The first recorded ascent of Ben Nevis was made by James Robertson, a botanist from Edinburgh, on 19 August 1771. Robertson had been sent to “make a botanical survey of the distant parts of Scotland” by a University of Edinburgh professor called John Hope, who was also the King’s Botanist and Superintendent of the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh.

Robertson was travelling at a time when Scotland, and particularly Edinburgh, was in the grips of the Enlightenment - the most famed participants of which included the philosopher David Hume and economist Adam Smith. John Hope too was a figure of this drive to advance societal knowledge, and in Robertson, he saw a “lad o’ pairts” who could be trusted to forward his ambitions of cataloguing the flora of Scotland and establishing a natural history museum in Edinburgh.

The summit far overtops all the surrounding hills, tho’ those towards the South & South East are very high...

Robertson’s first expedition for Hope came in 1767, when he left Edinburgh to tour the Western Isles and the West Coast of Scotland. He later journeyed to the Northern Isles in 1769 and 1770, visiting Orkney and Shetland, and in 1771, on 31 May, he notes:

“I set out from Edinburgh to continue my researches into the Highlands of Scotland. As I had formerly examined those places which border on the East, North & South coasts, I now directed my course thro’ the interior & mountain parts.”

That quest would be the one which took the 30-something scientist up the UK’s highest peak. In all probability, there will have been others who reached the summit of Ben Nevis in the centuries before Robertson, but the botanist was, at least, the first to record doing so - even if he didn't leave much evidence behind.

A Highland Endeavour

There is an obvious pull to climbing Ben Nevis, the highest mountain in Scotland and the UK, which stands 1,345m (4,4412m) high overlooking Fort William.

It is the same obvious pull that comes with climbing any peak which marks the high point of a country. Ben Nevis is not the tallest mountain in the world, but it is the tallest in Scotland - and to stand on top of it is to become the high point of the British mainland, however briefly, and to complete (by at least one, admittedly arbitrary metric) the most challenging ascent on the island.

James Robertson was an avid writer of reports and journals, scribbling constant notes as he travelled around the Highlands and Islands of Scotland from 1767-1771. His writing and reports have been gathered in the fascinating book A Naturalist in the Highlands: James Robertson, His Life and Travels in Scotland. Robertson’s diary entry for 19 August 1771 simply reads:

“I ascended Ben Nevis which is reckoned the highest mountain in Britain. The plants on this mountain seem similar to those on Ben Awin and Carngarm, only here, at the West side near the foot I found the M….. [word unfinished in entry]."

There is no talk of the struggles of climbing the country’s highest peak; no regaling of his heroics on the hill...

“The rock from top to bottom is a red Granite hardly distinguishable into strata. A third part of the hill towards the top is entirely naked, resembling a heap of stones thrown together confusedly. The summit far overtops all the surrounding hills, tho’ those towards the South & South East are very high, and are formed into Cones, or into a number of rugged peaks, or into long narrow ridges.”

There is no talk of the struggles of climbing the country’s highest peak; no regaling of his heroics on the hill, no boastful, dramatic monologue about being the first to ‘conquer’ this spot, which so many have climbed since.

Robertson's description of how the summit of Ben Nevis “far overtops all the surrounding hills” suggests that Robertson had fine weather on the mountain, yet there are no flowery descriptions of the surrounding peaks, of the views back down to Loch Eil or of the sheer, steep cliffs off the north side of Nevis.

The botanist climbed Ben Nevis for professional reasons - to observe and list the flora and fauna growing on the mountain; particularly at such a grand height, and his journal reflects exactly that. Still, his climbing effort should be commended. This was a time when ascending Ben Nevis was a lot trickier than it is today - and not just because he was lacking GoreTex hiking boots.

