"Man is moved just like the ice floe, sailing here and there, out in the current,” said the Inuit poet and Shaman Orpingalik to polar explorer and anthropologist Knud Rasmussen, during Rasmussen's 18,000-mile crossing of the Northwest Passage in the 1920s. “Thoughts wash over him like a flood, making his breath come in gasps and his heart throb [...] and then we, who always think we are small, will feel still smaller. We will fear to use words, but it will happen that the words will come up of themselves, and when the words we want shoot up of themselves - we get a new song."

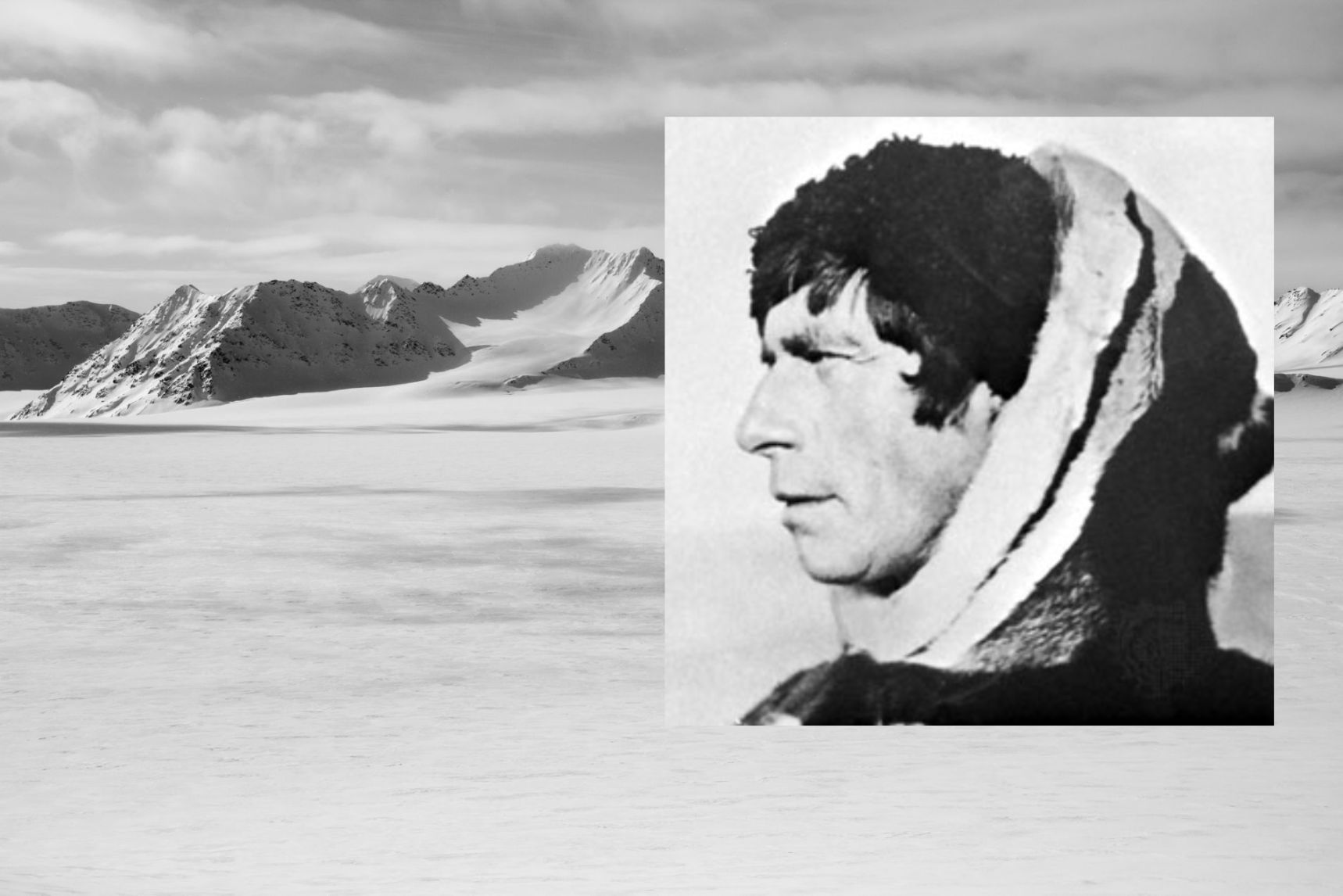

Knud Rasmusen is perhaps the most fascinating of all the great Arctic explorers, but he remains surprisingly little known to those without a keen interest in polar exploration or Inuit ethnology and literature.

The translations Rasmussen produced are likely never to be rivalled, and he set the standard by which all subsequent translations and collections of Inuit poetry are measured

Born in 1879 in Greenland to a Danish father and mother of Inuit origin, Knud grew up speaking both Danish and Kalaallisut, a language he would later discover was shared throughout the Inuit Arctic. He is unique in that his expeditions were not for the glory of conquering an unknown land, but rather, to find the native people who lived in the remote, harsh environments of the Arctic, and to document their cultures with humility, sympathy and respect.

