We paddled our kayaks through a river fringed with mangroves. The branches arched over the water making a natural roof, the foliage filtering out the heat of the day. Silence, except for the paddles dipping in and out of the water and the occasional cry of a bird. The smell of salt and mud in my nostrils. Aside from our group, there wasn’t a person in sight.

This wasn’t an expedition into a remote, tropical rainforest. We were paddling through the mangroves on Koh Yao Yai, an island in south Thailand, one of the world’s most visited countries. In 2023, Thailand saw in excess of 28 million tourist arrivals, many of whom flock to the karst islands and white sand beaches of the south for a break in the sun. I had escaped the grey dreariness of a British winter for those exact reasons - only I wanted to experience Thailand away from everyone else.

Thailand has a reputation for being a budget backpacking destination. In 2018, Maya Bay on Koh Phi Phi - made famous by hollywood film The Beach - was closed to recover from the environmental ill effects caused by visits of around 6,000 tourists a day. It has since reopened, with reduced numbers allowed. Meanwhile, last year Koh Samui hit the headlines when overtourism led to a dramatic drop in the island’s water reserves.

But there’s always more to a country than the images of it on social media and in the news. Last year I visited Gran Canaria, a country known for mass tourism - but heading inland I discovered ancient cave houses and hiking trails snaking through rocky mountains and lush ravines, with barely a tourist in sight. Would adventure tourism be able to show me ‘the road less travelled’ in Thailand too? I packed my hiking boots and headed there to find out.

Our trip started in Bangkok, where we eschewed the backpacker hangout of Khao San road for Chinatown. It’s one of the oldest areas in the city, founded in 1782 when the Chinese immigrant community was relocated for the building of the Grand Palace. The heart of modern day Chinatown is Yaowarat Road, a busy neon-lit thoroughfare lined with jewellery shops and Chinese medicine stores - its curves are said to resemble the body of a dragon. Small alleyways extend off it, selling everything from tropical fruit to used car parts. Getting lost in the hubbub is part of the fun - and trying the delicious street food, a blend of Chinese and Thai cuisine.

The best time to do this is after 6pm, when the streets close to traffic and hawkers open up their stalls. The air is thick with the aroma of charcoaled pork and frying garlic; filled with the sound of ladles clanging, the sizzle of hot oil and hawkers shouting out their wares. Crowds throng the street in search of their next meal - but you'll find more locals than tourists. I had grilled chicken skewers with a punchy satay sauce and pickled cucumber, followed up with a chicken and glass noodle soup (suki yaki). I also sampled kanom krok, coconut milk pancakes, and tofu ice cream - all equally delicious.

The air is thick with the aroma of charcoaled pork and frying garlic; filled with the sound of ladles clanging, the sizzle of hot oil and hawkers shouting out their wares

The next day, we caught a boat across the Chao Praya River to Bang Krajao, a river island nicknamed the ‘green lung of Bangkok’. As we set off to explore, on bicycles hired from the jetty, it soon became apparent that it lived up to this moniker. In the cool of morning we pedalled along asphalt paths that wound through lush forest, and across wooden boardwalks spanning a small lake. At this point in the day we were one of the only groups on the trails - and able to find some peace in this frenetic city.

After circumnavigating the park we explored the island via a series of narrow, elevated concrete paths that wound through mangrove forest, past small fields cultivated with vegetables and banana palms. Many of the restaurants and homestays serve these homegrown fruits and vegetables, and they’re also displayed in the local floating market, where we stopped for a break. We browsed the street food stalls, sampling sticky rice cooked inside a bamboo tube and snakeskin fruit, among other things.

This didn’t quite spoil our appetite for lunch, but it was a close call. We ate our first full Thai meal at the Ozone Cafe, in thatched bamboo huts overlooking the river. Seafood tom yum (a tangy soup) and larb, spicy minced pork with fragrant herbs, were two of the standout dishes.

That evening we caught the night train to Surat Thani; an experience in itself. The carriage was divided into compartments, each occupied by two people. When we were ready to sleep, we called the conductor who pulled down and attached a top bunk, and made the two seats into a bottom bunk. I drew the curtains and was lulled asleep by the rocking motion of the train, only waking up when our guide, Rit, told us that our stop was next.

