Cocaine for snowblindness. Ginger to prevent or relieve flatulence. Opium and chalk, mixed together, to combat the horror of diarrhoea. Cannabis and chilli peppers combined to treat colic. The contents of Antarctic medical kits have certainly come a long way since the days of Shackleton.

In 1907 Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton led his first of three expeditions to the Antarctic. The aim of the trip was to be the first expedition team to reach the South Pole. Shackleton and his team would eventually be forced to turn back just 97.5 nautical miles short of their target, but the mission was still widely considered a success. Shackleton, along with his fellow party members Eric Marshall, Jameson Adams and Frank Wild had set a new record for the most southerly point ever reached - surpassing Scott's record by a full 412 miles.

The bottle was sold by Burroughs Wellcome in the early 20th century and contained a powerful mixture of cocaine and caffeine. If taken once an hour 'when undergoing continued mental strain or physical exertion', it promised to prolong powers of endurance and curb appetites.

“It falls to the lot of few men to view land not previously seen by human eyes,” wrote Shackleton of the Nimrod expedition. “You can’t think what it’s like to walk over places where no one has been before.”

The feat is made all the more impressive by the humble gear available. Standard issue clothing would have been largely woollen clothing, fur mitts and leather hobnail, cotton-gabardine, or reindeer-fur finnesko boots - plus a Burberry cotton gabardine coat on top. The expedition team would've been wet, cold, itchy and chafed, almost constantly. Then there's the deep hunger felt by the party, which was eventually forced to turn back from the south pole because of a lack of food, and issues like snowblindness, fatigue and diarrhoea.

Ernest Shackleton’s medical kit for the Nimrod expedition was made by Burroughs & Wellcome Co. of London - and contained a variety of quirky treatments. The kit included a glass thermometer, bandages, plasters, safety pins, a tube of Hazeline cream (an emollient) and sewing needles, held together in a leather wallet (pictured below). There were also sixteen tubes of medicine.

Aspirin and morphine are two such treatments still recognisable in today's medicine, but also amongst the leather wallet was soda mint and cascara sagrada tablets, which were used as laxatives. Ginger was used to prevent or relieve flatulence. There were paregoric tablets, which the Science Museum describes as “a pain reliever made from an alcoholic preparation of opium”.

Dr. Gavin Francis notes in a Granta essay that “cocaine was dripped in the eye to cure snowblindness, and chalk ground up with opium was used for diarrhoea."

Francis highlights the inclusion of isinglass, prepared from the dried swim bladders of Russian sturgeons, and gold-beater’s skin, a “parchment-like dressing [...] prepared from the intestines of oxen or sand sharks”. Both were used on open wounds. There was a treatment for colic “that combined tincture of cannabis with tincture of chilli pepper” and tonics of iron and arsenic were carried, which could have easily killed someone if administered incorrectly.

Shackleton was actually ardently against the drinking of alcohol to excess, having grown up in a teetotal home, but he also brought 25 bottles of Rare Old Highland Malt Whisky on the Nimrod. “The popular idea of the time was that whisky and brandy had medicinal value,” writes Neville Peat in his book Shackleton's Whisky. “If you were cold, alcohol could warm you up, and a hot toddy was just the thing to combat the common cold.”

Shackleton’s decision to turn back when he did showed remarkable courage and intelligence. It is for reasons such as this that he continues to be so revered.

Perhaps most intriguing of all were the Forced March tablets which were used both by Shackleton and Scott. Forced March tablets were made from a combination of cocaine and caffeine. The idea was to provide a boost to anyone drastically in need of some energy. The Lancet write that “the bottle was sold by Burroughs Wellcome in the early 20th century and contained a powerful mixture of cocaine and caffeine. If taken once an hour 'when undergoing continued mental strain or physical exertion', it promised to prolong powers of endurance and curb appetites.” On the Nimrod expedition, the tablets were used on the return trip.

Before Shackleton was forced to turn back from his south pole attempt, the team became the first people to set eyes on the Transantarctic Mountain Range, and to find a navigable way through it. They would also achieve the first ascent of Mount Erebus, Antarctica's second highest volcano. The failing of the mission was down to a lack of food. Had the crew carried just 25lbs more biscuits and 30lbs of pemmican (a mix of dried meat, fat, and cereal), or had their pony 'Socks' not tragically fallen to his death in unpreventable circumstances days earlier, it’s likely that the expedition would have actually reached the pole.

“Shackleton’s decision to turn back when he did showed remarkable courage and intelligence,” writes Antarctic explorer Ranulph Fiennes, in his biography Shackleton. “It is for reasons such as this that he continues to be so revered.” But Ernest now faced a walk of hundreds of miles just to get back to the Nimrod.

With the wind behind them, Shackleton - increasingly frostbitten - had the idea to fashion the floor cloth of a tent into a sail for the party's sledges. This allowed the team to harness the power of the wind and ease the fatigue of their return trip. Still, they were drastically low on food and energy.

As they strived to reach the nearest depot - a rest point, where a top-up of food awaited - the group were on the cusp of death. They had even finished the maize and pemmican meant for their pony. At this point Marshall, the expedition's surgeon, surveyor and cartographer, produced a set of Forced March tablets.

In his book Shackleton's Forgotten Expedition, polar historian Beau Riffenburgh writes that "Marshall dosed his party with the 'Forced March' tablets, and each hour they were slightly revived and able to crawl on."