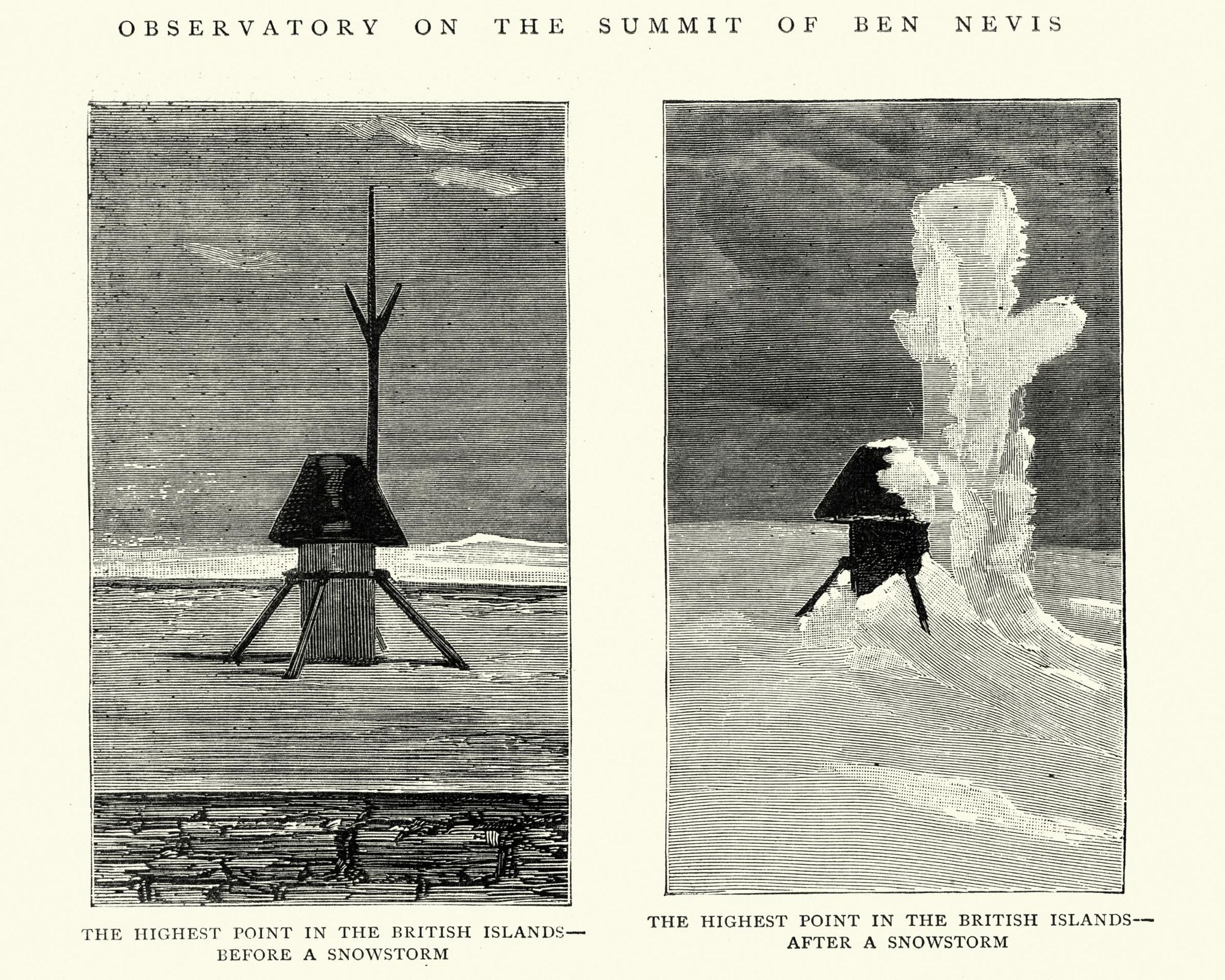

Robertson’s ascent in 1771 came a full 112 years before a pony track was opened on the mountain (to serve Britain’s only mountain-top observatory, which was operational on the summit of the mountain from 1883-1904, drawn below). It came 123 years before the West Highland Railway line opened in 1894 - so just getting to Fort William would have been a challenge for Robertson.

Perhaps it was the fact that Ben Nevis was not officially confirmed as the UK’s highest mountain when Robertson ascended it that led him to write such a blasé diary entry about the experience. It was suspected as such, though.