Islands jutted out of the turquoise water - some low-lying and carpeted in forest, others jagged karst formations

Surat Thani. A station full of bleary-eyed, confused-looking tourists. Without Rit we would have been among them too. We detached ourselves and headed on our way. The next stop: Cheow Lan Lake, in Khao Sok National Park, which preserves one of the oldest swathes of rainforest in the world.

The lake was created in 1987, when the Thai authorities built the Ratchaprapa Dam, an electricity-generating project that diverted the Klong Saeng River and created a 71-square-mile lake. As the basin flooded, 385 families from the area were resettled, and over 1000 stranded animals needed to be rescued.

This turbulent history was not apparent as our longtail boat skimmed across the lake. Islands jutted out of the turquoise water - some low-lying and carpeted in forest, others jagged karst formations. It wasn’t long before we disembarked at a raft of floating bungalows, each with their own wooden jetty, and a double kayak moored to each one.

Cheow Lan is a popular tourist spot, but due to the size of the lake it doesn't feel overly crowded. And thanks to Rit’s logistical know-how, we were the first arrivals and had several hours to enjoy the solitude. We swam in the cool water and tested out the kayaks, enjoying the freedom of exploring our surroundings unguided.

Later, we travelled by longtail boat to a nearby island. We followed a dirt trail into the jungle, passing through clumps of bamboo, twisted liana vines and banyan trees with huge buttress roots. Our guide pointed out a troop of monkeys swinging through the tree canopy; he showed us a carnivorous pitcher plant, which flowers with colourful ‘pitchers’ filled with liquid that will dissolve the insects who fall into it.

The path rapidly became steeper. Sweat poured off us as we climbed, using slender tree trunks to pull ourselves upwards. The end of the hike involved an exciting scramble over limestone, searching for handholds and footholds in the smooth rock. But the view from the top, over a lake studded with islands, was more than worth it - and there wasn't a tourist boat in sight.

Several days later we had our first kayak expedition in Than Bok Khorani National Park, in Krabi province. Less visited than Khao Sok, it’s equally beautiful. An emerald river, water cloudy with calcified limestone from the nearby mountains, winds through mangrove forest and inside caves. After feeding the fish for good luck - an important start to any kayaking adventure - we set off.

An emerald river, water cloudy with calcified limestone from the nearby mountains, winds through mangrove forest and inside caves

We glided down a tree-lined river, past steep limestone mountains. Every now and then we encountered other groups - many of whom were leaning back in their seats and allowing their guides to do all the paddling. However, we were alone in the two caves we paddled into, Tham Lot and Tham Pee Hua Toe, where twisted stalactites hung from low curved roofs. Tham Pee Hua Toe translates to ‘big-headed ghost cave’ - it was likely a burial site around 3000 years ago, as a number of large skulls were found there. Our kayaking guide shone his torch over rock paintings on the cave roof and walls - vestiges of an ancient presence.

One of the busiest places we visited was the Tiger Cave Temple, located on top of a limestone peak around 270 metres high, reached after a climb up 1260 stone steps. At the base is a religious complex, where Buddhist monks still live and pray, and which includes a natural cave system. A monk went to meditate in the caves in 1975, returning with tales of roaming tigers, which is how the place got its name.

We had begun our hike early, soon after breakfast, but the sun was already fierce. We gasped our way up a series of steep stone staircases, stopping for frequent water breaks. There were plenty of people undertaking the climb alongside us, both locals and tourists; those coming down the steps gave us sympathetic smiles.

A meeting with a troop of overly-assertive monkeys - who tugged at our bags in search of food - gave us the adrenaline rush we needed to reach the top. The last step led us out onto a broad tiled platform encircled with a stone balcony. In the middle of the platform, a large golden Buddha statue gazed with a serene expression at the mountains and fields below.

The scene on the way back down was nowhere near as tranquil. We encountered a group of school children, teacher-less and reduced to tears by the monkeys. Despite the language barrier, we were able to help them back down the stairs. When one of the monkeys threw an empty bin at us, one of our group stopped it barrelling down the steps towards the children.