At 10pm they added a cup of cocoa to the tablet, but by 2am the tablets were finished, and "the men were falling asleep on their feet." Frank Wild, one of the expedition members, later wrote that "whilst hanging in the harness I prayed that the rope would break so that I should have a nice long rest."

The party were forced to camp three miles from the depot due to fatigue. They had not had any food for over 30 hours, and Shackleton himself wrote: "I cannot describe adequately the mental and physical strain" of one of "the hardest and most tiring days we have ever spent in our lives."

Marshall's “dark mood had permeated much of the march" so far, writes Fiennes, but in this moment, he stepped forward as an unlikely hero. Marshall knew that only he had the strength to go on to the depot and bring back food for the others. Within 25 minutes, Marshall did indeed reach the depot, where he ate two lumps of sugar to satisfy his own hunger, and then returned to the party with rations. He later wrote: "If I was asked to choose between the relative merits of Forced March or sugar, under similar conditions, I should choose sugar."

They cooked hoosh (a thick stew made from pemmican) and horsemeat with their renewed supplies, having consumed nothing other than Forced March and cocoa for 36 hours. Wild wrote that it was the “finest meal we had ever tasted.”

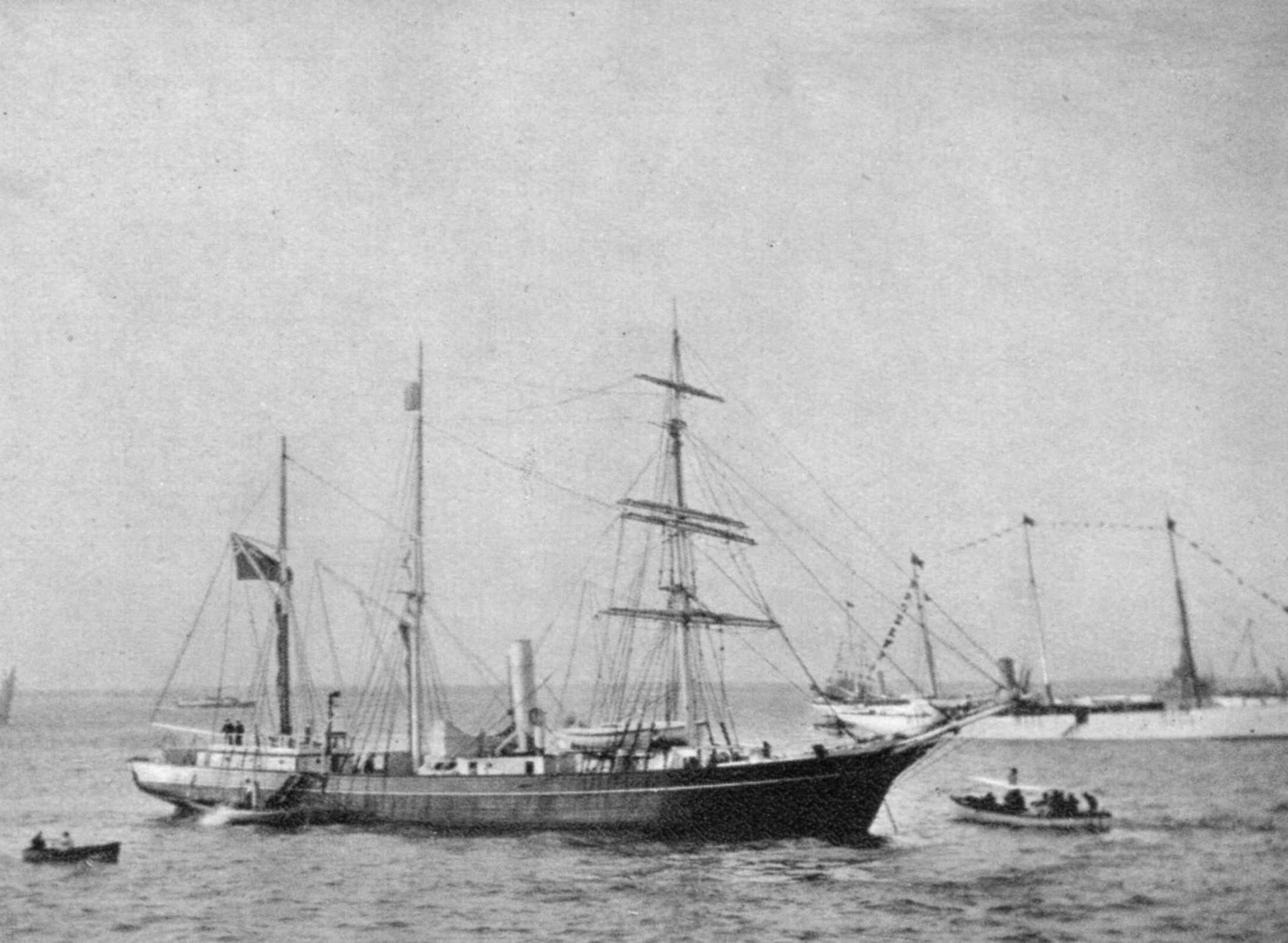

The days that followed brought further hunger and peril in abundance, but by 3 March 1909, the party were safely back on the Nimrod, having narrowly avoided starvation and fended off near certain death in Antarctica. That conspicuous blend of caffeine and cocaine may just have helped the group survive, but if Marshall is to be believed? They would have been better off sticking to sugar.

Fancy an icy expedition of your own? Check out our 100km self-powered adventure in Greenland or adventures in Svalbard!