The recommended route for canoeing the Great Glen Canoe Trail runs from west to east, from Fort William to Inverness, as this gives you the greatest chance of catching a south-westerly tailwind and relieving some of the (sizeable) effort of the paddle strokes. Of course, the wind in Scotland is famously changeable, but as we paddle slowly along the southern shores of Loch Ness, we catch that tailwind, and for a moment, the pressure of the oars eases. We cruise by little beaches backdropped by water, and the sun shines down on this monster of a loch.

The Great Glen Canoe Trail is a route of wild camping nights, of midge dodging and café chasing - and of rolling, layering, rugged Highland scenery which reflects back off the water. It’s a rare chance to paddle from the Atlantic Ocean to the North Sea, but it’s also a route which was only made possible only in the 19th century - by the ingenious creation of the Caledonian Canal.

The rise in tourism is hardly surprising for a canal set in such spectacular scenery, rich in ruined castles and romanticism...

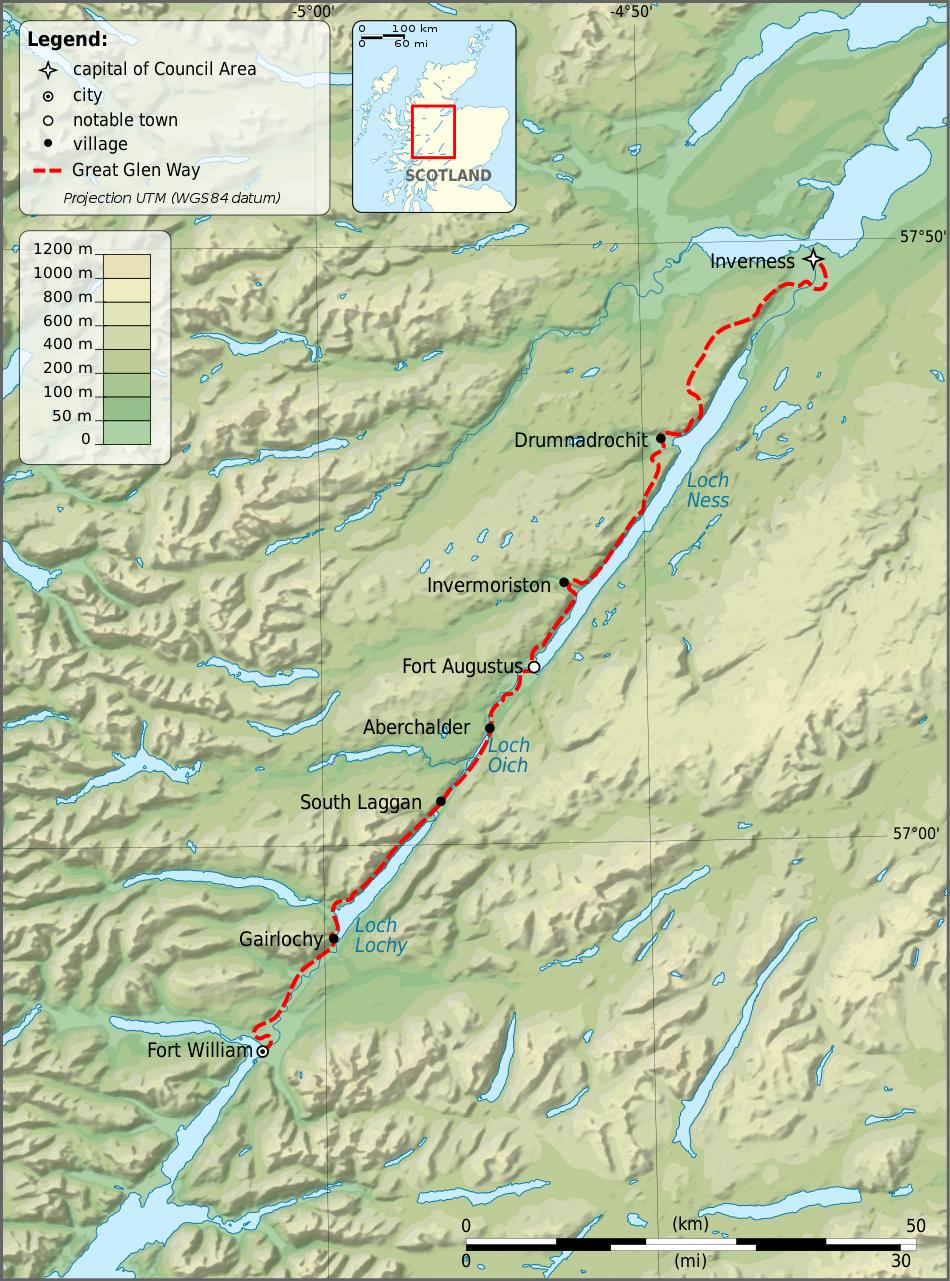

One of the great engineering projects in the history of Scotland, the Caledonian Canal runs for 60 miles (only 22 of which are manmade) through the Great Glen, connecting Loch Linnhe and Fort William, beneath Ben Nevis, on the west coast of Scotland, to Inverness and the Beauly Firth on the east. By doing so, it creates an entirely sailable route through the Scottish mainland.

The canal was constructed in the early nineteenth century by the pioneering engineer Thomas Telford for exactly this purpose - creating a safer shipping route to the arduous, often perilous journey around the north of Scotland via Cape Wrath and the infamous Pentland Firth.

