6 October 1889, when a team led by the German geologist Hans Meyer reached the summit. The first recorded woman to reach Mawenzi, the second highest peak, was actually the English mountaineer Gertrude Benham. Climbing in 1909, she ascended to the summit alone after her porters refused to go on - convinced of the “bewitched” nature of the mountain by two skeletons and the melting snow around a campfire.

It is unknown, of course, if an indigenous individual ever walked to the top of Kilimanjaro, far from the eye of the western media, but what is certain is that Sheila MacDonald would become the first known woman to summit Mount Kilimanjaro - and to drink, or at least open, a bottle of champagne on the peak.

MacDonald went on to travel back to Nairobi, where she did indeed go on safari with her cousin Captain Archie Ritchie. She married Harold Percy Combe in 1931, in what the Oban Times describe as a “brief and unsuccessful marriage”, later travelling to India and working in a hospital in London during the war. She eventually retired to the Highlands, in Lochaber, near Ben Nevis, where she painted. She passed away in 1987 and was buried in the foothills with a stunning view of Glen Spean, in a spot she had chosen herself a few months previous.

Inspired? Read the day by day itinerary for our summit trips up Kilimanjaro!