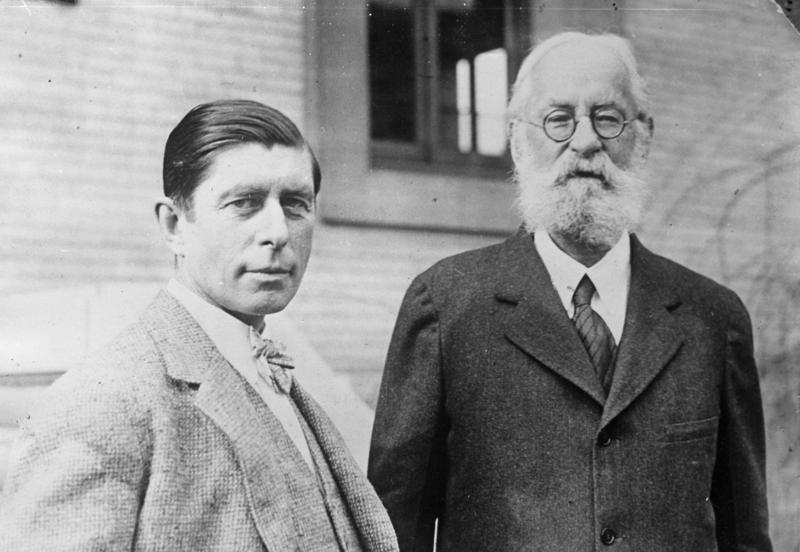

Stephen R. Bown, author of biography White Eskimo, wrote that Rasmussen had “an intuitive sense of human nature and a deep understanding of Inuit culture, not only the rituals and customs but also an insight into why [they] came to be.”

As a youngster Rasmussen learned Inuit survival skills and crucially, the art of dog sledding. He wrote in his 1927 book Across Arctic America that thanks to a childhood playing with native Greenlanders, "even the hardships of the most strenuous sledge-trips became pleasant routine for me."

He took to partying more than academia after moving to Copenhagen to study, but aspirations of being an opera singer fell aside when he went on his first expedition to study Inuit culture in 1902. Knud returned a celebrity, the Financial Times writing that at the height of his fame, "guards had to be posted at every door to keep his female admirers at bay" - though most of that fame would come after The Thule Expeditions for which he’s best known; a series of seven polar expeditions from 1912 and 1933.