It was built along the Great Glen, on a geological fault in the Earth's crust easily visible on the map of Scotland, and was completed in 1822. Telford served as the principal engineer throughout. It remains a huge attraction today not just for that feat of engineering - which includes Neptune's Staircase, the longest staircase lock in Britain - but also for the fact that it happens to provide a sublime route through some of the best scenery in Scotland, connecting Loch Lochy, Loch Oich, Loch Ness and Loch Dochfour with one another, and then in turn, connecting with the sea at either end.

As such, the route has become a favourite with walkers, cyclists and in particular, with paddlers.

The Great Glen Canoe Trail is arguably now the best known long-distance canoe trail in the United Kingdom - taking paddlers 60 miles through lock gates and remarkable Scottish scenery.

Caledonian Canal: Map & Pub Quiz Cheat Sheet

The above is a hiking map for the Great Glen Way, which travels the length of the Caledonian Canal, starting in Fort William and ending in Inverness. Of course, only 22 miles of this route is actually manmade, and the route runs slightly longer than 60 miles when you walk or cycle it rather than canoeing it - which we would say is the best way to experience the route.

- How long is the Caledonian Canal? 60 miles (22 of which are manmade).

- Where does the Caledonian Canal start and finish? Fort William and Inverness.

- Who built the Caledonian Canal? Civil engineer Thomas Telford.

- What is the hiking route on the Caledonian Canal? The Great Glen Way.