By the time we finished the hike, my clothes were so drenched in sweat I had to buy a new outfit from one of the stalls at the bottom. Refreshed with tender coconut water, we headed to Huay Toh, a multi-tiered waterfall where we found a natural swimming pool just for ourselves.

That night, we spent a couple of hours in the town of Ao Nang in Krabi, kicking off with a sunset cocktail overlooking the beach. It was admittedly beautiful, but much more crowded with backpackers than anywhere we'd been previously. And it was tourists who thronged the night market, rather than locals - pizza and jacket potatoes were being sold alongside Thai food. I imagine, after months travelling, such food is a welcome comfort - but I eschewed it in favour of crab and betel leaf curry.

Ao Nang was a stark contrast to the time we spent on Koh Yao Yai. Thailand’s islands attract millions of tourists each year, but few of them go to Koh Yao Yai, despite its convenient location in between Phuket and Krabi. The majority of the island’s population are muslim - they don’t want their home to become another party island, preferring to preserve their environment and traditional way of life. Because of this, the island remains relatively undeveloped, with locally-run homestays and restaurants, and not a nightclub in sight. It was exactly what I’d been looking for - and it didn’t disappoint.

We were met by our guide Mr Bang Ya (‘ya’ means ‘medicine’), who greeted us with a smile and took us to Laem Had Beach, a strip of gleaming white sand fringed with coconut palms, the northernmost tip of which tapered into a sandbar that disappeared into the water. We were only the second group to arrive - a stark contrast to Ao Nang - and grabbed a patch of shade under the coconut palms, heading to the ocean for a dip whenever we got too hot.

As we paddled the foliage grew denser, and the river narrowed until it was barely a metre wide

Later, we headed off on our kayaking trip through the mangroves in the island’s interior. As we paddled the foliage grew denser, and the river narrowed until it was barely a metre wide in places. This time, there was nobody there but us.

We navigated past a tangle of prop roots jutting from the water, occasionally getting our paddles stuck on them. For the second time we encountered a troop of monkeys, clambering and swinging through the mangroves after us. These ones were much more agreeable, however - probably because the guides had brought along some bananas, which they threw into their outstretched hands.