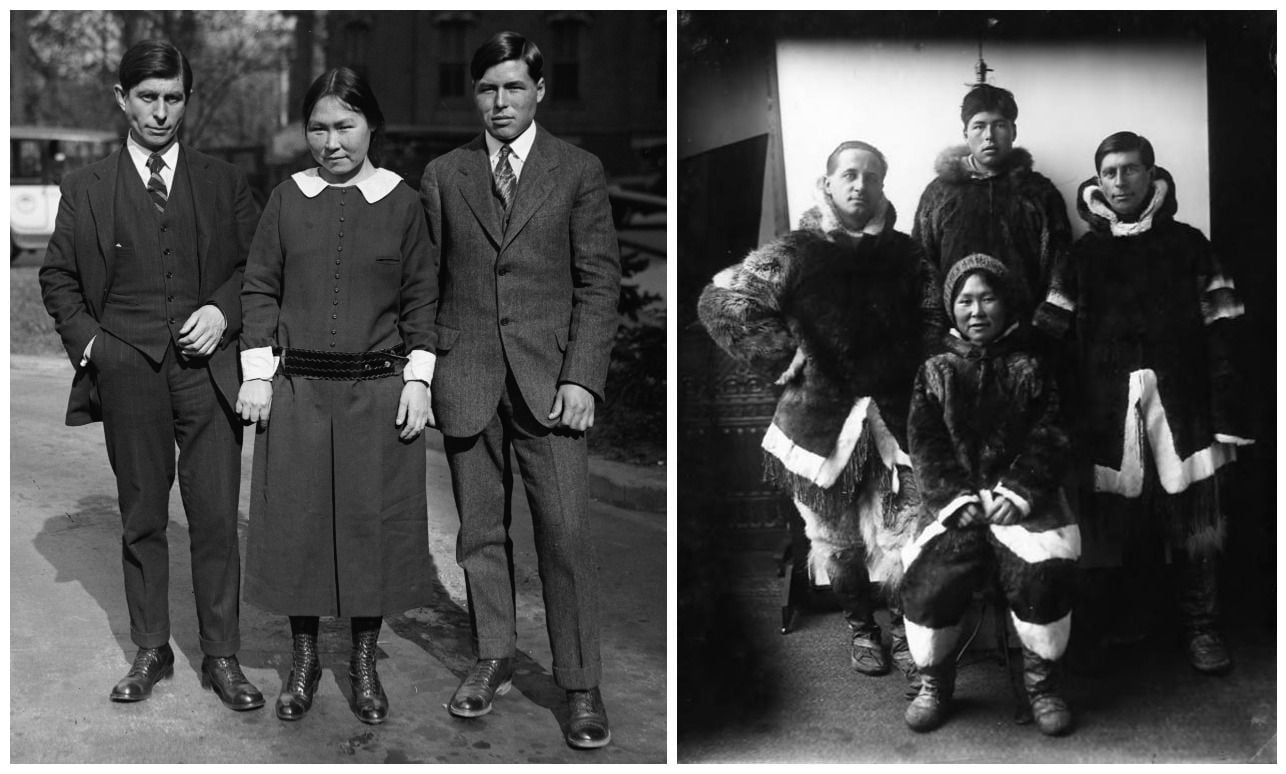

The majority of The Thule Expeditions were organised by Rasmussen and his friend and fellow explorer Peter Freuchen. With Knud five-foot-five and Freuchen six-foot-seven, the two cut quite the pair. The early expeditions focused on mapping parts of Greenland previously unvisited by Europeans, but it is for the Fifth Thule Expedition that Rasmussen is best known. Starting with a team of seven heading into Greenland, the expedition culminated with Knud becoming the first European to dog-sled the entirety of the Northwest Passage, dog-sledding over 18,000 miles from Eastern Canada to Eastern Russia along with two Inuit hunter companions, Mrs. Arnalulunguak and Mr. Meetek.

The polar journey took three years and only stopped in Russia due to visa issues.

From the Fifth Expedition Rasmussen produced an extraordinary collection of Inuit songs and legends from over 5,000 miles of Arctic coastlines, released across ten volumes between 1928 and 1945, several posthumously, as the explorer died aged 54 in Copenhagen in 1933. In his 1988 essay Reassessing Traditional Inuit Poetry, Robin McGrath writes that: “The translations [Rasmussen] produced are likely never to be rivalled, and he set the standard by which all subsequent translations and collections of Inuit poetry are measured."

While our own poets composed verses describing their feelings about the weather, Inuit poets believed that if they got the words of their poem just right, they could actually affect the weather

Penny Petrone, in her pioneering 1988 Northern Voices: Inuit Writing in English, wrote that "singing was as vital to life as breathing" to the Inuit people, noting that the oral song was part of every Inuk's way of life, and highlighting the words of the poet Orpingalik - "songs are thoughts, sung out with breath when people are moved by great forces and ordinary speech no longer suffices." The Inuk words for poetry and breathing even share an origin, "derivatives of anerca, the soul, that which is eternal: the breath of life," wrote E Carpenter in 1968.

Poetry served a practical purpose too. “While our own poets composed verses describing their feelings about the weather, Inuit poets believed that if they got the words of their poem just right, they could actually affect the weather,” writes McGrath. “Our nearest equivalent would be [...] prayer.” Petrone expands, writing that “the shaman's faith in his magic words was so enormous that he actually believed they had the power to stop the bleeding from a wound."

Rasmussen identified four categories of Inuit poetry: songs of mood (relationships), hunting (narrative), charm (focused on form) and derision (often satirical poems). No matter the category, they always involved the human condition - "poems about birth, work, sex, and death," writes McGrath - and nature was usually at the core of the creation too. McGrath writes “although these works frequently explore man's sense of fragility and insecurity, images of the land in Inuit poetry provide a sense of stability and continuity. The poet may be overwhelmed by the power of nature [...] but the land is always there.”

Perhaps the best known of these is 'The Song of Uvavnuk', sung by the shaman Uvavnuk after she was said to be struck by a meteor, her magical tale and poem told to Rasmussen by her relative Aua, who was also a spiritual healer:

The great sea

frees me, moves me,

as a strong river carries a weed.

Earth and her strong winds

move me, take me away,

and my soul is swept up in joy.

(Translation by Jane Hirshfield, Women in Praise of the Sacred, 1994)

Another beautiful example is 'Song Number 7':

My thoughts went constantly,

To the great land my thoughts went constantly.

The game, bull caribou those,

Thinking of them I thought constantly.

My thoughts went constantly,

To the big ice my thoughts went constantly.

The game, bull caribou those,

Thinking of them my thoughts went constantly.

My thoughts went constantly,

To the dance-house my thoughts went constantly.

The dance-songs and the drum,

Thinking of them my thoughts went constantly.

(Roberts and Jenness, 1925)

Michael P.J Kennedy writes in Inuit Folk Tales that "the advantage of having Greenlandic blood in his veins gave [Rasmussen] access, as well as status, as a collector of manuscripts and as a recorder of oral tales,” and that it was his “devotion to ethnography, as well as his sensitivity and curiosity that made Rasmussen the scientific and literary giant that he still is today.”

Perhaps the last word is best reserved for Rasmussen himself. On Inuk poetry, he wrote that: “these works don't arrive like fragile orchids from the hot houses of professional poets; they have flowered like rough, weather beaten saxifrage which has taken root on rock. And they ought to matter to us. For do we not hear through them something that reminds us of the original features of our own songs - the same teasing humour, the same quiet melancholia - and [...] a simple but grandiose pathos which grips us by virtue of its immediacy."

Inspired? Check out our 100km self-powered adventure across Greenland.