The History of the Caledonian Canal

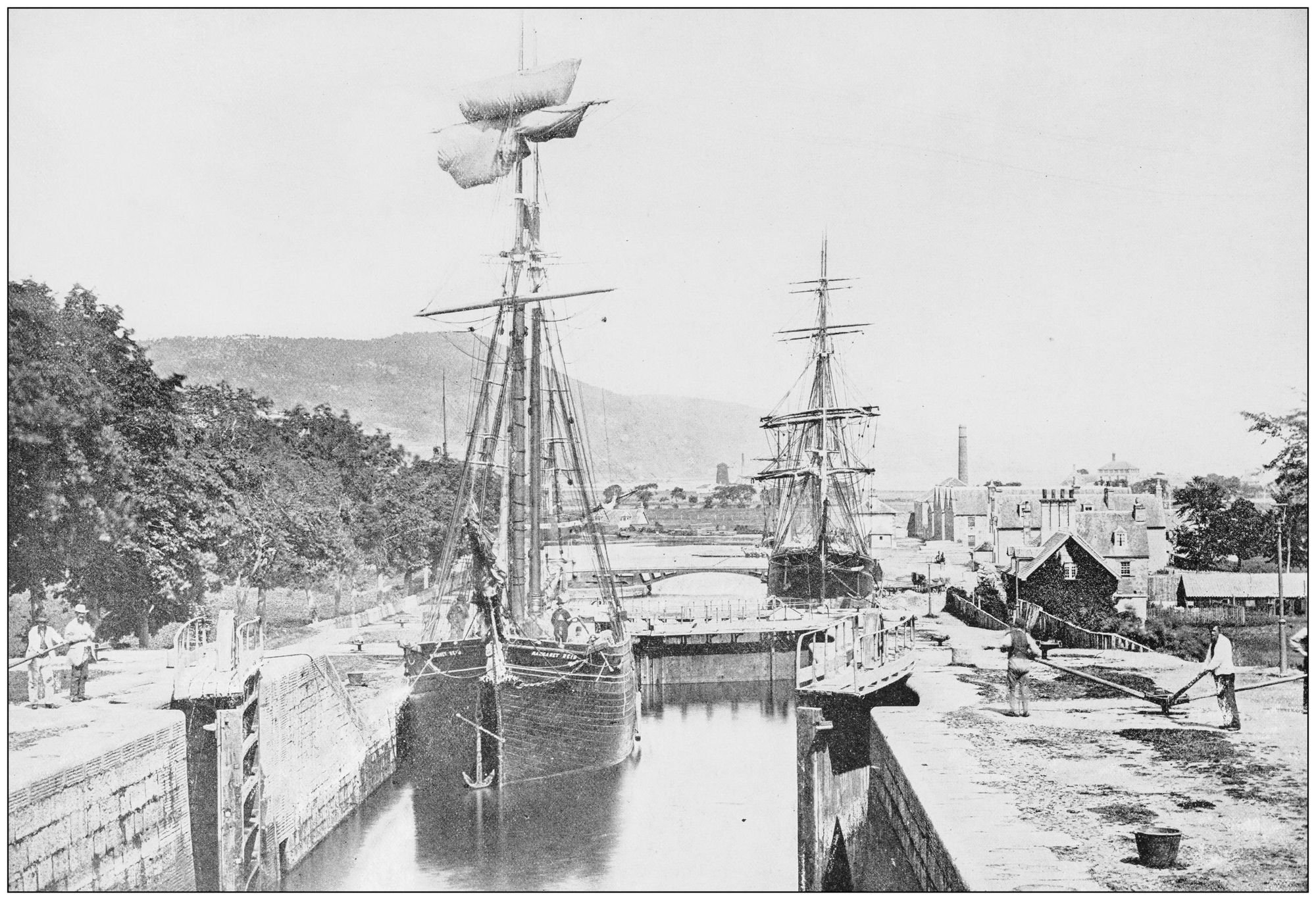

The first ship sailed from Inverness to Fort William, through the Caledonian Canal, over the 23rd and 24th of October 1822. The Inverness Courier reported on the event, writing that “the doubters, the grumblers, the prophets and the sneerers, were all put to silence, or to shame; for the 24th of October was at length to witness the Western joined to the Eastern Sea.”

The newspaper describes the “hearty cheers of the crowd of Spectators assembled to witness the embarkation, and a salute from all the guns that could be mustered.” It talks of how “neighbouring hamlets poured forth their inhabitants” and conveys how “at every inlet and promontory, tributary groups from the glens and the braes were stationed to behold the welcome pageant, and add their lively cheers to the thunder of the guns and the music of the Inverness-shire militia band, which accompanied the expedition”. The reaction sums up the weight of the accomplishment - and the surprise amongst many that the project was a success.

The Early History

Indeed, the Caledonian Canal had been a long time coming. It was predicted as early the 1600s, by the prophet Brahan Seer, that “the time will come, and it is not far off, when full-rigged ships will be seen sailing eastward and westward by the back of Tomnahurich at Inverness.”

The idea that Loch Linnhe, the sea loch by Fort William, could be connected to the Moray Firth by Inverness was first seriously explored in the late 1700s - by which point work was already ongoing on a sea-to-sea canal between Edinburgh and Glasgow (the Forth and Clyde Canal).

What loch could compare with Loch Ness in length or in depth?

The reasons why this particular route was attractive are outlined by the historian A.D. Cameron in his excellent history The Caledonian Canal, which was published for the 150th anniversary of the canal in 1972 and remains in print, several editions later. Cameron writes:

“At the time, the cry everywhere was for canals and the Great Glen running from south-west to north-east from Fort William to Inverness looked as if it had been shaped by nature to make the canal-builder’s job easy. Where else in the mountainous country in Britain was there a stretch of sixth miles involving a rise above sea level of only about a hundred feet? Which other area contained three long narrow lochs in a straight line capable of forming two-thirds of the heavy rainfall to swell the mountain streams and keep the water level high? What loch could compare with Loch Ness in length (22 miles) or in depth (129 fathoms), deeper than any part of the North Sea between Scotland and Denmark?”