In 1654, the Blaeu Atlas of Scotland had been published by the Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu, and the maps show the highest mountain in the country as Bin Novesh (just imagine Sean Connery saying ‘Ben Nevis’).

The Welsh naturalist Thomas Pennant had also toured Scotland in 1769 and 1772 and wrote that “as an ancient Briton, I lament the disgrace of Snowdon; once esteemed the highest hill in the island, but now must yield the palm to a Caledonian mountain.” Pennant listed the height of Ben Nevis as 1450 yards, which translates to 1,325m and actually isn’t far off the correct 1,345m.

It wasn’t until 1847 that Ben Nevis was officially confirmed as the highest mountain in the UK - higher than not just Scafell Pike or Snowdon, but crucially, as higher than Ben Macdui in the Cairngorms - by the Ordnance Survey.

‘This Wild Expedition’

There could be another reason Robertson did not document the details of his ascent, of course. Maybe it was known to him, if not to us, that others had climbed Ben Nevis before him.

A man called John Drummond of Balhaldy had written in 1737 of: “a huge mountain, of prodigious hight, called Beniviss, at that time adorned with a variety of trees and bushes, and now with a beautiful green. Its ascent is pretty steep, though smooth.” He stated: “The top or summit is plain, covered with perpetual snow, and darkened with thick clouds.” Whether this implies Drummond knew some who’d climbed those slopes is up to interpretation.

What we know for certain is that James Robertson was not the first to attempt to reach the top of the mountain. Edward Burt, a rent collector in Scotland in the post-Jacobite era wrote of a summit attempt in 1754:

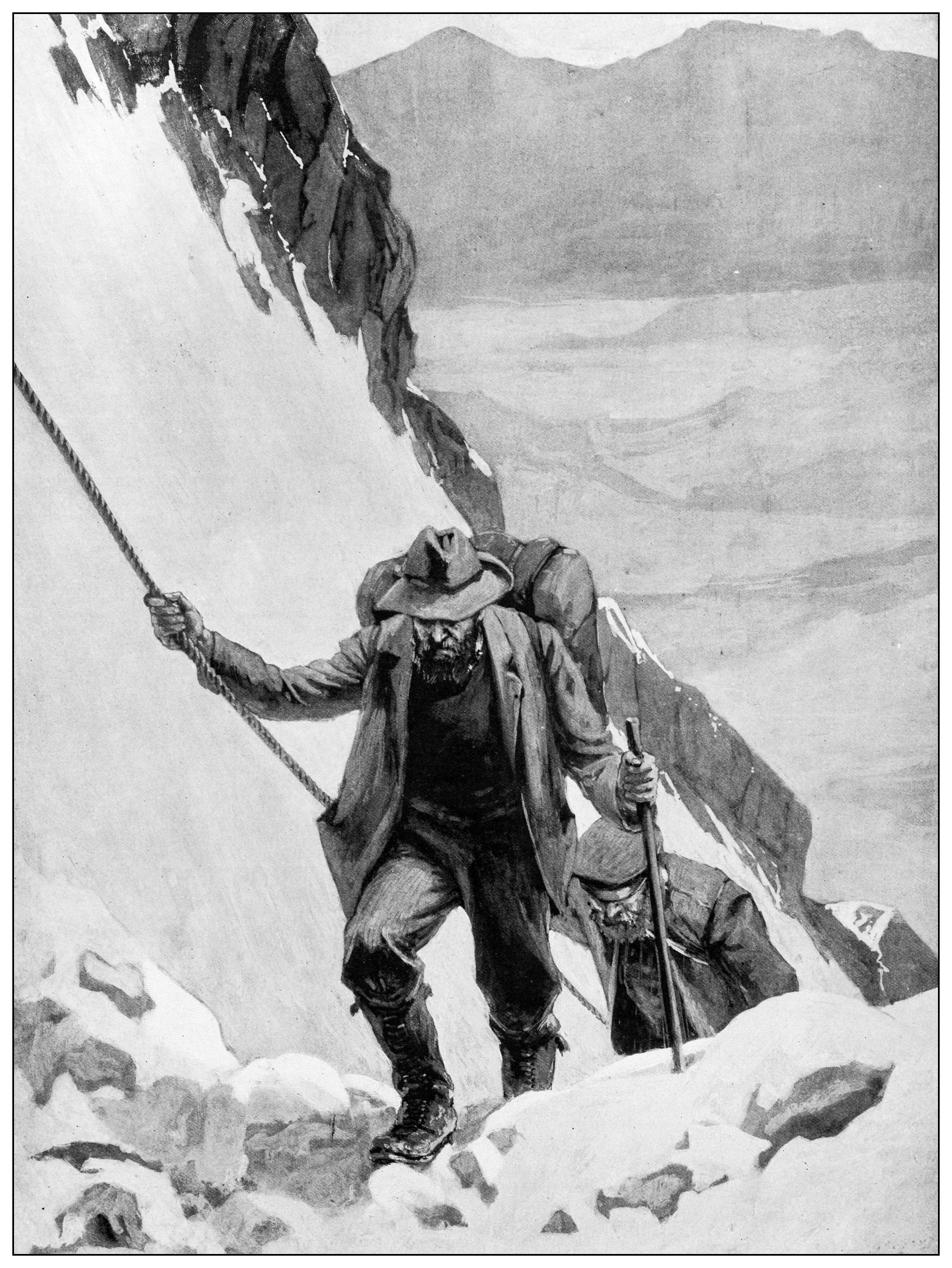

“Some English officers took it in their Fancy to go to the Top, but could not attain it for Bogs and huge Perpendicular Rocks,” he wrote, in his book The Letters from a Gentleman in the North of Scotland. “This wild Expedition, in ascending round and round the Hills; in finding accessible Places, helping one another up the Rocks, in Disappointments, and their returning to the Foot of the Mountain took them up a whole Summer’s Day from five in the morning.”

We know James Robertson was not the first to visit Ben Nevis for scientific purposes, either. There are reports of students from Edinburgh University scouring the mountain for medical ingredients in 1767. It's only four years later that we get that diary entry, modest and vague, from Robertson.

It’s worth noting that the societal perception of mountains was not positive in the 18th century.

Mountains were thought of as monstrous; a wild ‘other’ in a time when society was softening the natural world and scientific thought ruled over otherwise romantic notions. "Unproductive mountains had traditionally been regarded as physically unattractive," writes Keith Thomas in his book Man and the Natural World. "They were supposedly the home of uncivilised people."

The poet John Keats climbed The Ben in 1818 with a local guide. Keats walked much of the route to the summit in mist - sipping whisky en route...

Maybe this was why Robertson didn’t write more about Ben Nevis. But it does seem difficult to believe that a man so devoted to exploration and botany could not have had an appreciation also for the beauty of such mountains. Just a week before ascending Ben Nevis, Robertson described visiting “a remarkable cascade called the fall of Fires [which] strikes a spectator with solemn pleasure.” It seems he simply kept his less scientific thoughts on ‘The Ben’ to himself.

After Robertson, reports of climbing Ben Nevis become more common.

A Welshman called John Williams made the ascent in 1774. By the 1780s, groups were taking on the climb with early mountaineering equipment. The poet John Keats climbed The Ben in 1818 with a local guide. Keats walked much of the route in mist - sipping whisky en route - which is an experience which will no doubt resonate with many who have climbed the mountain in the modern day.

As the 1800s progressed, climbing clubs sprung up in cities around Scotland, and in 1889, the Scottish Mountaineering Club (SMC) was formed in Glasgow. Today, around 130,000 people climb Ben Nevis each year - most via the Mountain Track, though the more intrepid arrive via the Càrn Mòr Dearg Arête, or even by popping their head over a cliff edge, amazing tourists.

No such crowds would have awaited Robertson at the summit in August 1771.

Sources:

- A Naturalist in the Highlands: James Robertson, His Life and Travels in Scotland - edited by D.M. Henderson, J.H. Dickson

- Ben Nevis: Britain’s Highest Mountain - Ken Crocket and Simon Richardson

- Man and the Natural World: Changing Attitudes in England 1500-1800 - Keith Thomas

Inspired? Check our our winter climbing skills trip on Ben Nevis now!