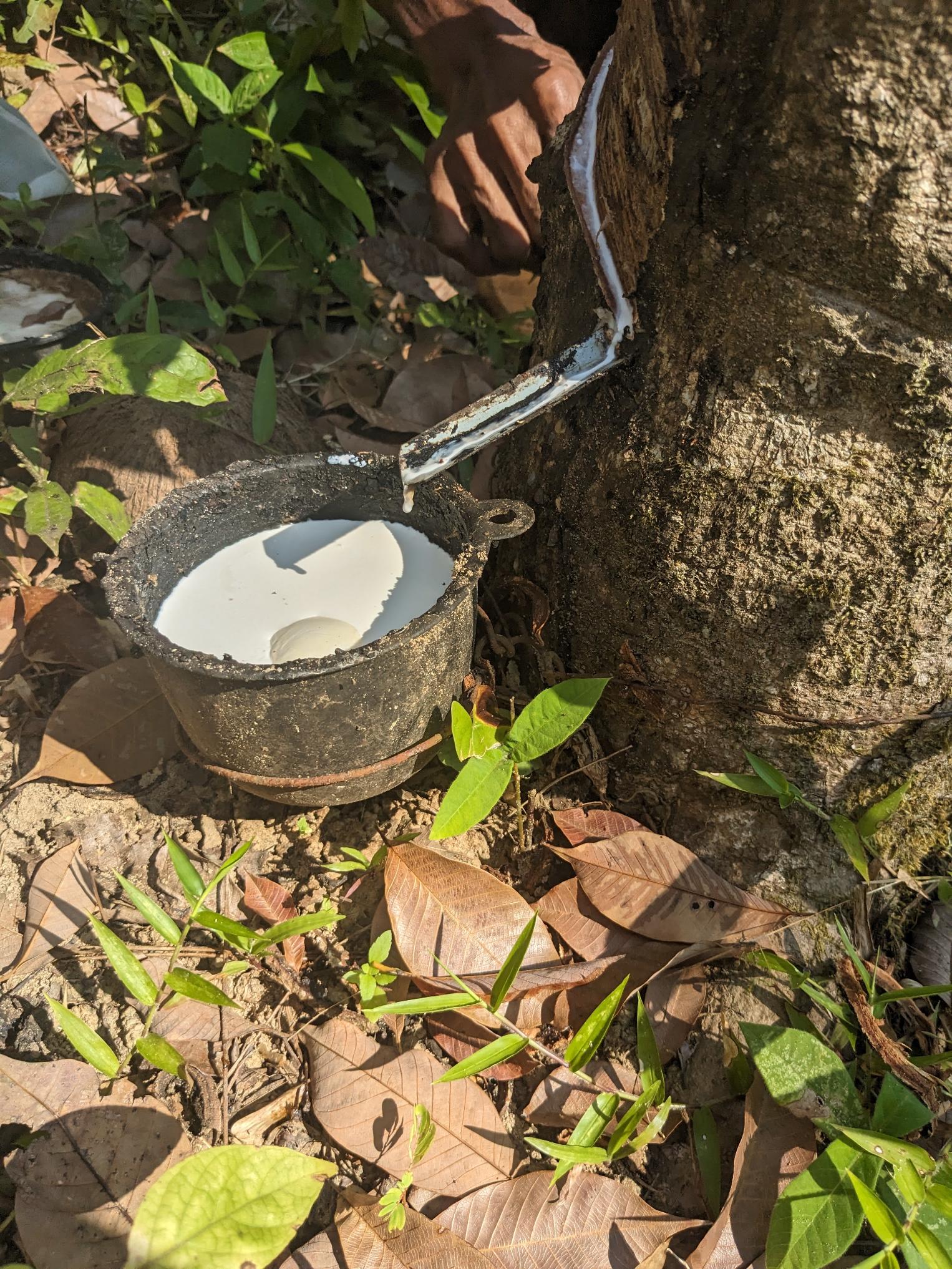

Our second day on Koh Yao Yai we met Mr Bang Ya at a junction on a dirt road. He handed us all catapults - we’d need them later, he said. Tucking them into our pockets, we followed him down a dirt trail into the forest. After a few minutes we reached a slope where slender trunked-trees were spaced at regular intervals. Many of them had a narrow channel carved into them, which spiralled down the trunk and ended with a small metal gutter. Bright white liquid trickled down it and dripped into a bucket below.

These, Mr Bang Ya told us, were rubber trees, and natural latex was being collected from them. The latex would then be sold to rubber processing plants - but sale prices have decreased in recent years, making it increasingly difficult to make a living from rubber tapping.

We continued walking. Mr Bang Ya pointed out some larger trees - their latin name is dipterocarpus alatus but they’re known colloquially as resin trees, thanks to the oily sap that they produce. The resin was traditionally used by the villagers of Koh Yao Yai in torches, and as waterproof sealant for their boats. But in recent years it has rocketed in value - it can be used as fuel for diesel engines, varnish for furniture and in zinc-based paint.

To harvest the resin, a part of the tree must be slowly burnt - but there was only one woman on the island who still had the knowledge to do it sustainably, Mr Bang Ya said. He showed us a tall tree with a charcoaled hole in the trunk - and the scar tissue on the bark from previous burns, now healed over. He told us that he’d inherited a section of plantation years ago and had cut down the resin trees and sold them for timber - something he regretted now.

To harvest the resin, a part of the tree must be slowly burnt - but there was only one woman on the island who still had the knowledge to do it sustainably

A few minutes later, we stopped in a sunny clearing at the top of the hill. Mr Bang Ya pulled a bag of seeds out of his pocket. These were from the resin tree, he told us. He showed us how to load them into our catapults and fire them into the foliage.

I took a handful of the seeds, which were the shape and size of gobstoppers. I hooked the first one into the catapult and stretched the elastic tight. Released it, and watched the seed arc through the clear sky. In the silence of the forest, I heard the thump as it hit the ground. Maybe, hopefully, it would take root.

Inspired? Check out our Kayak and Hike Wild Thailand adventure.