It was in 1774 that James Watt - the inventor and engineer whose 1776 steam engine would be fundamental to the Industrial Revolution - compiled a report outlining how a three metre (10ft) deep canal from Fort William could be built, connecting Loch Lochy, Loch Oich, Loch Ness and Loch Dochfour, and emphasising the benefits for the fishing industry. He believed it would require 32 locks and around £164,000 - though he also worried wind could make it difficult.

But it was what Cameron describes as “the Highland problem” that really drove forward the plans for the Caledonian Canal.

After the second Jacobite uprising ended with a brutal defeat for the rebels at Culloden in 1746, Highlanders were banned by law to “carry weapons, wear tartan or even play the bagpipes”, Cameron writes. The Highland Clearances - during which natives were evicted from their ancestral land to make way for lucrative sheep farms - led many to emigrate to Canada or the Central Belt of Scotland. There were few opportunities for Highlanders and after crop failures in 1799 and 1800, there were few reasons to stay - so many simply didn’t.

The government was concerned at this loss of manpower, and was seeking a way to address it, and to bring the Highlanders work. It was before this backdrop that Thomas Telford, in 1801, was asked to investigate whether it was practical to cut a canal through the Great Glen.

Thomas Telford and the Caledonian Canal

Thomas Telford was born in 1757 near Langholm, a picturesque town in Dumfries and Galloway. He worked on bridges in the town that still bear his name today. By 1801, he had worked on the aqueducts of the Ellesmere Canal and stunned Londoners with a plan for a single-span iron bridge across the Thames. When he was called upon to plan the Caledonian Canal, Telford responded with fervour. In a letter written in 1801, he described it as “one of the noblest projects that ever was laid before a Nation, the whole of which I am satisfied is practicable.”

The engineer was also asked to survey the potential use of such a canal in Britain’s ongoing wars with France (though by the time it would eventually open, this reason would be defunct, with Napoleon being defeated at Waterloo in 1815, some seven years before the canal opened).

For the waterborne tourist there is the added buzz that Nessie, the Loch Ness Monster, might just break surface and make the photographer famous.

Telford was not the first person to believe in the feasibility of the canal, as aforementioned, but the difference was that his survey and subsequent proposal was commissioned by the Treasury.

The engineer believed that the canal could be built in seven years for £350,000. The project was authorised by parliament on 27 July 1803. The final construction would feature 29 locks - devices used for raising and lowering boats - four aqueducts and 10 bridges. Clachnaharry Lock, west of Inverness, was the first to be constructed, and was operational by 1807.

“The scale of the Canal from sea to sea was determined by the size of ships that sailed the sea,” writes Cameron. “It was to be a ship Canal [...] The proposed locks were to be 162 feet long and 38 feet wide, big enough to accommodate all the Baltic and West India vessels.”

Some of the most notable feats of engineering can be seen at Neptune’s Staircase, which comprises eight locks at Banavie, near Fort William, making it the longest staircase lock in Britain to this day. Telford and his consulting engineer William Jessop decided to use cast iron swing bridges in order to avoid damaging ship masts. The staircase raises the canal by 19m (26ft) over a quarter of a mile of masonry. Initially hand-powered, today it's hydraulic operated.

The canal was completed as far as Loch Lochy by 1816, by which point the level of the loch needed raised, and in the great tradition of British infrastructure, the full project took five years more than anticipated and cost over twice the estimated price. The Caledonian Canal finally opened in 1822, at a cost of £840,000-£910,000, with the help of over 3,000 local workers.

The canal played a crucial part in material transport for mine construction during WW1, and, Cameron notes, “ships on Government service again resorted to the Canal in considerable numbers to take advantage of the safe passage from sea to sea.”

In 1962, the ownership of the canal was transferred to the newly created British Waterways and mechanised, and from 1995-2005, major restoration work took place.

Today, the Caledonian Canal is a Scheduled Ancient Monument, and fishing boats and pleasure cruises still use the waters daily. The canal now welcomes over half a million visitors each year - many of whom set out to hike, cycle or paddle the length of the canal.

