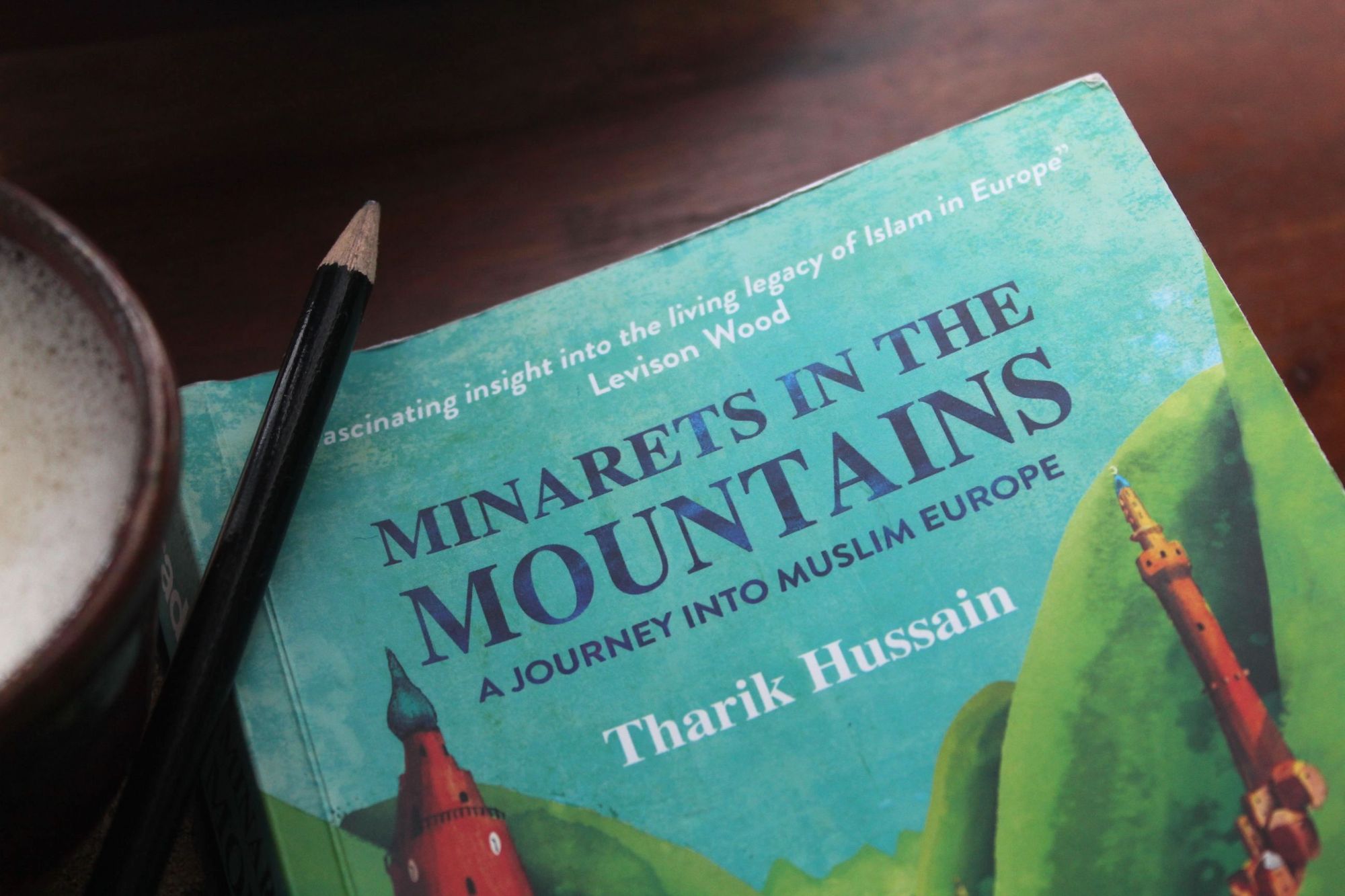

In Minarets in the Mountains, Tharik Hussain asks a simple question, but one which you don’t often hear asked: why is Europe’s Muslim history remembered so negatively, when it is remembered at all?

The travel writer quotes Bulgarian journalist Anthony Georgieff’s assertion that historians have gone to “great lengths” to “represent five centuries of Ottoman rule as nothing more than a ‘series of mass murders, impaling and rivers of blood’”, while “nothing was written about any of the fabulous architecture, the fascinating culture, tolerant society or liberal Ottoman sultans.”

Bulgaria is a nation whose words, food and proverbs - “even the habit of snacking on sunflower seeds” - can be traced back to centuries of Muslim rule. A chance encounter in Bulgaria opens Hussain’s eyes to the “living, indigenous Muslim Europe” which still exist today, and also “to how precarious its existence was and the efforts being made to eradicate and deny it,” he writes. “This left me overcome with a sudden and urgent desire to see what was still left.”

Minarets in the Mountains follows Tharik and his family as they visit the three countries in Europe with a majority Muslim population (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo and Albania), and their neighbours with centuries of Islamic history, Serbia, North Macedonia, Montenegro. Hussain also draws on the legendary 17th century Ottoman traveller Evliya Çelebi, a poetic primary source who visited many of the discussed areas during the Ottoman Empire.

Hussain has a contagious curiosity and such enthusiasm for the topic that, when combined with a healthy dose of historical detail, he is able to keep you engaged and entertained throughout. The book also has an unpretentious charm, mixing the facts with casual chats with locals, fellow tourists and family time, for those little moments of laughter and authenticity that really make travelling so special.

The themes of conflict and erasure follow Hussain around Europe, whether it’s the political history of Kosovo, the destruction of the Stari Most bridge during the Bosnian War or the controversial process of ‘Antiquisation’ in North Macedonia’s “Muslim Rome” of Skopje, where authorities are being accused by many of “trying to reinvent the country’s heritage” and ignoring the Slavic, Albanian and Muslim roots of the region (at great financial expense to the country).

The drive of this book is to focus on the indigenous Muslim communities, though. So, while conflicts are mentioned when important, there is more talk of the wonders, legends and historical achievements along the way - from the tomb of Murad I to a 550-year old tree in Skopje to the rebuilding of the Stari Most, and an explanation of why it's so important to Bosnia’s Muslim heritage.

There is cultural and natural beauty in abundance, from Podgorica’s Ottoman Old Town in Montenegro to fortresses in the rugged Albanian mountains to Sarajevo, one of Europe’s great cities, where coffee rules and the places of worship of various religions live happily side by side.

At its best, travel forces you to observe new and unknown things, and showcases the diversity and the variety of the world - opening us up as people. Great travel writing can achieve the same thing, transporting us to a new place through archaeology, literature, food and traditions - and adding another layer to our appreciation of the depths of human culture. Hussain achieves that here.

Inspired? Check out our range of adventure holidays in Kosovo, Albania and Montenegro now!

This article contains affiliate links. Which basically means we make a little commission if you click through and buy something. It doesn’t cost you anything, and it just means we can do more good things in good places.