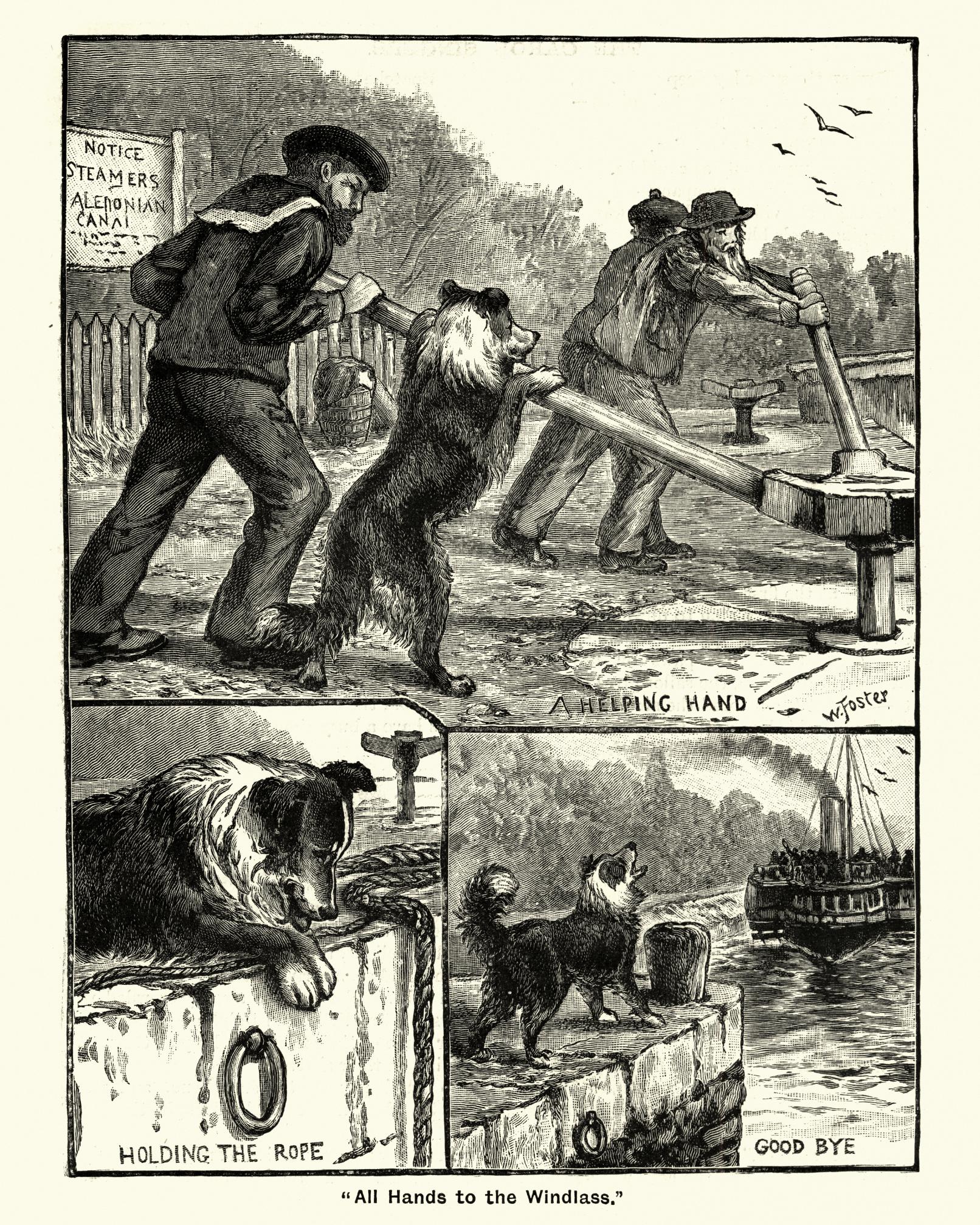

Writing in Caledonian: The Monster Canal in 1992 Guthrie Hutton notes: “The rise in tourism is hardly surprising for a canal set in such spectacular scenery, rich in ruined castles and romanticism. For the waterborne tourist there is the added buzz that Nessie, the Loch Ness Monster, might just break surface and make the photographer famous. In all this magnificence and mystery, it is easy to forget those early nineteenth century pioneers who moved mountains, raised lochs and changed the course, not just of rivers, but of history too.”

Paddling the Caledonian Canal: The Great Glen Canoe Trail

Length: 60 miles (96km)

Days: 3-5 days

The best way to experience the Caledonian Canal for yourself is from water level, on perhaps the UK’s most famous water-based adventure route - the Great Glen Canoe Trail.

Launched in 2012, this legendary canoe route will take you the length of the Caledonian Canal. As we mentioned in the introduction, it’s best to start in Fort William and head northeast to Inverness, to give yourself the best chance of a tailwind. There are 29 locks, of course, which you’ll have to portage around (meaning, you need to carry the canoe). For this reason, you’ll usually start this route in Banavie, above Neptune’s Staircase, avoiding eight locks.

The first seven miles (11km) of canoeing will take you to Gairlochy. From here, it's 15 miles (25km) through the length of Loch Lochy. This may sound like it was named by a child but it’s actually an anglicisation of the Gaelic Loch Lòchaidh, which translates to English as Loch Dark Water.

Passing through the Laggan Locks, it’s then on to Loch Oich, where it’s wise to seek another camping spot. Portaging around the lock gates at Cullochy and Kytra, you'll then reach Fort Augustus, before paddling through the legendary Loch Ness on a 15 mile (25km) stretch, all the while surrounded by truly superb panoramas of the layering Highland hills and water.

We should note that both Loch Lochy and Loch Ness are Class C waters, which means the terrain will be similar to being at sea, with cold waters and potentially challenging paddling - often with sizable waves. You'll pass Urquhart Castle and Drumnadrochit ion a 13.6 mile (22km) paddle as you head to the head of Loch Ness, and after another camp, it's a simple 6.2 miles (10km) to Inverness, via Loch Dochfour and the final stretch of the Caledonian Canal.

The beauty of canoeing this route is that you’ll take in both narrow stretches of river lined by dense forests, and huge bodies of water like Loch Lochy and Ness, where you get a serious sense of the grandness. There’s then the cultural backdrop of both the Caledonian Canal itself, and the various ruined castles and historical points you’ll pass too.

Typically, the route takes three days in a kayak, or five in a Canadian canoe. Some like to bring a sail for their canoe and try to make the most of those Scottish winds as they go. This is one of the great canoe routes in Europe, and is ideal for experienced solo travellers, though there are a variety of guides and group trips available to those with less experience.

Hike the Caledonian Canal: The Great Glen Way

Length: 79 miles (127km)

Days: 4-8 days

While there is definitely beauty to be found on the Great Glen Way hike and cycle routes, we really do believe that the best way to experience the route is by water, as when on foot (or bike), you can find yourself hidden from the view by the trees - and the Caledonian Canal is a concept with water at its very core. Still, the hike has its moments - and it is a route that is beloved by many long-distance hikers.

The hiking and cycling route follows the canal from Fort William to Gairlochy (10 miles/16km), following the back streets of Fort William out to River Lochy and on. You’ll then head to Laggan Locks (13 miles/21km) through beech and birch woodland and by Loch Lochy, to Fort Augustus (12 miles/19.5km). There is a choice to be made for this latter stage - either going via Invergarry or Laggan. From here, it’s on to Invermoriston (9.5 miles/15km).

Many hikers say that this route bursts into life from this stage onwards, with the high route here providing great views of Loch Ness. The next section takes you to Drumnadrochit (14.5 miles/23.5km) on another (relatively new) high route with yet more views of Ness. This section was specifically designed to get hikers away from the low forestry routes they used to follow.

Finally, it’s on to Inverness via a 20 mile (32.5km) slog, concluding the route.

Flora and Fauna

The Scots pine, birch and aspen of the Caledonian pine forest can be seen at times on this route, though a lot of the route is now forestry. The Great Glen Way passes through a lot of forestry plantations, usually non-native Sitka spices or Douglas firs grown for timber, and this is another reason why the canoe trail is typically more popular than the hiking or cycling routes.

In terms of the fauna, look out for red deer, roe deer, foxes, badgers, mountain hares and red squirrels on land. You’ll see a fair amount of Highland cattle too. In the skies, golden eagles have been known to venture into this territory, while in the waters you may spot Atlantic salmon, sea trout, brown trout or European eels - not to be confused with a certain mythical monster.

Inspired? Canoe the Great Glen Canoe Trail now!